The flood of cash pouring into US money market funds is unlikely to stop soon, analysts and investors say, and has the potential to exacerbate strains in the banking system.

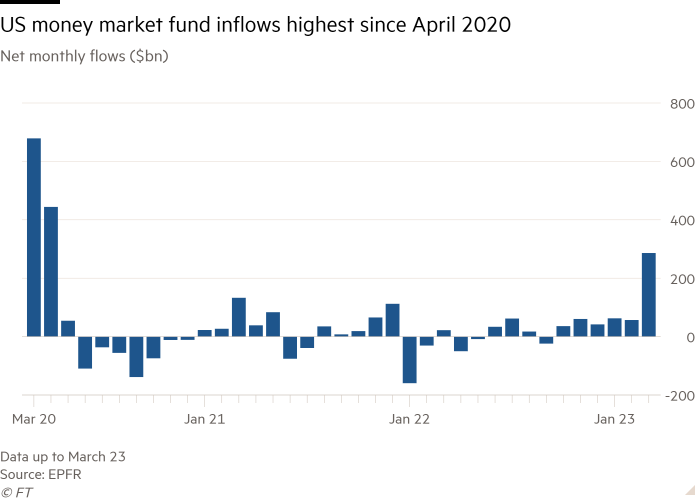

The returns offered by money market funds, vehicles that invest largely in safe assets such as short-term government debt, have soared far above the interest rates banks pay to depositors, as the Federal Reserve rapidly raised borrowing costs over the past year. Despite the yawning gap, it took the banking crisis sparked by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank to spark the recent stampede: money market funds have drawn in more than $340bn since the beginning of March.

“People that were making half a per cent in bank accounts were ignoring the 4 per cent they could make in money market funds,” said Doug Spratley, head of US money market trading at T Rowe Price. “And now they just got a big swift kick in the pants.”

The recent flows into money market funds have drawn the attention of Treasury secretary Janet Yellen, who on Thursday warned over the “structural vulnerabilities” of the sector.

“If there is any place where the vulnerabilities of the system to runs and fire sales have been clear-cut, it is money market funds,” she said in a speech at a conference hosted by the National Associations of Business Economics. “The financial stability risks posed by money market and open-end funds have not been sufficiently addressed.”

Some experts have warned that shift into money market funds also further threatens the stability of the banking sector, particularly the smaller regional lenders that can least afford to increase the interest rates they offer to account holders.

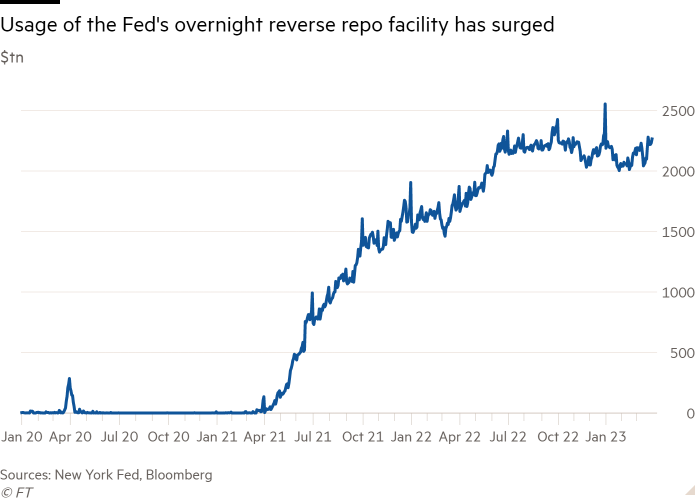

Crucially, much of the cash in money market funds ends up outside of the banking system altogether because the funds are heavy users of a Fed facility that offers generous interest rates for parking cash overnight at the central bank.

For Andrew Levin, who worked at the Fed for two decades, the unrelenting flow of cash into money market funds and in turn the central bank’s overnight facility is “an accident waiting to happen”.

Usage of the so-called reverse repo facility has climbed in recent weeks, with daily levels running at about $2.3tn.

Levin, who now teaches at Dartmouth College, warned of added strain on smaller lenders if more depositors park their funds into money market entities, which eventually get stashed at the Fed. “Ironically for the Fed, which wants to try to help the banking system and help keep [it] safe, its own standing facility ends up being the weak link in all of this.”

Because money market funds are not deposit-taking institutions, their assets, were they not in the Fed facility, would still be in the banking system. But their use of the facility leaves banks collectively with fewer deposits, and potentially disincentivised from lending.

Concerns about a downturn in the economy might mean that some banks “may not be as eager to lend” anyway, suggested Tatjana Greil-Castro, co-head of public markets at Muzinich, and “therefore they don’t need as many deposits”.

Even so, some analysts worry about the destabilising potential of further flows. While the shift out of banks and into money market funds is one that typically happens during every cycle of Fed interest rate rises, experts are suggesting the move could persist even once the central bank ends its monetary tightening and begins to lower borrowing costs.

Banks are in the middle of a “two-stage shift”, said Joseph Abate, a strategist at Barclays in a note published on Wednesday. The first wave of outflows happened as savers worried about the stability of their banks, a phenomenon which drove assets in government money market funds to a record high of $4.3tn this month, according to ICI data.

In the first two weeks of March, overall bank deposits in the US dropped by $161bn, driven by outflows from smaller banks, according to Fed data.

The second shift, however, is only just beginning, as “sleepy depositors” — until now little troubled by the widening gulf between yields on bank deposits and those available elsewhere — awaken to that stark disparity.

Money fund balances have climbed roughly 20 per cent over the past four rate-rising cycles, according to Abate, a move that would be equal to roughly $1tn this time around. So far, they have risen by about $600bn during the current cycle, suggesting there is more to come.

The recent ructions across the US banking sector also mean that even if banks raise the interest rates they pay on deposits to better compete with funds, savers may be deterred by the perceived risk in the system.

Because money market funds invest in short-dated government debt that is highly sensitive to moves in Fed borrowing costs, “your yield is going to come down with interest rates”, said Joseph D’Angelo, head of money markets at PGIM Fixed Income. “But that doesn’t necessarily mean fund outflows, because you’re not necessarily going to see deposit rates come up.”

“In all likelihood, I don’t see a lot of movement back.”