The labor market continued its energetic expansion in February, extending a hotter-than-expected streak that has created abundant job opportunities while frustrating the Federal Reserve in its drive to contain stubborn inflation.

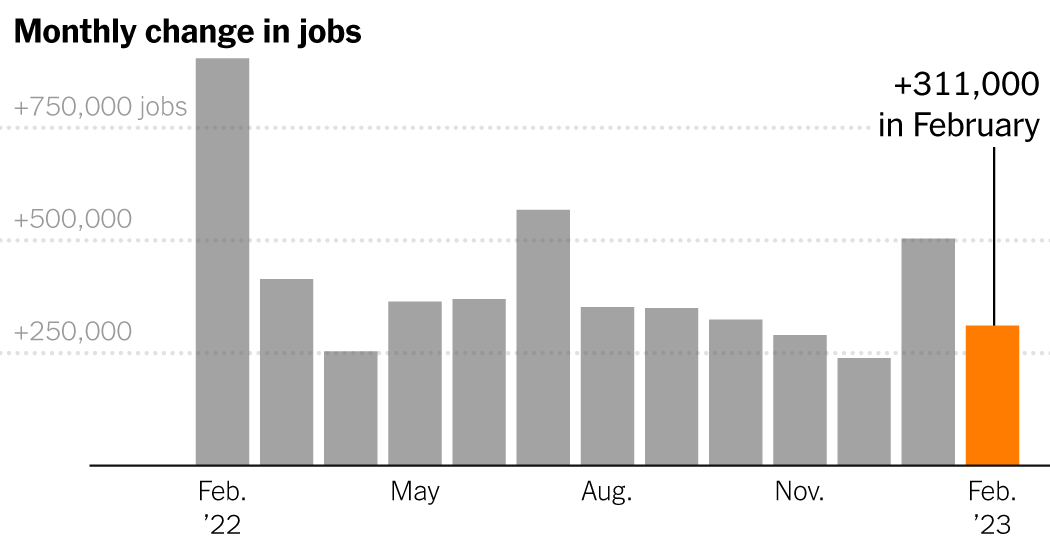

Employers added 311,000 jobs, the Labor Department reported Friday, down only slightly from the average of 344,000 over the previous three months. The unemployment rate ticked up to 3.6 percent, from 3.4 percent in January, which was the lowest level since 1969.

Hiring has been a persistent source of dynamism in the economy since the pandemic lockdowns eased, even in the face of interest rate increases that have raised fears of a recession.

In remarks at the White House, President Biden hailed the jobs report as a sign that his administration’s policies had helped sustain the American economy. “Today’s jobs numbers are clear: Our economy is moving in the right direction,” he declared.

But there were signs in the February report that the job market’s extreme tightness might be easing.

Overall, an influx of more than 400,000 job seekers lifted the labor force participation rate, which has been slow to recover as older people retired early. The rate for those in their prime working years — ages 25 to 54 — jumped to 83.1 percent, finally exceeding its prepandemic level.

Wages grew 0.2 percent from January to February, a continued deceleration and the smallest increase since February 2022. And the average workweek shrank slightly, another indication of reduced demand for workers that is likely to provide some comfort to Federal Reserve policymakers, who have closely watched earnings as a driver of inflation.

Inflation F.A.Q.

What is inflation? Inflation is a loss of purchasing power over time, meaning your dollar will not go as far tomorrow as it did today. It is typically expressed as the annual change in prices for everyday goods and services such as food, furniture, apparel, transportation and toys.

The central question around the Fed’s strategy is whether higher interest rates can take the air out of price increases without throwing millions of people out of work. So far, inflation has been easing slowly, but continued job gains have brightened the consumer mood. That has powered a turnaround in retail spending and moved economists’ projections of an impending recession further into the future — if it happens at all.

Part of the resilience in hiring reflects Americans’ continued desire to return to their pre-2020 habits of going on vacations and eating out at restaurants. “Some of these sectors, especially services, are still recovering from the pandemic,” said Eugenio Alemán, chief economist at the financial services firm Raymond James. “I think that puts the thought of a recession kind of in doubt.”

