In 1989, as the end of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership drew near, her government became the first in the world to privatise its entire regional water system.

Utilities in England and Wales were handed over to private enterprise, free of debt, in a bold move that proponents said would bring financial discipline and better management to the sector.

That theory faced renewed scrutiny this week after Thames Water was plunged into crisis by the exit of its chief executive and the revelation of contingency planning in Whitehall for a temporary nationalisation of the business.

The UK’s biggest and most highly leveraged water utility has been trying unsuccessfully to raise at least £1bn of new equity funding from its shareholders.

The crisis is set to reverberate far beyond the company itself. It could also be a moment of reckoning for how the UK organises and regulates its water utilities, potentially forcing a rethink around how the country can ensure investment in the sector’s creaking infrastructure.

Water regulator Ofwat has also warned about the financial situation of four other operators, underlining that the problems are not unique to Thames Water.

Thames Water’s travails marked the “beginning of the end of the privatisation model”, said Dieter Helm, professor of economic policy at Oxford university.

“This has been a massive regulatory failure and it could all have worked better if the regulators had done their jobs properly. Now it is probably too late to do more than buy a bit more time.”

This week’s turbulence at Thames Water, which has 15mn water and sewage customers, centred around two issues. The first was the sudden exit on Tuesday of its CEO, Sarah Bentley, who joined in 2020.

Bentley had been clear-eyed about the company’s problems, acknowledging openly that she had a “very long to-do list”.

On top of its financial problems, Thames Water was also being held back by operational issues, said people familiar with the company. “All the performance metrics stink,” said one adviser.

Bentley had launched an eight-year turnround plan for the business but left only a quarter of the way through.

The second trigger for the intense scrutiny was the revelation that government officials and Ofwat were working on a plan to deal with the potential failure of Thames Water. The price of its bonds plummeted as investors priced in the risk of a collapse. Shares in other water companies also fell.

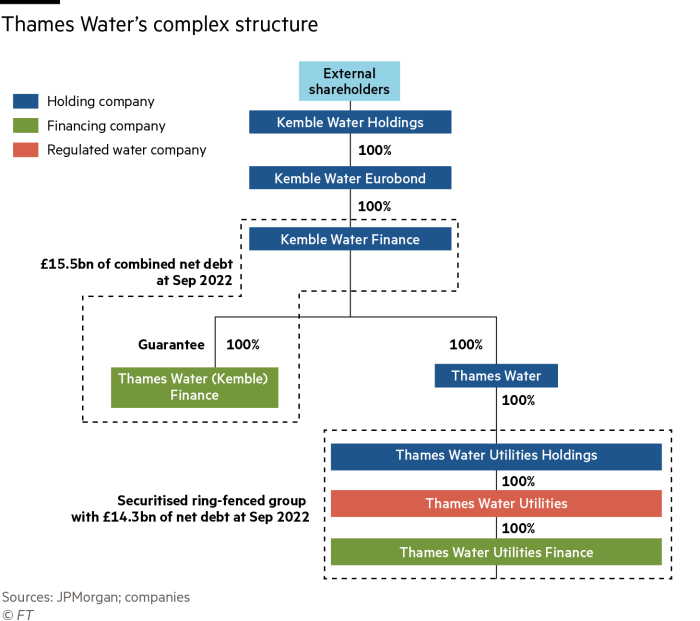

Thames Water is laden with £14bn of debt, which rising interest rates have made more costly to service.

Shareholders pumped £500mn of fresh equity into the business in March. The company had also publicly trailed an additional £1bn of investment, which is yet to materialise.

The question for shareholders, which include the Universities Superannuation Scheme and the manager of BT’s pension scheme, is whether they can stomach the risks involved in pouring more money into such a troubled business when some have not received dividends for years. Ofwat is also updating licence conditions so it can block dividends from April 2025 if any water company looks financially vulnerable.

USS, which holds a near 20 per cent stake in Thames Water, signalled support for the company on Friday. But the scheme underscored the importance of “the appropriate regulatory environment”, hinting at tensions between the government, Ofwat and the company’s shareholders.

