This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Taco Bell, we learned yesterday, is facing a class-action suit for allegedly misrepresenting the volume of fillings in their Crunchwrap and Mexican Pizza products. We tend to think the accusations are true, but still place Taco Bell high in the fast-food league table. May the court temper justice with mercy! Meanwhile, send us your fast food preferences (but if you think KFC is better than Popeye’s you can just cancel your subscription): [email protected] & [email protected].

SoFi is confusing

SoFi is a fintech company which, among other things, originates personal and student loans, takes deposits and issues credit cards. Its shares rose 20 per cent yesterday after the company reported earnings, and the stock has more than doubled since the end of May.

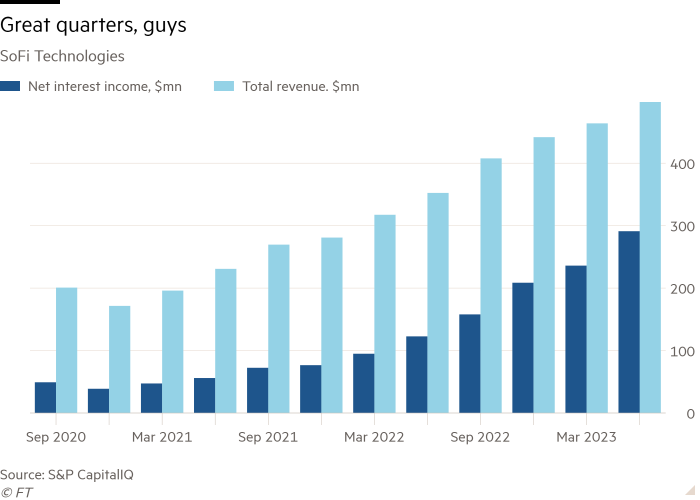

The business is growing fast. Loan origination rose 37 per cent in the second quarter from the year-ago period; net interest income more than doubled. Deposits rose 27 per cent. Here is what total revenue and net interest income look like over the past 12 quarters:

The elevator pitch for SoFi, as I understand it, is that they are better at originating certain kinds of loans than the banks it competes with; it sells a lot of those loans on to banks or securitises them, which keeps the balance sheet tight; and now they are building a deposit franchise and various fee-generating bells and whistles on top of the origination business. The business model seems to be working, if the growth is any indication (though with any lender, especially young ones, investors are always holding their breath until the next low in the credit cycle has passed).

I’m not going to assess the fundamental virtues of SoFi’s business here. Instead I’m going to complain about how it presents its results.

Looking at the financial statements, it looks to me like SoFi is simply a bank. I don’t mean this in the official or technical sense, though SoFi did become a bank holding company last year. I just mean that it’s a balance sheet business, and a spread business. Fundamentally, it buys capital on the liability side of the balance sheet, and sells the capital on the asset side of the balance sheet, with the goal of selling the capital at a higher price than it paid. With banks, we think about growth in terms of growing equity (“book”) value, about return on equity, and about net interest margin. We look, in short, at the balance sheet.

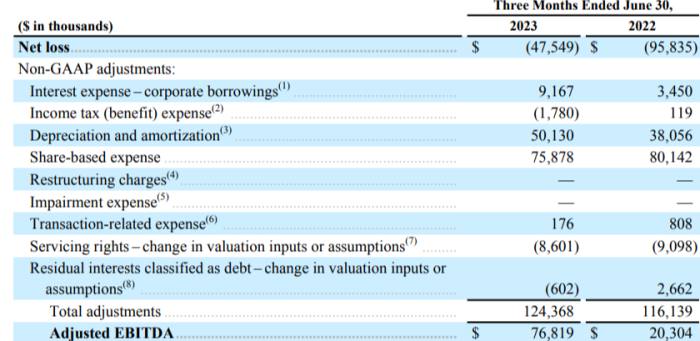

SoFi does disclose net interest margin (which expanded nicely last quarter). But, tellingly, NIM first appears on page 18 of the quarterly presentation. The group wants investors to think of it as a technology company, and for technology companies, the income statement is the thing. So SoFi wants us to measure profitability in terms of “adjusted ebitda”. Here is how they calculate it:

We have shown in this space before that adding back stock expense to adjusted earnings is always and everywhere wrong and deceptive. So I will merely note here that without the (awful) stock-comp adjustment, SoFi barely broke even on an ebitda basis last quarter. But what really raises my hackles in this case — and it’s not even that big an adjustment — is that SoFi adds back interest on corporate borrowings. The company’s justification: “Our adjusted ebitda measure adjusts for corporate borrowing-based interest expense, as these expenses are a function of our capital structure.” But if you are a bank, you are your capital structure.

SoFi might argue, in response to my complaint, that only half its revenue comes from net interest income. But the same is true of JPMorgan, which, I can say with confidence, is a bank — despite having a staggering tech budget and lots of fee income. Yes, SoFi sells many of the loans it originates. But so does JPM. Using technology to do business does not make a company into a tech business. Tech businesses mainly sell technology. SoFi mainly sells money, no matter how many times it uses the word “platform” (20 times in yesterday’s call with analysts, by my count).

