Receive free Kering SA updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Kering SA news every morning.

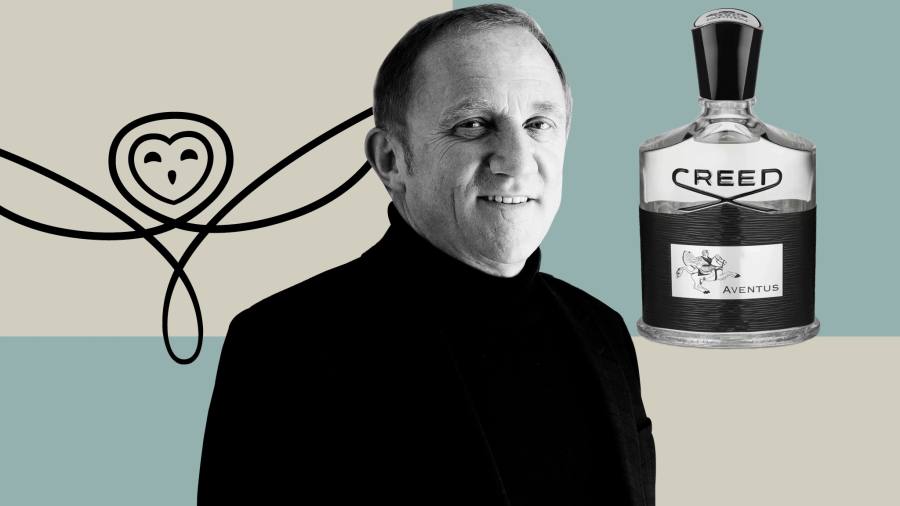

French luxury group Kering paid €3.5bn to acquire the fragrance brand Creed as the Gucci owner embarks on a strategically important expansion into the competitive high-end beauty sector.

The Paris-based group did not disclose the terms of the deal unveiled last month for Creed, whose colognes were worn by royals including King George III, but four people familiar with the matter provided details to the Financial Times.

It is the latest sign of the valuations that buyers of luxury beauty brands are willing to pay. Earlier this year, L’Oréal snapped up minimalist soap maker Aesop in a $2.5bn deal.

Two of the people said that part of the reason the details of the transaction were not provided was that the companies did not want to broadcast Creed’s steep profit margins.

Kering said Creed had sales of more than €250mn in the year to the end of March. Two people said Creed’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation were about €150mn, giving it margins above 50 per cent. That equates to an ebitda multiple for the acquisition of about 23 times, which analysts said reflected Creed’s brand strength and the scarcity of targets available in the high-end beauty industry.

Kering declined to comment.

Founded in 1760 in London by James Henry Creed as a tailoring house working for Europe’s royal families, Creed eventually became a fragrance company and moved to Paris in 1854 at the request of Napoleon III. The boutique specialises in high-end perfumery and is best known for its men’s fragrance Aventus.

The asset manager BlackRock took a majority stake in Creed in 2020 through its Long Term Private Capital fund. The deal was orchestrated by Javier Ferrán, chair of consumer company Diageo and International Airlines Group, who also invested personally and became chair of Creed, according to some of the people.

Kering’s deal for Creed was “a big price” and probably a premium on some other recent transactions, said Thomas Chauvet, a luxury goods analyst at Citi.

He noted that the brand has a lot of potential to branch from its current focus on men’s fragrance into women’s lines and skincare. “It’s expensive . . . but it gives them credibility that their ambitions in beauty are serious,” Chauvet said.

The move also reflects how Kering, which is backed by the billionaire Pinault family, sees expanding into beauty as a priority. Kering has been plagued by more sluggish growth compared with larger rivals such as LVMH and Hermès in recent years, and investors have questioned if it is too reliant on Gucci, its biggest brand.

Kering is one of the world’s biggest luxury groups with €20.4bn in revenues last year and a stable of brands that include Saint Laurent and Pomellato.

Although Kering has sought acquisitions in the past, including failed talks with Swiss group Richemont, there are few suitable targets in luxury fashion or leather goods. This has prompted Kering to focus on beauty as a key growth area, said a person familiar with the matter.

Kering announced in February that it would create a new beauty division to develop cosmetics and perfumes for its fashion brands including Bottega Veneta and Alexander McQueen. It also hired a high-profile executive from beauty powerhouse Estée Lauder to run the unit.

Analysts and industry experts estimate multiples for transactions in the beauty sector have run at about 22 to 23 times ebitda. Beauty and perfume sales bounced back and grew rapidly after the pandemic, and have proved resilient despite recent high inflation.