Receive free Waste management & recycling updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Waste management & recycling news every morning.

Even in a country that bristles with architectural curiosities, bizarre artistic experiments and exuberant public projects, the Maishima rubbish incinerator stands out — and by some distance.

Built at a cost of about ¥60bn on reclaimed land on the outskirts of Osaka, the plant has stood for more than two decades as a masterclass in physical and political disguise. To a bemused passer-by, it is a beguiling fantasyscape of crooked lines and befuddling angles, representing one of the finest architectural works of the late Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser.

But, behind its boldly coloured walls, bucolic patterns and towers, are hidden vast Hitachi-built mechanisms: machinery that includes enormous claws for grabbing the startling quantity of mattresses and tatami floor matting that reach its grinders every day. Maishima processes almost a quarter of the household rubbish produced by Japan’s second city, and seals an unspoken pact between the Japanese public and its government.

After being cajoled over decades to meticulously sort their rubbish into categories before throwing it out, and after achieving one of the world’s highest rates of plastic (PET) bottle recycling, many Japanese would be forgiven for thinking most of its waste was similarly recycled. But Maishima — and more than 1,000 (considerably less beautiful) high tech incinerators around the country, including 20-plus in Tokyo — highlight a rather different approach. It is one that Japan has refined over decades and is eager to export elsewhere in Asia: burning rubbish to generate electricity.

Japan, even now, maintains an addiction to single-use plastic: bananas sold individually in plastic bags are often held up as an egregious example. But the country has little physical space for landfill (there is only one site in the whole of Tokyo) and it is not a major recycler among OECD countries: overall, only 20 per cent of household waste is reused. So it incinerates about 78 per cent, according to the OECD. And, over the past three decades, it has moved to reduce its fleet of small incinerators, which produced too many dioxin pollutants, in favour of large, expensive and extremely high-temperature plants such as Maishima.

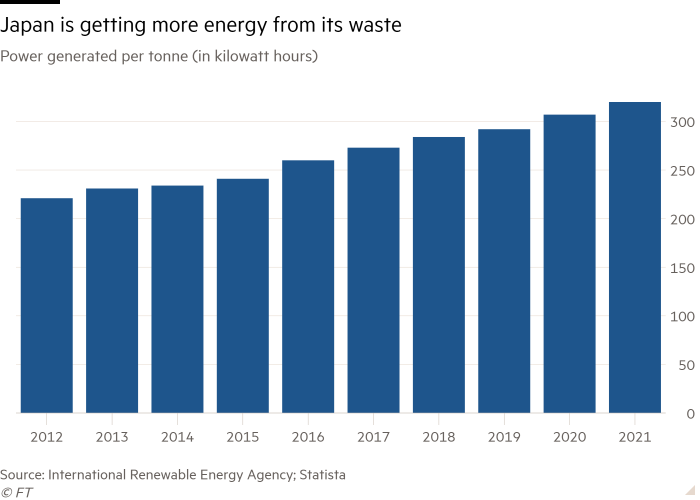

As the scale of these has expanded, and the technology has improved, a greater proportion of the electricity generated from incinerating rubbish can be fed back to the grid. Maishima — a 32MW plant — uses only roughly 40 per cent of what it produces to run itself. At the same time, other more modern plants, among the almost 400 waste-to-electricity incinerators elsewhere in Japan, are able to create even larger surpluses.

Critics of Japanese waste management policy argue that the incinerators are almost too successful. Even when they are less elegant than Maishima, they still provide an elegant solution to Japan’s generation of rubbish.

The plants’ efficiency, and the willingness of local government to meet the significant costs of construction and operation, allow the public to believe that its waste strategy is fundamentally “green”. However, in reality, it is generating greenhouse gases and providing the country, which imports the great majority of its energy, with a convenient alternative to aggressive recycling policies.

Kazuei Ishii, a professor of environmental engineering at Hokkaido University says that, whatever alternative policy suggestions might be offered, Japan’s commitment to incineration is effectively permanent — especially as the population becomes ever more concentrated in cities such as Tokyo and Osaka.

Japan had decided even before the second world war that incineration of rubbish was the optimum solution to the risks of pathogens and infectious diseases, Ishii says, and the lack of space for landfill remains a major constraint.

“Unlike in Europe and the US, Japanese municipalities — large and small — were able to build incinerators with central government subsidies,” Ishii explains, adding that both the continuing subsidies and the shortage of landfill options meant no serious challenge to the status quo was likely.

Another issue is that this long process of success and refinement has given Japan an exportable expertise.

South-east Asian countries, each struggling to manage their own challenges of excessive plastic waste, a surging consumer class, rapid urbanisation and limited landfill, are becoming increasingly eager markets for waste-to-power plants.

As a result, the Japanese government — including the Osaka municipal government which built Maishima — has made it an explicit mission to help create public-private partnerships in countries such as Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines, where the technology can still find a warm welcome.