‘We have to fight’: Europe’s carmakers dig in against China’s EV incursion

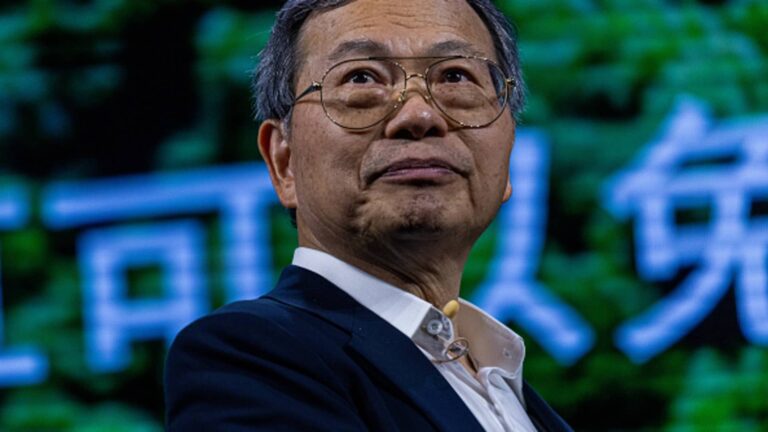

This was Brian Gu’s first ever Munich motor show, but the vice-chair of the Chinese EV maker Xpeng still saw a lot of familiar faces from home.

“They’re all here,” he said, naming Chinese rivals from Warren Buffett-backed BYD to Geely.

Twice as many Chinese carmakers exhibited at Europe’s largest biennial motor show this year compared to 2021, occupying almost two-thirds of the floor space.

Many used the show to unveil a bevy of enticing new models intended to win European motorists over from the German brands that historically dominated the exhibition.

Xpeng, which recently agreed a €5bn deal to help Europe’s largest carmaker Volkswagen improve its technology, used the Munich event to reveal that it would from next year start selling cars in Germany, France and the UK.

For years, China’s carmakers learned their craft from western rivals, through joint ventures that the international auto groups were required to form.

At the same time, China placed significant bets that batteries would dominate technologies needed to decarbonise road transport, and particularly the 90mn cars sold worldwide every year.

Now, with a fast-growing EV market and a wealthy, car-loving population, Europe has become the largest crucible of battery car activity outside of China, and a leading target for the country’s carmakers.

As a ban on petrol or diesel car sales by 2035 looms, the Chinese see an opportunity to capture market share by offering models with advanced technology and world-leading batteries at low prices.

“It is always a big threat when other people catch up,” said Thomas Ingenlath, CEO of EV brand Polestar, which is majority owned by Volvo Cars and Li Shufu, owner of Volvo’s parent Geely.

“Other countries . . . have found an edge to technology which [legacy carmakers] might have ignored for too long,” he adds. “The question is always how fast can you react?”

Now, after months of fruitless lobbying of politicians to block or deter Chinese imports, the region’s carmakers are preparing to face down their newest rivals.

“We have to fight,” says Uwe Hochgeschurtz, European operations chief at Stellantis, the region’s second-largest carmaker.

“We must be very careful because when you have a new technology, somebody who has already invested for some time in this technology, there is probably a lack of competitiveness,” he says. “That’s dangerous, and we have to fight and to make sure that we are coming back to a competitive situation.”

Stellantis has cost advantages from making Fiat, Peugeot and Vauxhall cars using one system, he says, while its array of nameplates that include Alfa Romeo and Jeep are widely known.

“Everybody knows our brands, you do not have to create something which has a strange name in it.”

Yet illustrious logos may not be enough to stave off the new entrants, as the steady rise of Tesla has demonstrated.

Prospects of a price war one of the main talking points at the Munich event as executives toyed with possible implications of the coming wave.

“If your profitability overall is higher than most of your competitors, you can follow longer than the others,” says Hochgeschurtz, who pointed out that Stellantis was the most profitable of its rivals. “So you are better prepared for a price war.”

The company is even considering manufacturing EVs in cheaper regions outside of Europe, and importing them in.

“We have some capacity in some other countries close to Europe,” he said, and would consider any plan “if it makes business sense”.

Renault’s chief executive Luca de Meo said while prices needed to come down, there were differences in vehicle specifications.

The often-made comparison between the low-price Chinese MG 4 and Renault’s electric Megane focuses on the €10k difference, but the French model has a higher-grade battery, better infotainment and installed Google services, he says. “It’s a different car.”

“Of course we need to make electric cars cheaper, they are too expensive,” de Mayo said, adding: “But not everybody is looking for the cheapest product in the market.”

The Chinese are acutely aware of the fertile ground to be found in lower price brackets.

“Many European consumers cannot afford the current electric vehicles,” said LeapMotor founder Matt Lei, who helped relaunch the MG brand as an electric nameplate. He said he was “shocked” at how prices across the continent had risen since he lived in the region. “We have to beat on price.”

Yet Europe has one of the highest-priced cars in the world and is home to the greatest density of premium or luxury brands, stretching from Sweden’s Volvo to Britain’s Range Rover, Germany’s Mercedes, Audi and BMW and Italy’s Masserati.

Price is “clearly much more of a challenge in the low price spectrum than in the premium and luxury segments where we operate”, says Polestar’s Ingenlath.

“I am not so much afraid of the price position, I’m much more afraid of the kind of technology they bring, whether they are somewhere ahead of us that is unreachable. That would be frightening.”

Yet on technology too, the Chinese are quietly confident.

“Technologically, I think we are quite, quite the best,” says Xpeng’s Gu. “Also on the cost areas, the scale, in manufacturing, the supply chain and everything that can give us the confidence that we can build something competitive.”

Not all the Chinese brands are brimming with ambition, and many are realistic about the challenges of breaking into the auto world’s most competitive arena.

“I would rather say the biggest challenge for us at this moment is not how successful we are by 2030,” said Lei. “Instead, we need to find our way to survive here.”

“The customer’s expectation is very high. So for me, at this moment, I have to do everything correctly in order to please my customers, so that they can recognise this brand and I can survive. So I believe that is the ultimate goal for me.”

Many executives that it will take years for any significant market share to be taken, while Europe’s own players are racing to improve their vehicles to meet the challenge.

“We should not underestimate their might and competence, and the customer loyalty,” says Sigrid de Vries, head of ACEA, the European industry’s trade body. “The industry is too easy to talk down.”