Receive free Technology sector updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Technology sector news every morning.

If you want to sound knowledgeable around investment types, nonchalantly mention “the cycle”. This can refer to a couple of things other than a pedal-powered, carbon-fibre expression of a midlife crisis.

The first is the business cycle within a sector. An example from manufacturing would be openings of new factories that push down surging prices.

The second is the broader boom and bust of the economy, characterised by rising and falling growth. The profits of many companies are highly connected to this.

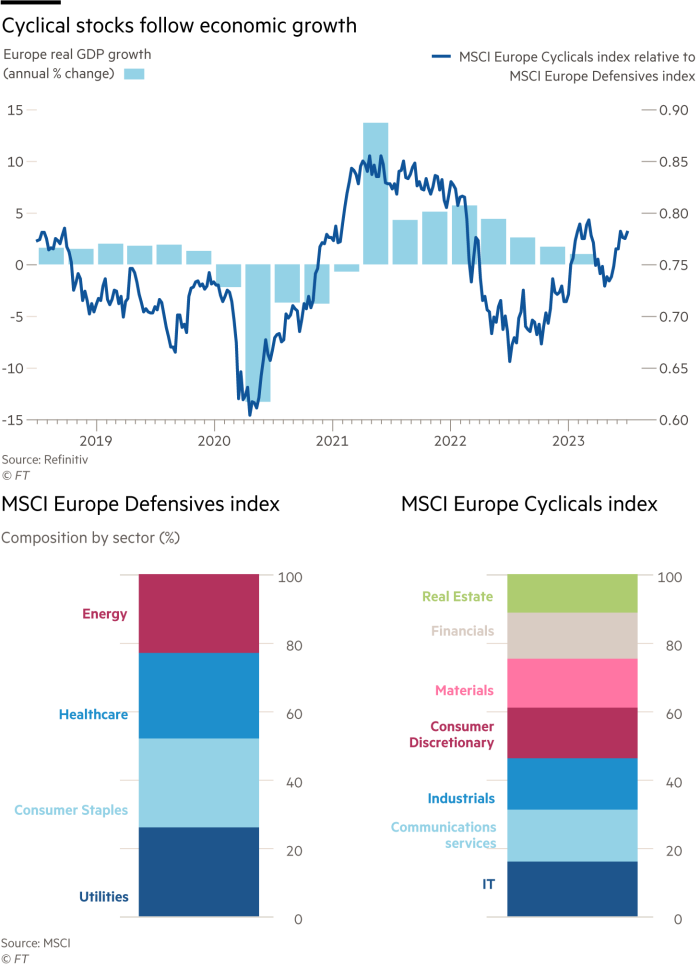

With Europe in recession, that kind of cyclicality is back in focus. It puts a premium on so-called “defensives”. These businesses have some insulation from the economic cycle, usually because they sell products or services most customers are unwilling to economise on, such as groceries or cigarettes.

Profit warnings from cyclical companies are a feature of downturns. On the continent, chemical groups are a source of concern. Recent warnings from Germany’s Lanxess followed reports of slowing demand from giant BASF earlier in the year. Both companies pointed to the lacklustre recovery in China as a source of weakness.

Cardboard and paper makers have joined the slump as demand for packaging falls. They benefited from a surge in online shopping during the pandemic. This effect is now fading, exacerbating the decline in earnings.

European cyclical stocks as measured by MSCI indices have nonetheless outperformed defensive counterparts since last year. Economic performance has been better than pessimistic forecasts in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. With stresses building in the economy, defensive stocks may now outperform.

In the UK, with its limited roster of quoted manufacturers, cyclicality is most observable among housebuilders. These have been warning of lower volumes and falling home prices for more than a year. Builders and materials groups have been in the same boat. The sector is reliant on investment and credit. Both are becoming scarcer as interest rates rise.

Insulation and roofing specialist SIG was the latest to chip in this week; faltering demand means profits will be at the lower end of expectations this year. Shares fell steeply. Housebuilders and materials groups have dropped by about half since the start of 2022.

Some investors attempt to switch back and forth between cyclicals and defensives as the economic outlook wanes or waxes. Others try to transcend cycles by investing in technology companies which, according to the jargon, have “secular growth stories”. These businesses hope to grow much faster than economies, thanks to innovation.

Cyclicals and defensives tend to be mature businesses. It is reasonable to value these on earnings predicted for a year or two in the future. It is a category error to value new technology businesses in this way, as some Lex writers did when initially confronted with the likes of Amazon, Facebook and Tesla. Share prices of fast-growing business will always appear exorbitant measured by next year’s forecast earnings.

These stocks are sometimes described as “binary plays”: they will either change the world or they will not. Old school City stockbrokers preferred the term “death or glory shares”, in homage to the motto of a British cavalry regiment.

Investors have to judge whether death or glory awaits the hopeful startup. You cannot dispel the high level of uncertainty with fusty calculations. No one’s figures are likely to be right a few years down the line.

Finally, a qualification. Tech stocks last year proved they can have a cyclicality all of their own. Prices slumped because risk-free investment returns had increased. Of late they have rallied, driven by enthusiasm for artificial intelligence, suggesting they can once again transcend the economic cycle.

J Sainsbury: sweet Nectar

A pioneering rewards card allowed Tesco to overtake rival J Sainsbury nearly 30 years ago. This week it was the latter’s turn to credit a loyalty scheme for rising market share. Simon Roberts, chief executive of the UK supermarket group, said its recent “Nectar Prices” initiative helped fuel a return to volume growth last quarter.

Critics accuse supermarkets of using inflation as an excuse to charge higher prices. A shrewder suspicion is that the cost of living crisis makes it easier for store chains to harvest data via loyalty schemes.

Nectar offers eye-catching savings. A jar of Nescafé Gold Blend instant coffee is less than half price, for instance. That may be infuriating for those who dislike sharing data. But Nectar users have swollen by nearly a tenth since April.

Tailored ad sales via its app are one benefit. It expects Nectar 360, its digital advertising arm, to bring in an additional £90mn profit in the five years to 2026.

The data also supports tailored promotions. Algorithms decide the generosity of the discounts based on a customer’s potential value. The offers on up to 10 items a week can amount to as much as £200 a year.

Sainsbury’s operating profit margins of 3.3 per cent are slightly below pre-pandemic levels. That partly reflects recent price increases that were 0.9 percentage points lower than the sector average, according to UBS. The likes of Aldi, which eschews a loyalty scheme in favour of across-the-board discounts, are still cheaper than Sainsbury’s. But the gap is narrowing.

Sainsbury’s is regaining its competitive edge. Its shares are up a fifth this year, more than twice as much as Tesco. The stock is priced at 13 times forward earnings, a tenth higher than its 10-year average.

Investors fret — and shoppers dream — of a grocery price war. But personalised loyalty card discounts make price comparison harder. The success of loyalty schemes means a sector-wide food fight is less likely.

Our popular newsletter for premium subscribers is published twice weekly. On Wednesday we analyse a hot topic from a world financial centre. On Friday we dissect the week’s big themes. Please sign up here.