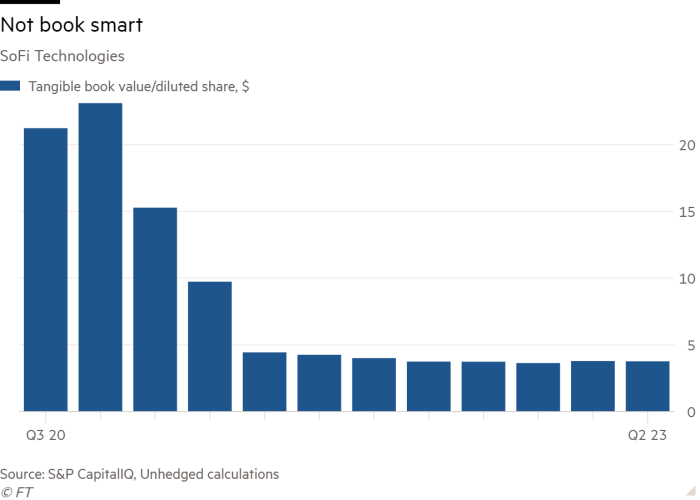

One reason SoFi might not want to encourage investors to think in terms of returns on equity is it does not make a net profit — and some version of net profit must serve as the numerator in any respectable return on equity calculation. Similarly, looking at the evolution of the company’s tangible book value per share, the picture is not pretty, because of very heavy share dilution in the past few years driven by acquisitions and going public as a Spac.

It is a bad idea to present a fast-growing but still unprofitable bank as an adjusted-ebitda-profitable tech company. It makes it hard to see how the business is really doing.

The BoJ is tightening on its own time

The Bank of Japan doesn’t mind leaving investors dazed and confused. That’s how many felt last week, after the central bank fiddled with yield curve control, its cap on 10-year bond yields. The FT’s crack Japan news team called it “opaque”.

Recall how YCC works. The BoJ sets a trading range for 10-year Japanese government bonds (until Friday, at plus-or-minus 0.5 per cent). If yields break out of the range, the bank hammers the market back into submission with bond buying. The hope is that a credible commitment to YCC won’t need much defending — that bond traders won’t start a fight they cannot win.

YCC’s mechanics are plain enough. What the bank did Friday is hazier. The hard-limit trading range has been widened, from 0.5 per cent to 1 per cent; any moves above 1 per cent will be squashed as usual. But 0.5 per cent remains the “reference” point. Between 0.5 and 1 per cent, the bank will “nimbly” steer the 10-year yield, at its discretion.

On Monday, as 10-year yields crossed 0.6 per cent, the BoJ nimbly stomped on them, pledging to buy the equivalent of $2bn in JGBs. This is surprising. Many analysts figured the central bank was giving itself a looser target to defend in order to buy fewer JGBs. And yields, at 0.6 per cent, were well below the hard cap.

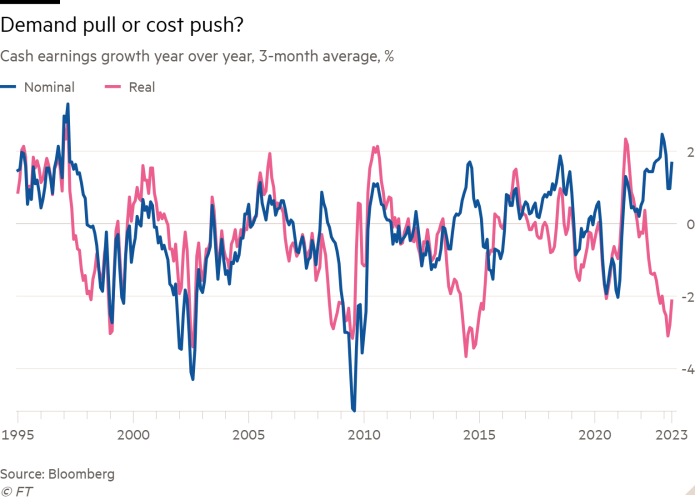

What’s going on? Start with the big picture. Tighter policy makes sense if inflation is durably in place. And inflation expectations are rising, as are the BoJ’s own inflation forecasts. Headline, core and supercore inflation are all high-three to low-four per cent range, with price increases happening across a broad range of items. But there is one big hole in the inflation story. The chart below shows Japanese wage growth. Nominal wage growth is elevated — but not by much. Crucially, though, real wages are shrinking:

Without ingrained wage growth supporting consumption demand, can inflation last? The central bank isn’t sure. The YCC tweak, then, is best seen as a prelude to monetary tightening, without constraining the BoJ’s options should inflation prove transitory.

This is, in one sense, a small change. Corpay’s Karl Schamotta points out Japanese yields remain puny by global standards, maintaining pressure on the yen. The BoJ’s longer-term goal may be to slowly water down YCC without any sudden changes, says Michael Metcalfe of State Street Global Markets. They’ve done something similar before. YCC’s introduction in 2016 made moot the central bank’s ¥80tn annual commitment to JGB purchases. Yet the pledge stayed officially in effect until 2020, for fear of signalling unhelpful policy tightening.

However small the change, it is tricky to manage yields upward without inflicting sudden losses on bondholders. Thus yesterday’s intervention. As Joseph Wang, the Fed Guy, writes:

The BoJ’s iron grip on their bond market will help investors adjust to losses in a measured manner. A move from 0.5% to 1% in 10-year JGBs implies a decline in market price of around 5%, which is painful but limited and foreseeable. This would allow investors to adequately prepare and makes disorderly moves like those seen in the UK gilt market in 2022 unlikely. Any further tweaks to YCC would also very likely be gradual and well anticipated.

How will the YCC tweak matter for global investors? Robin Wigglesworth has covered this in some detail over at Alphaville (his conclusion: maybe a bit, but not much). We won’t rehash his piece, but one additional asset class bears mentioning: Japanese equities, where this year’s 20 per cent rally has been driven disproportionately by foreign inflows. For the rally to power higher, global asset managers need to increase the size of their Japan allocations, which are tiny. If global investors read the YCC tweak as one more sign that the deflationary era is ending, that will be good for stocks. (Ethan Wu)

One good read

Bad things happen.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here

The Lex Newsletter — Lex is the FT’s incisive daily column on investment. Sign up for our newsletter on local and global trends from expert writers in four great financial centres. Sign up here