Receive free UK economy updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest UK economy news every morning.

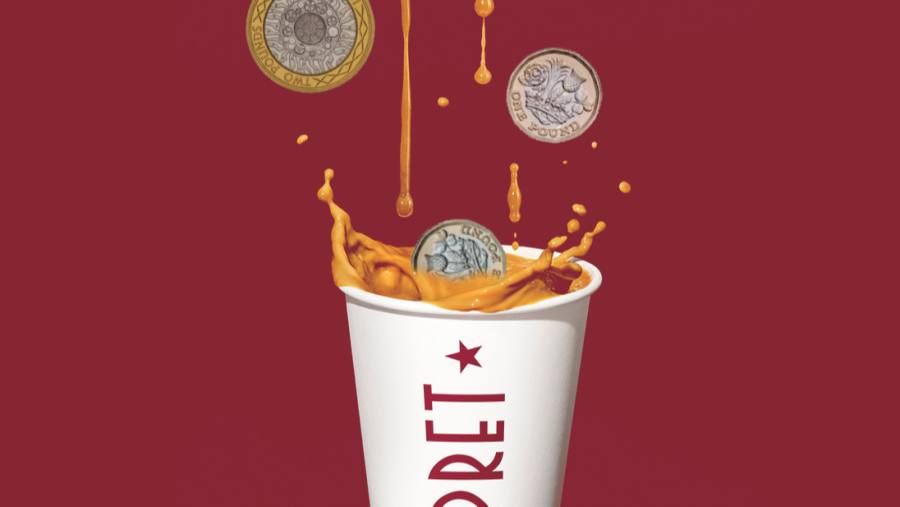

Bloomberg last week ran an interesting interview with Pret a Manger CEO Pano Christou.

Pret is a measure of economic activity as well as a sandwich shop. For the past few years, Pret has been giving sales data to Bloomberg for a realtime index that claims to track activity in financial districts, transport hubs and shopping centres. The Bloomberg Pret Index — also published by the ONS — uses as its baseline the weekly transaction average from the first four weeks of 2020.

The index currently suggests City of London footfall is flat-ish year on year, at about 80 per cent of the pre-Covid average, which is the slowest recovery out of all the regions measured. This, says Christou, reflects the new normal of office workers turning up three days a week:

Till roll volumes might not tell the whole story, however. Because, as any Pret customer will attest, the sandwiches have become bloody expensive. Per Bloomberg:

Pret’s bestseller, a tuna and cucumber baguette, has risen from £2.99 in December 2021 to £4.25 today — an increase of 42%. The price of a chicken Caesar and bacon baguette has jumped about 32% from £3.99 to £5.25 . . .

According to Christou, the above-inflation price rises are due to mounting energy costs — up 300% this year — higher wages, and the increased cost of raw materials. Pret’s salmon supplier lifted prices by about 50% while a crisp supplier hiked them by 100%. Staff, whose annual pay is already up 20%, are likely to receive another increase this year.

Does this explanation wash? For science, we scraped three years of prices from Pret’s delivery ordering portal via Wayback Machine. Here are the price ranges for each product, going backwards through time:

Note that the data points shown here are only when the menu page was cached, not when it changed. Note also that prices online are slightly higher than the regular in-store prices, and that products might not remain identical over the whole period sampled. Still water is a 500ml bottle before October 2022 and 750ml thereafter, for example, but it’s included in our dataset because it’s still water.

Here’s what the data looks like over time by category and individual product. Use the dropdown menus to pick your favourites:

And here’s the price data rebased to 100 as of August 2020 (except for the humous and chicken pesto wraps, which have no pricing data available before November 2020 and April 2021 respectively). There’s a series selector to aid comparisons:

Against early-pandemic levels, Pret sandwiches and baguettes are more expensive by approximately 50 to 75 per cent. Drinks, fruit and brownies have nearly doubled in price.

From 2020 to June 2023, cumulative UK CPI inflation was 20 per cent.

Christou told Bloomberg that Pret remains competitive, a claim that needs context not found in the data. In January the chain launched a cheaper range of “Made Simple” sandwiches, which are not always made obvious to habit purchasers in prime locations like the City. A £5 baguette-plus-crisps offer was announced at the same time but disappeared after just a month.

As is stands, an online-ordered Pret ham sandwich, brownie and Coke was £5.55 in 2020, £6.80 last May, and £9.90 today. Meanwhile, according to the 2023 Lumina Intelligence UK Food To Go Market Report, the majority of supermarket and cafe-chain meal deal prices remained unchanged last year. The table below is based on our own research using sources including Essex Live’s 2019 meal deal review:

Does all this have a point? Sort of.

The Pret Index is cited by the ONS and by real estate, retail and tourism analysts as a realtime indicator of footfall. But it’s a volume measure, so works well if only sandwich prices are stable or demand is price inelastic. The former definitely isn’t true and the latter probably isn’t either.

Pret’s recent pricing strategy strongly suggests that it’s been prioritising margin over volume. Transaction levels might therefore be overestimating areas where there’s no alternative (airports, shopping malls, Yorkshire), while underestimating the workday population in places like the City, where convenience food is plentiful and there’s an established pre-pandemic memory of what a tuna baguette should cost.

A further possibility, that white-collar workers are encouraged to work from home because the lunch that once cost ~£5 now costs ~£10, is also worth considering. Whichever way, hyper-Pretflation means the chain’s usefulness as a realtime consumer indicator may have passed its use-by date.

Further reading

— How much does a pint of lager cost? An Alphaville investigation (FTAV)

— Inflation hits London barber shops with the £10-plus haircut (FTAV)