Receive free Thames Water PLC updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Thames Water PLC news every morning.

The turmoil at the top of Thames Water has left the UK government scrambling to prepare contingency plans in the event of the collapse of the heavily indebted utility.

Less than 12 months ago, Thames Water published its own assessment of the long-term viability of its business. The conclusion: the company was in good financial health.

And yet this week government ministers were discussing whether a temporary nationalisation of the company could be necessary, after the unexpected exit of chief executive Sarah Bentley, who resigned for “personal reasons”. Panic around the group’s prospects in the wake of her departure sent the value of bonds at Thames Water’s holding company plummeting into distressed territory.

How did a heavily regulated company that has long maintained a high debt burden suddenly come to look so shaky? And what is driving the strain on Thames Water’s balance sheet?

Shareholders are dragging their feet

The board of directors’ prior confidence in Thames Water’s finances was based on a number of assumptions, but foremost among them was their belief that the company’s existing shareholders would pump £1.5bn more equity into the business, to help boost its “financial resilience” and turn around flagging performance.

Rating agency Moody’s warned in a December report that the company’s credit rating was at risk of a downgrade if the additional investment failed to arrive.

As of this month, the company had received just £500mn from its backers which include the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, the UK’s Universities Superannuation Scheme pension fund, as well as the Chinese and Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth funds, and infrastructure fund Aquila GP. The further £1bn has not yet materialised.

The investors all declined to comment.

Putting more money in may be a case of throwing good money after bad, as potential returns are likely to be damped by growing regulatory scrutiny and a recent policy change that the water regulator announced in March. The change enables Ofwat to stop shareholders paying themselves dividends if these would put the company’s financial health at risk. Thames Water’s former owner, Australian investment powerhouse Macquarie, took out nearly £3bn in dividends during its 11-year ownership period.

Legacy of indebtedness

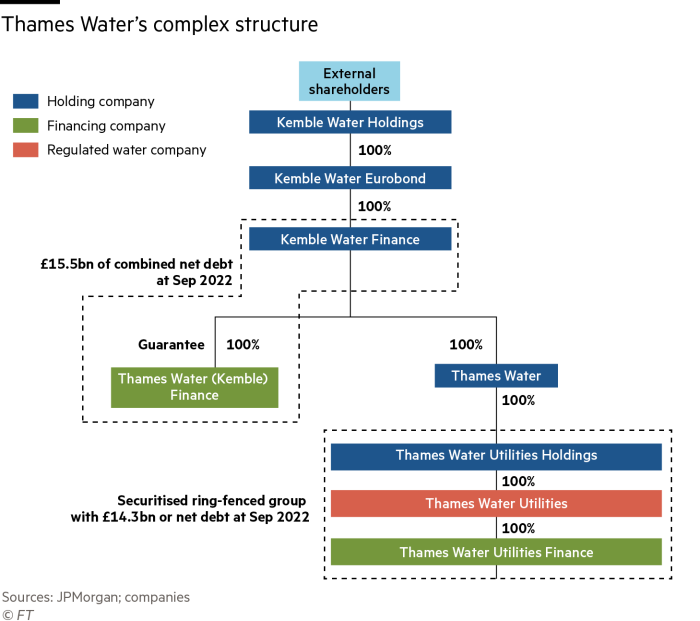

Thames Water and its holding companies have total gross borrowings of £15.9bn (£15.5bn net of any cash), a legacy of its 2006 leveraged buyout by Macquarie.

Of that amount, £14.5bn takes the form of a whole-business securitisation, a structure commonly used to borrow against highly regulated assets with predictable cash flows. The rest are bonds and loans in a series of holding companies under the Kemble umbrella.

Strict terms in the securitisation bonds can restrict cash from being sent to service the Kemble debt if the regulated utility comes under pressure. On Wednesday, the value of a £400mn Kemble bond maturing in 2026 plummeted on news the UK government could step in, falling around 30 pence to 56p in the pound, showing bondholders are braced for potentially steep losses.

Concerns around the sustainability of Kemble’s debt could threaten shareholders’ investment, as equity is always subordinate to debt.

Exposure to surging inflation

Surging inflation might at first glance appear beneficial for a regulated water company that is able to pass on costs to its consumers. But a mismatch between the measures of inflation Thames Water uses to hedge its debt and to price its customers’ bills has caused a growing strain on its balance sheet.

More than half the group’s debt is linked to inflation, meaning interest payments increase as inflation steps up, which the company has justified by noting that customer bills are also linked to it. However, the debt is linked to one measure, the retail prices index (RPI), which is at a historically wide premium to the other, the consumer prices index adjusted for housing costs (CPIH), which the majority of its bills are now priced against (see chart).

The 2022 annual accounts of parent company Kemble Water Holdings show that the weighted average interest on the group’s £7.7bn of “index-linked debt” soared to 8.1 per cent from just 2.5 per cent the previous year.

The accounts also warned of more potential pain ahead. An “inflation risks sensitivity analysis” — which conceded that the RPI-linked debt only acted as a “partial economic hedge” — showed that a 1 per cent increase in the rate of inflation after 31 March 2022 would dent the group’s profit and equity by £911mn.

While Thames Water put in place a new £1bn hedge in November 2022 to “help manage inflation risk”, it could be a case of too little too late.

Operational issues abound

The company is facing a multitude of challenges aside from its large debt pile and unwillingness from investors to put in more money.

The impact of inflation and increasing regulatory scrutiny have both put pressure on the company’s earnings which fell by 6 per cent from March to the end of September last year. A cost of living crisis has made it harder for households to pay their bills, which could pose risks to the company’s financial performance, it said in its annual report published last year.

Thames Water has also been involved in several high-profile sewage pollution incidents which have led to the business — along with several other water companies — being placed under criminal investigation by the Environment Agency, as well as a separate investigation by Ofwat. The EA investigation, which is examining the water company’s compliance with storm sewage discharges, remains ongoing.

The company has also struggled to make progress on leaks, which have reached their highest level in five years, according to a freedom of information request released earlier this week. The company will not meet its target to reduce them this year.