In a cockpit somewhere over the clouds, Suwapich “Windy” Wongwiriyawanich lost sight of the curvature of the earth. There was to one side of her, the receding night sky and to the other, the glow of day breaking. “This is the place I should be,” the flight attendant mused. “Here in front of the plane — not in the back.”

Those five minutes, floating between Thailand and India, set a new course for Suwapich. She applied to AirAsia’s first class of Thai cadets, clocked 2,000 flying hours, and became one of its first women pilots. Two decades on, Capt Windy still catches passengers by surprise when the timbre of her voice spills out of a plane’s speakers.

Windy’s journey from cabin to cockpit is part of a wider story as more women across Asia take the controls in professions long dominated by men.

Women claiming new spaces, and clamouring for equality in them, is creating ripple effects for the larger gender ecosystem and for generations to come.

For the first time in history, women in Asia now hold more combined wealth than in any region except North America, and the total is growing more rapidly than anywhere else in the world.

Charting new vocational terrain, women in Asia (excluding Japan) are adding $2tn to their wealth each year and will hold $27tn in 2026, according to analysis done by Boston Consulting Group for Nikkei Asia this year. That is $6tn more than forecast for women in western Europe.

The surge is driven, in part, by women venturing into careers previously home only to men.

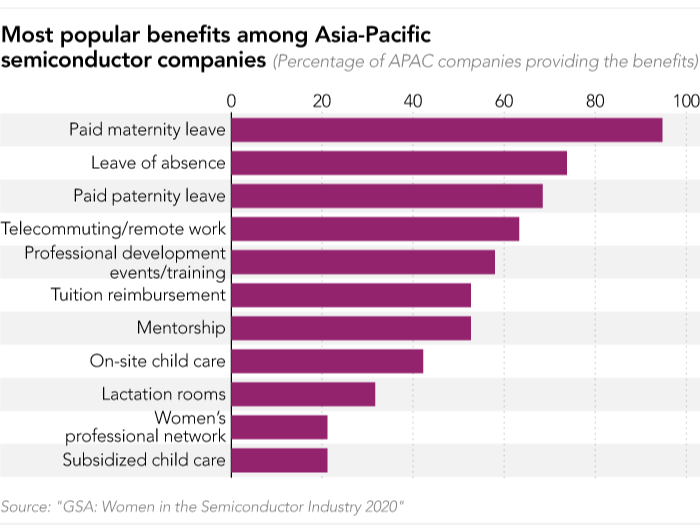

Also at play are factors such as parental leave and social structures, including reproductive rights and child care in homes with three generations or relatively cheaper nannies.

“Female workers, whether they work online or offline, who have some family support, have greater flexibility to work longer hours and expand their business,” said Hue-Tam Jamme, an assistant professor at Arizona State University. She is also a fellow at JustJobs Network, a labour think-tank whose research in Thailand and Cambodia shows women do twice as much unpaid care work as men.

Rising levels of education, urbanisation and travel have also reshaped gender mores.

But despite the glossy statistics and rising employment, women remain the second sex financially — they will need 151 years to close the economic gap with men if nothing changes, the World Economic Forum said in a report that measured pay, unemployment, access to finance and land, among other data.

In many places, women are also fighting conservative families to carve out paths for themselves that are still considered unorthodox. Ishmita Nagi, a former fashion designer who swapped one runway for another when she became a pilot at Indian carrier IndiGo, said she has crossed paths with many such women. “I salute those girls . . . because I don’t think that without the immense support that I have had from my family I could have come so far,” she told Nikkei Asia in an interview.

Poverty and location also lead to significant variations within a country.

On a crisp, sunny winter morning, 13-year-old Jahanara Alam was on her way to volleyball practice in Khulna, about 200 kilometres from Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka. Dressed in sports attire, she was spotted by a cricket coach and asked if she might be interested in the sport. It was 2006, and Bangladesh was about to assemble its first national women’s cricket team. Stunned into acceptance, Alam went into training.

