Receive free Investing in funds updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Investing in funds news every morning.

Ed Moisson is a journalist at Ignites Europe and the author of The Economics of Fund Management.

Fund managers are constantly criticised for underperforming while charging inflated fees. So linking fees to their performance sounds pretty appealing, right?

In principle, a performance fee aligns an investor’s interests with those of the fund manager — higher returns for the client result in higher fees for the manager. Performance fees are best known through their use by hedge funds, where investors rarely have a choice but to pay these fees on top of asset-based management fees.

But how popular are performance fees with mutual fund investors, where there is plenty of room to avoid the fees if investors want? It’s a bit of a mixed bag, but on the whole they remain (surprisingly?) unpopular.

In the US, hedge fund-style performance fees are banned for mutual (‘40 Act) funds. Instead, fulcrum-style fees are allowed, which are paid when returns are on the up, but also cut back when a fund underperforms. This structure overcomes a flaw in traditional performance fees, which are only charged one way — the classic “heads I win, tails you lose”.

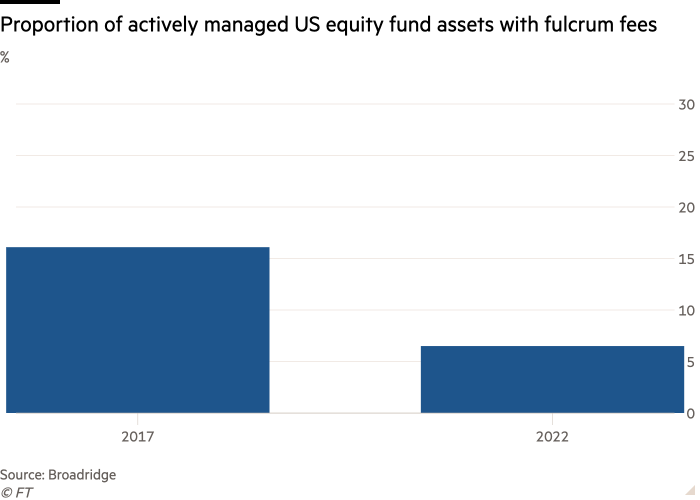

However, the use of fulcrum fees is actually falling in the US. Among actively-managed equity funds only 6.5 per cent of fund assets have fulcrum fees in place. That’s down from 16 per cent five years ago, according to data from Broadridge.

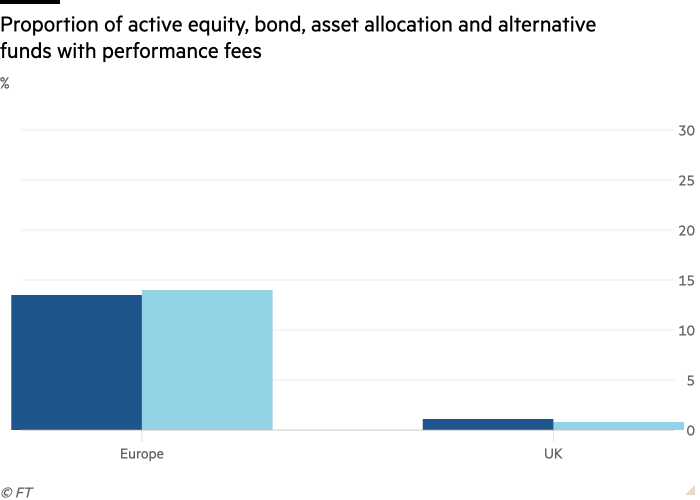

In Europe charging a hedge fund-style performance fee is allowed — and some do. Performance fee structures are in place for about 14 per cent of assets under management across asset classes, according to Morningstar data. But that’s only up from 13.5 per cent five years ago. (The rise would admittedly have been stronger if alternative investment strategies — where almost half have performance fees — hadn’t shrunk over the same period).

Performance fees in the UK haven’t really taken off either since they were first allowed for domestic funds in 2004. In fact, they’re on the wane from a low base. UK-based fund assets where performance fees are in place have dropped from just over 1 per cent to just below that level over the past five years, Morningstar data shows.

But why? If performance fees are theoretically alluring, why do investors seem in practice to shun them?

It’s safe to say that the situation in the UK is largely thanks to independent financial advisers like Hargreaves Lansdown never having warmed to performance fees. The somewhat greater openness to performance fees in continental Europe is probably partly because distribution is dominated by banks and insurers, which often have in-house asset management arms and, well, tend not to be as sensitive to funds’ fee levels.

Banks are important fund distributors in the US as well, but regulations governing the payment of commissions to intermediaries are more similar to the UK than the EU. The willingness (or unwillingness) of intermediaries to use funds with performance fees seems to follow a similar tack. In other words, intermediaries care less about performance fees when they are not incentivised to keep a lid on costs borne by clients.

It’s worth remembering that performance fees are used for actively managed funds, which attract clients primarily based on their perceived ability to deliver outperformance (often swayed by their record of achieving this in the past). However, on average, funds with performance fees don’t seem to have better performance — which obviously doesn’t help their ability to attract more clients.

Another factor that helps explain why performance fees have failed to gain more traction is simply complexity.

Firstly, financial intermediaries with fee budgets can find performance fees fiddly to manage. Secondly, performance fees are trickier to explain to retail clients, so independent advisers and wealth managers are often inclined to avoid them.

For example, back in 2018 two Fidelity-managed investment trusts explicitly turned down the opportunity to use the asset manager’s variable management fee model because of complexity (they instead chose to reduce management fees as assets rise).

There are still some solid reasons for performance-related fees. High on the list is the structure’s potential to dissuade asset managers from letting a fund grow too big. As even Warren Buffett has repeatedly groused, size is the enemy of returns. But any arguments in their favour surely only stand up to scrutiny if asset managers try to balance the interests of investors with those of fund managers.

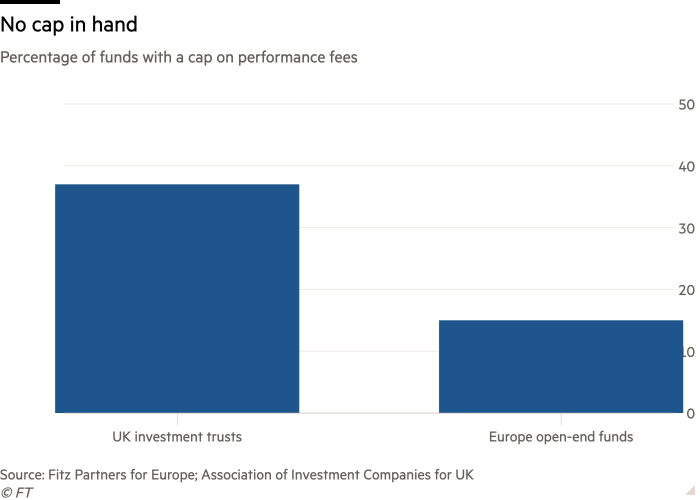

One basic element for setting up a fair performance fee is a cap on the revenues that can be generated. The recent excesses at Jupiter-managed Chrysalis Investments shows the problems if a cap is missing.

Sadly, most funds make little effort to bother with this. In a study of more than 1,000 European funds with performance fees, research firm Fitz Partners last year found that only 15 per cent had a cap in place. UK investment trusts fare a little better, with the Association of Investment Companies finding that 37 per cent cap performance pay-offs.

This seems to be the problem with many performance fees. The principle sounds great but the execution is not. Investors who have a choice seem to have spotted this and are voting with their feet.