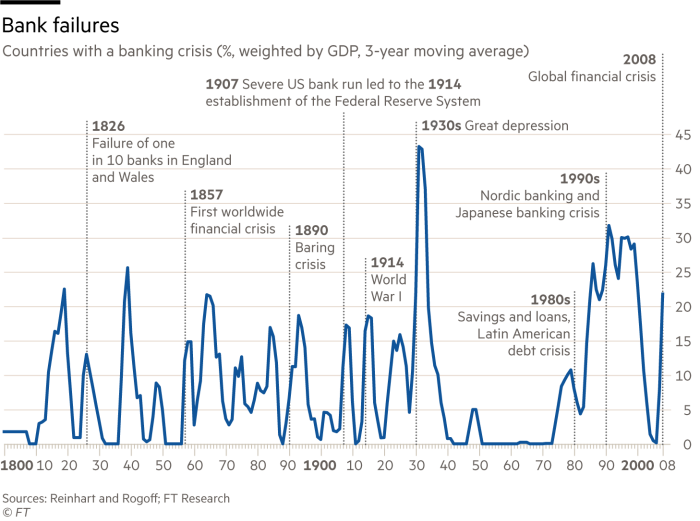

Bank runs in the digital age are extraordinarily swift. The demise of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse have demonstrated that. But at heart, bank runs are old-fashioned affairs. With the exception of a few decades of calm after the second world war, such crises have occurred regularly. Most follow a pattern that is centuries old.

Speculative booms, large capital inflows or financial liberalisation are common precursors. The proximate cause is often falling asset prices. Depositors’ subsequent flight to safety causes contagion. The consequence is a credit crunch, depressing production and employment. Nearly half of all US business cycle downturns between 1825 and 1914 involved big banking crises.

Remedies have been long debated. A banker first floated the idea that the Bank of England should act as a lender of last resort in 1797. At first, the Old Lady — then a private bank with some public responsibilities — did not play ball. Its initial response — later reversed — to the 1825 banking panic was to protect its reserves, ration lending and raise its discount rate. More than one in 10 banks in England and Wales had failed by 1826.

That crash prompted legislation allowing banks — then small, poorly capitalised partnerships — to incorporate. But limited liability only became mainstream after the failure of the City of Glasgow Bank in 1878. The gulf between its assets and liabilities punctured the notion that unlimited liability guaranteed the bank. That drama has resonance today, as post-2008 rules intended to make shareholders bear the brunt of any bailout are put to the test.

Another early response to bank runs was deposit insurance. This was first introduced in 1829 by the US state of New York. Just over a century later, a federal insurance system was introduced in response to the collapse of more than 9,000 banks in the Great Depression. It has recently — and controversially — been extended to cover all the depositors of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature.

The rescue effort sets expectations for future bailouts dangerously high, say critics. That adds to long-running concerns about moral hazard. While intervening in bank runs limits the damage, it dilutes the incentive to guard against financial risks. No wonder many financial regulators pay close attention to history. Their tools and understanding are more sophisticated than in the past. But the underlying dilemma is not much changed.