Alam’s team went on to take silver at the 2010 Asian Games, and in 2018 pulled off a surprise win against defending champions India at the Women’s T20 Asia Cup. She was also the first Bangladeshi bowler to take a five-wicket haul in women’s T20 international cricket.

At the other end of the subcontinent, Urooj Mumtaz grew up playing cricket behind a carpet factory in Karachi, Pakistan. As a teen, she was captaining a boys’ team at the local club. “There still isn’t a girls’ team at the club,” Mumtaz told Nikkei Asia in an interview.

In 2006, she went on to captain Pakistan’s national cricket team, and later became the country’s first woman to commentate on an international men’s match.

Both Alam and Mumtaz have managed to score a few wins on equality in their countries. Basics such as airfare, accommodation and gear have been secured, but several innings remain to achieve pay parity.

“If the [men] are getting 100 per cent then we are getting maybe 30 to 40 per cent,” Alam said in an interview, noting the gap was narrower now than when they were making 5 to 10 per cent a decade ago. Mumtaz said there was a fivefold gender pay differential in the highest category of cricket in Pakistan.

Appreciation From Urooj Mumtaz is Beautiful when she Says The King 👑 is back in style 👌👌♥️♥️ I just Say wow 🤩 Love u ho gya 🥳🥳🥰🥰 #PakVsAustraila #BabarAzam𓃵 pic.twitter.com/VuxuNBBwfO

— معظم چوہدری (@moazam87) March 15, 2022

“When you get better facilities, when you pay them better . . . when you give them better travel, better hotels to stay at, everything translates into better results,” she said.

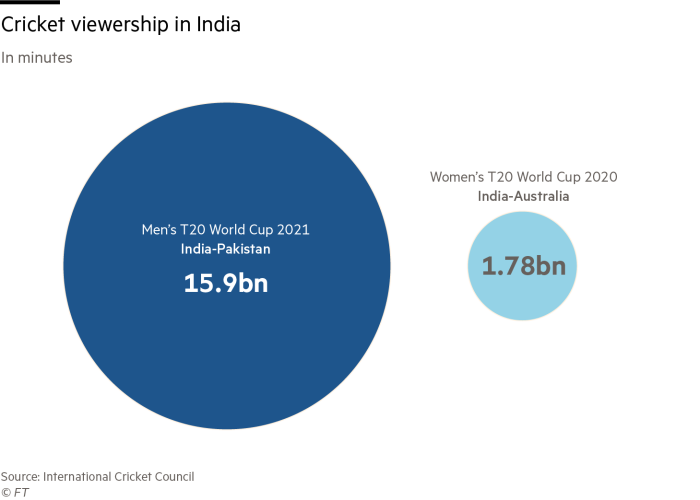

Several players and branding agencies have called on cricket boards to sharpen the spotlight on female cricketers via marketing campaigns. More fans would mean bigger television audiences and the promise of lucrative endorsement deals, which can run into hundreds of thousands of dollars for individual cricketers.

India in October announced equal cricket match fees for women and men, following a similar edict by New Zealand in July. The move was cheered by many across the game, including legendary former Indian captain Sachin Tendulkar.

Yet for all the progress, the current system keeps producing similar results year after year: men outnumbering women in the most powerful and well-paid posts. One systemic reason is hiring. Human recruiters rely partly on professional networks, often dominated by men, while algorithmic recruiters rely on historical data that refer to prior people in those roles — also often men.

Gendered structures and social conditioning can also disadvantage men, says Yen Do, a Vietnamese investor focused on gender equality. “Men also bear tremendous social biases, [that they] should be the sole or main breadwinners, should have enough money and assets to find a wife,” she said.

When top chip companies, from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) to Qualcomm, want to know what ails their integrated circuits, they call Dr Hsieh Yong-Fen. Taiwan’s first female PhD in materials science and engineering sees the business she founded, MA-tek, as a technical doctor that diagnoses problems in research, design and production.