Investors will also need to weigh the risk of backlash if they do not give the company the money it needs.

“If there is an emergency rights issue, it is absolutely crucial for the reputations of both USS and BT that they take it up,” said John Ralfe, an independent pensions expert. “Not only will it give them some more breathing space but they do not want to look like the baddies who brought down Thames Water.”

The government has the power to place a failing water company into a special administration regime — in effect a temporary nationalisation, similar to the 2021 takeover of gas and electricity provider Bulb Energy.

While officials have been war gaming that scenario, people close to the matter said they did not expect Thames Water would need such a process imminently. The company had £4.4bn of liquidity at the end of March.

“The problem we are facing is that all the negative publicity this week could end up making it harder for the company to raise the money it needs,” said one government official. “It’s not clear to me how they draw a line under this and stop the erosion of confidence in the entire sector.”

Until this week, Thames Water’s difficulties had been seen in Whitehall as localised, confined to the environment department (Defra) and Ofwat.

But media reports about the company’s plight have triggered concerns within the Treasury and Downing Street about the implications of rising interest rates for the entire industry.

Downing Street has tried to damp talk of a crisis in the water industry. A Number 10 source said some of the “speculation” about the sector was “a little overboard”.

But some politicians see the potential failure of Thames Water — and questions over the financial health of the wider industry — as part of the unravelling of privatisations launched a generation ago. Four rail companies have been nationalised in the past couple of years.

Increased discussion of nationalisation prompted Liv Garfield, the boss of Severn Trent, to invite rivals to a secret meeting to avert the threat, suggesting they consider reinventing themselves as “social purpose companies”.

Rebecca Pow, the Conservative water minister, insisted in a debate in the House of Commons on Wednesday that the sell-off of the water industry had been a success: “Privatisation has enabled clean and plentiful water to come out of our taps,” she said. “It has unlocked £190bn of funding to invest in the industry”.

But opposition MPs lined up to criticise the way investors had loaded up water companies with more than £60bn of debt while underinvesting in infrastructure and paying lavish dividends to their shareholders — leaving the industry vulnerable to rising interest rates.

Thames Water’s former owner, Australian investment powerhouse Macquarie, took out nearly £3bn in dividends over 11 years before selling the business, whose biggest shareholders are now an assortment of pension funds, private equity and sovereign wealth vehicles.

Feargal Sharkey, the rock star turned clean water campaigner, believes the government should take more direct control over the companies, even if they are not nationalised. “Clearly we all agree not a penny of public money should go into any bailout for these companies,” he said. “They’ve made off with £72bn of our cash, they’ve ram-raided these companies for cash.”

£14bn

Thames Water’s debt. £500mn of fresh equity was invested by its shareholders in March

15mn

The number of customers who are served by Thames Water

78yrs

The average age of the water trunk mains in Thames Water’s network

The water industry has become an object of public scorn as awareness has grown of the extent of sewage discharge into rivers and beaches.

The government has told water companies they need to find £56bn to deliver a huge upgrade of the system over the next 25 years, which would require a big uplift in customer bills.

The conundrum facing the government, say investors and people in the industry, is to find a model that will deliver the investment needed to maintain and improve the country’s ageing infrastructure.

London’s largest water main pipes, some of which are so big scuba divers have to be called in to carry out repairs, are more than a century old.

The chief investment officer of one large pension fund said the regulation of water pricing needed to change to attract more private money to the sector.

“It is very simple what needs to happen. The price of water needs to go up,” the person said.

Allowing private companies to raise prices during a cost of living crisis would be unattractive for ministers but putting the companies into public hands — the prevailing model internationally — could add to pressures on government finances.

A former water industry executive said chronic under-investment long predated the privatisations of 1989 and that any form of nationalisation risked a repeat of decades of under-investment in the 20th century.

“If the government takes this back into its hands, it won’t get the money it needs,” he said.

But with pressure from protesters on sewage-filled beaches pressing for renationalisation and a YouGov poll last year finding that 58 per cent of Conservative voters believe water should be brought back under public control, the debate is set to run.