Leisure and hospitality added 105,000 jobs, putting the industry 2.4 percent below its level three years ago. Construction, which has grown steadily even as the housing market entered a deep freeze, also continued to add jobs, as did health care, retail, and professional and business services.

Other sectors, however, have clearly lost momentum. The information industry, which includes many large technology companies, subtracted 25,000 jobs as layoffs hit in Silicon Valley. Goods-related industries were flat to negative, as retailers have burned through their bloated inventories, reducing the need for new orders and for truck drivers to move things around. Manufacturers shed jobs for the first time since April 2021.

At any other time, raising the key bank lending rate from zero to an average of 4.5 percent in less than a year might have prompted widespread layoffs, as capital becomes more expensive and business expansions suddenly no longer pencil out. But the reopening from pandemic lockdowns, combined with workers’ reluctance or inability to seek jobs, made employers extremely reluctant to cut payroll even when business dipped.

That has allowed overall employment to expand even as hiring has slowed considerably.

“Something we all missed in the last cycle is we never know if companies have excess workers,” said Susan Sterne, principal at the consumer-focused consulting firm Economic Analysis Associates. “If you tell everyone there’s a shortage of labor, you probably keep workers longer than you would otherwise. So that becomes a very significant question mark.”

That’s an everyday reality for Vimal Patel, who owns a portfolio of hotels in southern Louisiana, where his main clientele is oil and gas crews. He has struggled to operate at full capacity because of high turnover, even after raising wages to a range of $13 to $15 an hour for housekeepers, and higher for the front desk staff. To maintain a full roster, he keeps recruiting even when positions aren’t open and has engaged a staffing company to fill in gaps.

“That’s how we’re mitigating right now, because we’ve got to have staffing,” Mr. Patel said. “That practice has eroded most of the profits, and we are barely breaking even.”

One driver of staffing instability: Rising prices spur workers to seek better-paying jobs, if they’re not able to get big enough salary bumps to cover their suddenly higher costs.

Monica Cole had worked as a legal advocate for foster children north of Seattle since graduating from college in 2019. When her landlord said her rent would be going up by about 8 percent — a new local law requires six months’ notice of increases — she knew she would need to defer her plans to go to law school and look for another job, because her contract position did not allow for raises.

Fortunately for Ms. Cole, the state health agency needed investigators in adult protective services, and offered her a 30 percent raise. She started in February and plans to stay in state government, which offers solid benefits, annual raises and routes for advancement.

“It’s not the path I’d hoped I’d be on, but realistically, being able to pay my bills is important,” Ms. Cole said. “Working for the state will let me do that in a way that unfortunately that other position, which I really loved, wasn’t going to enable me to do.”

Understand Inflation and How It Affects You

The latest batch of data adds to a cacophonous landscape of economic indicators, some of which suggest that businesses and consumers are ramping back up after absorbing the Federal Reserve’s largest interest rate increases in 2022. Others, like the share of workers quitting their jobs, continue to sink back to earth after extraordinary surges over the past three years.

Perhaps the most important data point for the Fed will come on Tuesday with the Consumer Price Index reading for February. The measure increased on a month-over-month basis in January after several months of cooling, raising fears of a fresh acceleration in price growth.

Earlier this week, the Fed had been expected to stick to a slower course on interest rate increases, moving in increments of one-quarter of a percentage point. But Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, warned in two hearings on Capitol Hill that if new data showed that the economy was not slowing enough to keep inflation in check, policymakers might opt for a bigger increase at their meeting on March 21-22.

That could prompt a sharper downshift in labor demand, to the point where employers are forced not just to pull down job postings, but also to hand out pink slips.

“The big upshot is that it lowers the chances of a soft landing a little bit,” said Brad Hershbein, a senior economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, referring to February’s continued growth in payrolls. “The broader pattern is still consistent with the labor market gradually cooling, but more gradually than the Fed would like.”

Katie Rogers contributed reporting.