“There are no stereotypes and gender barriers in my company,” Hsieh said in an interview at her office in the chip hub town of Hsinchu, where she leads meetings by drawing colourful graphics on floor-to-ceiling whiteboards that blanket two walls.

Taiwan dominates the world’s supply of computer chips, which run everything from phones to laptops and cars. Nearly 30 per cent of MA-tek engineers are women in an industry striving for parity.

At TSMC, which accounts for more than half of the global market for contract chip fabrication, women make up 13 per cent of managers and 21 per cent of technical hires — still less than the company’s 2030 targets of 20 per cent and 30 per cent, respectively.

Over in Vietnam, where Intel has its largest global assembly site, 33 per cent of its technical staff are female. This is short of the 40 per cent it aims to have in five years.

Ho Thi Thu Uyen has been with Intel since it entered Vietnam in 2006, becoming the first Vietnamese senior manager at the US company, one of Ho Chi Minh City’s biggest exporters.

“When [girls] are in high school, we have student sessions, we invite them to tour the factory, we have female engineers talk to the students,” Uyen, now a public affairs director, told Nikkei Asia, adding there are internships and “a lot of support so that they feel more confident in choosing engineering and technology”.

The semiconductor firms are starting to break past an event horizon. Research shows “when women make up at least 30 per cent of a particular [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] field, other women are drawn to that field . . . the belief being that the behaviours, interactions, and culture of the field have been influenced by women, and issues such as power dynamics and feelings of isolation are less problematic,” Roberta Rincon, associate director of research at the Society of Women Engineers, told Nikkei Asia.

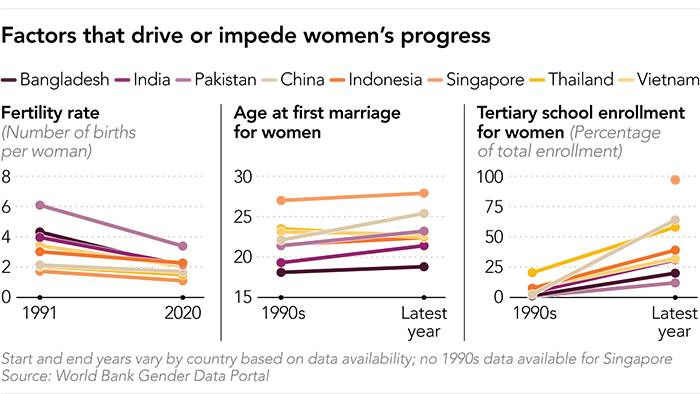

In addition to representation, studies show a correlation between reproductive rights and women’s wealth.

The impact of children depends, first, on a woman’s right to choose and, second, on the care available. Though abortion rights vary widely across Asia, they are relatively strong in some countries. The region accounts for nearly half of the world’s 73mn terminations a year, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

That stems in part from son preference. Yet it also reduces the odds of unintended pregnancies that force mothers to quit the workforce.

Data from the World Bank also show that women in the region, on average, are having fewer children.

Yen Do, an investment manager at Beacon Fund, which backs female entrepreneurs, believes greater education and urbanisation are changing views about gender roles.

The Asian Development Bank puts urbanisation in the Asia-Pacific at 54 per cent, rising to 64 per cent by 2050.

For one segment of the region’s working mothers, child care comes from an army of affordable domestic helpers; for another, it’s live-in grandparents. Three-generation households are more common in Asia and Africa than the rest of the world, according to the United Nations.

Capt Jul Laiza C Beran, the first female fighter pilot in the Philippine Air Force, will have help from a nanny and in-laws when she has a child next year. After maternity leave she’ll need to retrain, fly sorties with an instructor, and stay fit for a job with intense physical demands like withstanding gravitational force at high altitudes.

Beran enlisted in the military after a childhood of midnight evacuations and pitched battles between the army and separatists in Cotabato province in the country’s south. “I wanted to take the road less travelled by women and prove that a woman could be a combat-ready pilot and man stealth aircraft,” she said.

Nivedita Bhasin was awed by aircraft she saw as a girl. In New Delhi, she’d stare out her classroom window, dreaming of flying the planes that soared past. One day, an algebra teacher hurled a piece of chalk at Bhasin and yelled, “Well, you’ll get a big zero if you keep looking out the window.”

Thirteen years later, in 1989, Capt Bhasin became the youngest woman in the world to command a commercial jet aircraft; she was 26. “It turned out that I had to look out the window. That’s the job, that’s how I earned my living,” she said.

Bhasin reported back to work when each of her two children was six weeks old. “This is really heart-wrenching when I think of it now,” she said in an interview. Her airline had no rules about pregnancy; she was India’s first airline pilot to have given birth.

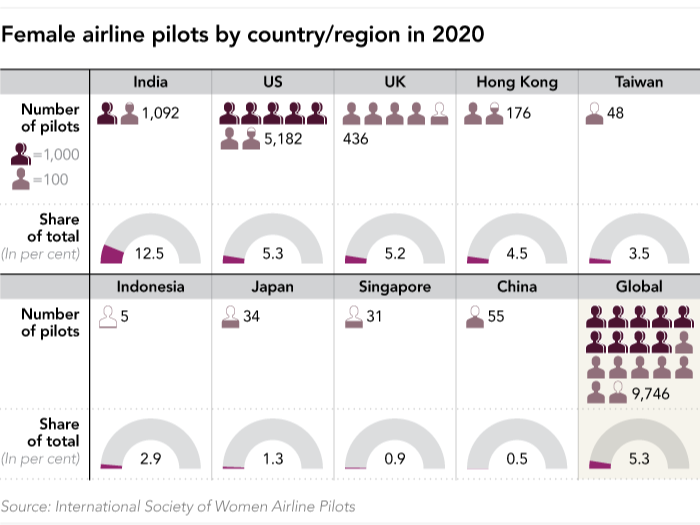

The country has the world’s highest proportion of female pilots, 12.5 per cent, the International Society of Women Airline Pilots estimates.

Yet this is also a country that ranks 135 of 146 on the World Economic Forum’s ranking of nations based on gender parity. With 662mn women, India lags in overall labour force participation, healthcare, the female-to-male literacy ratio, income equality and representation in political, technical and leadership roles, the WEF said.

But when it comes to taking to the skies, trailblazers like Bhasin say women pilots in India have benefited from active outreach, including state subsidies for expensive flight schools. Private companies, such as Honda Motorcycle and Scooter India, provide full scholarships for 18-month training sessions and placement at commercial airlines.

Women who show up on turf that had long been considered the preserve of men don’t always get a warm welcome. “Well, it’s still called a cockpit.”

Capt Beran, who became a pilot 30 years later, has had a smoother ride. At first, air force protocol catered to men, from bathrooms to safety gear. But it adapted, and Beran now feels camaraderie with her male colleagues — important for the high-stakes, dangerous missions they execute together.

“It’s a very risky aircraft, fast and powerful,” she said. “All you can think about is performing a scramble or hitting the target or flying in formation. There’s pressure on your mind and body.”

Commuters may be used to hopping in a taxi to be greeted by a male driver, but more women are taking the wheel.

Companies such as Thailand’s GrabCar for Ladies and India’s Hey Deedee delivery women fill a gap in the market.

“From the safety point of view also, it is good to have female clients who, too, feel comfortable with a woman driver,” said Pooja, a taxi driver in New Delhi who goes by one name. She had stints driving for Uber, Ola and a private client, but moved to part-time work with the birth of a daughter in 2020.

The gig economy has attracted women who say apps like ride-hailing or bTaskee, Vietnam’s odd jobs platform, allow freedom to set schedules around child care or other activities. This was the top motivation cited by Indonesians and Indians when polled by Uber for a 2018 report.

In 2018, Grab reported an annual jump of more than 230 per cent in south-east Asian women drivers. But the pandemic has accentuated a long-running debate about whether flexibility, including remote and gig work, helps or harms women. “The platform economy tends to reproduce rather than overturn traditional gender roles, while adding extra working hours to women’s busy schedules,” said JustJobs Network’s Jamme.

Her research found that when women do gig jobs, they have less leisure time and lack access to healthcare, pensions, and training.

The Friedrich Ebert Foundation’s 2020 report on women in Asian economies drew similar conclusions, suggesting: “Rethink the social-protection infrastructure to better include those who work from remote locations or in flexible work environments.”

In Thailand, marketing professional and part-time Grab cab driver Suthamat drives for another kind of freedom: financial. “I’m a working girl. I don’t want to just stay home and do nothing,” she said, weaving her sedan through Bangkok’s gridlock. Her husband and sons encourage her to retire but she prefers to make money, enabled by independent contractors’ low barriers to entry.

As women move into cities, they “get exposed to a freer life”, said Beacon’s Yen. That includes more freedom to work and absorb the urban marketplace of ideas, such as who can be an executive or an engineer or an athlete.

As Suthamat and others accumulate savings, they are moving it into more financial products, prompting banks such as UBS and HSBC to introduce services for female clients.

Women who earn more than $75,000 a year and hold assets worth between $100,000 and $1mn, the mass affluent, are a high-growth target market.

“Asia’s mass affluent women are becoming more financially savvy, confident and active in their investments” and “managing and growing their wealth more than ever before,” said Jenny Wang, head of premier wealth solutions at HSBC. The number of women in this category in Asia has risen 14 per cent since the pandemic started, she said.

The ranks of women on the other side of the desk are also growing at banks like BDO in the Philippines and JPMorgan Asia. Women make up 30 per cent of the region’s wealth managers versus 10 per cent in Europe, says recruiting firm Korn Ferry.

Wing Commander Namrita Chandi was in the second batch of helicopter pilots allowed into the Indian Air Force and the first woman in her family to earn a pay cheque.

While she felt no discrimination on the job, organisational policy lagged the times. Women were allowed only short-service commissions, so Wing Commander Chandi was forced to retire after serving for 15 years.

She moved to the courts, and after an eight-year fight, the Supreme Court of India ruled that the defence forces had to allow women to become permanently commissioned officers. Short-service officers miss out on benefits that lead to wealth, most notably a career path to the top and pensions.

“This is for the next generation of women. I hope they can make a difference to humanity and a greater difference to the world.”

The Indian Air Force allowed women fighter pilots as an “experimental scheme” in 2016, and announced this year it would make the move permanent.

Institutional structures are being questioned in sports, too. “Men make a lot of money from endorsements, from sponsorships, from commercial activities and franchise cricket. That’s where probably the biggest buck is,” Mumtaz said. “All the years that I played cricket I actually put in money as opposed to getting back or getting paid.”

Pakistan and Bangladesh plan to launch women’s professional leagues next year, bringing women a step closer to groups like the Indian Premier League for men, which has drawn players and profits to the sport.

They would also highlight inequality in professional sports, including limited female coaching roles, media coverage, investment and opportunities for advancement.

Across industries, merit is not always enough to overcome incumbent advantage.

In a survey of 2,000 people across Asia by recruiter Hays, 60 per cent said leaders had a “bias toward hiring” and promoting “people who look, think or act like them.” Many studies have shown that female and minority candidates’ odds improve when recruiters use anonymous résumés and that diversity correlates with business performance.

This article is from Nikkei Asia, a global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective on politics, the economy, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and outside commentators from around the world share their views on Asia, while our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of 300 of the biggest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside Japan.

Subscribe | Group subscriptions

Until equality comes — whether in the 151 years forecast by the World Economic Forum or sooner — women are reaching for it in their advocacy and daily work.

As cricketer Alam put it, “I have to set a benchmark for the next generation.”

(This story is part of a series themed around women and wealth in Asia.)

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on December 7 2022. ©2022 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved