Almost three years after the pandemic began, legendary American fashion house Oscar de la Renta has still not made a return to New York Fashion Week. One show was streamed on a more humble platform — Amazon.com.

“Is Amazon exactly the right venue for luxury fashion? I’m not sure,” chief executive Alex Bolen says in a video interview from the brand’s headquarters in midtown Manhattan. “But we have to experiment with new ways to get our story out.”

That shift is emblematic of the challenges and scaled-back ambitions facing many small and medium-sized fashion and luxury names that have been unable to come back from the pandemic as forcefully as sector leaders such as LVMH and Kering.

For Oscar de la Renta, the pandemic was a test of survival. “There were days when I thought we are just not going to make it,” Bolen recalls.

He says 2019 had been a good year for the company: “We’d grown, we were profitable and, importantly, we opened late in the year our first store in Paris” — which Bolen hoped would draw in Chinese tourists. Pre-orders for the pre-fall collection creative directors Laura Kim and Fernando Garcia had shown to buyers in December had been robust. “Fast forward 60 or 90 days, and suddenly everything started to come apart,” Bolen says.

Just as fabric for the pre-fall collection arrived, department stores shut and cancelled their orders. Factory closures meant fabric could be neither cut nor sewn. “Between lost business and owing money to vendors and landlords, I estimated we had about a $25mn hole in the balance sheet,” Bolen says. By the end of March, all but 27 of Oscar’s 300 staff had been put on furlough. “We decided not to pay our landlords and delayed payments to our vendors and had fights with everybody,” says Bolen. “We had to focus on the durability of the business.”

The company pulled through thanks to a $15mn loan and government support but laid off about 50 employees. The $4,000 cocktail dresses and $6,000 evening gowns that are the brand’s bread and butter were offloaded to outlets and sold for “20, 25 cents on the dollar”, Bolen says. “It was awful.”

He says the company has no intention of returning to New York Fashion Week. Instead, it plans to experiment with off-season shows like the one it hosted with Saks Fifth Avenue last August to raise funds for the League to Save Lake Tahoe. In addition to tickets, it generated half a million dollars in clothing sales. These shows — to be held in LA, Palm Beach and the Dominican Republic next year — will be focused not on department store buyers and press — “I don’t think the fashion press at a fashion show is particularly relevant [to us any more],” Bolen says — but on clients.

“Our industry has a problem with keeping up with the Joneses,” he continues, citing Dior’s recent show in Egypt and Saint Laurent’s spring/summer 2023 show across from the Eiffel Tower in September. “I have no business spending that kind of money on a fashion show to sell clothes.”

Bolen’s views on shows parallel his broader views on the business: he is less focused on competing for market share with Europe’s big luxury brands than on running a resilient, profitable business. After falling 65 per cent in 2020, he says sales are on track to reach $120mn this year — “nicely above” 2019 levels. More importantly to Bolen, profit margins have grown from “about 10 per cent” to nearly 25 per cent.

First-time customers tend to come to Oscar de la Renta for bridal, and then start to buy into the rest of the range. “The idea of us chasing after competitor brands that have leather goods businesses or beauty businesses or both, it’s just been a mistake,” he says. “We want to go a different way.”

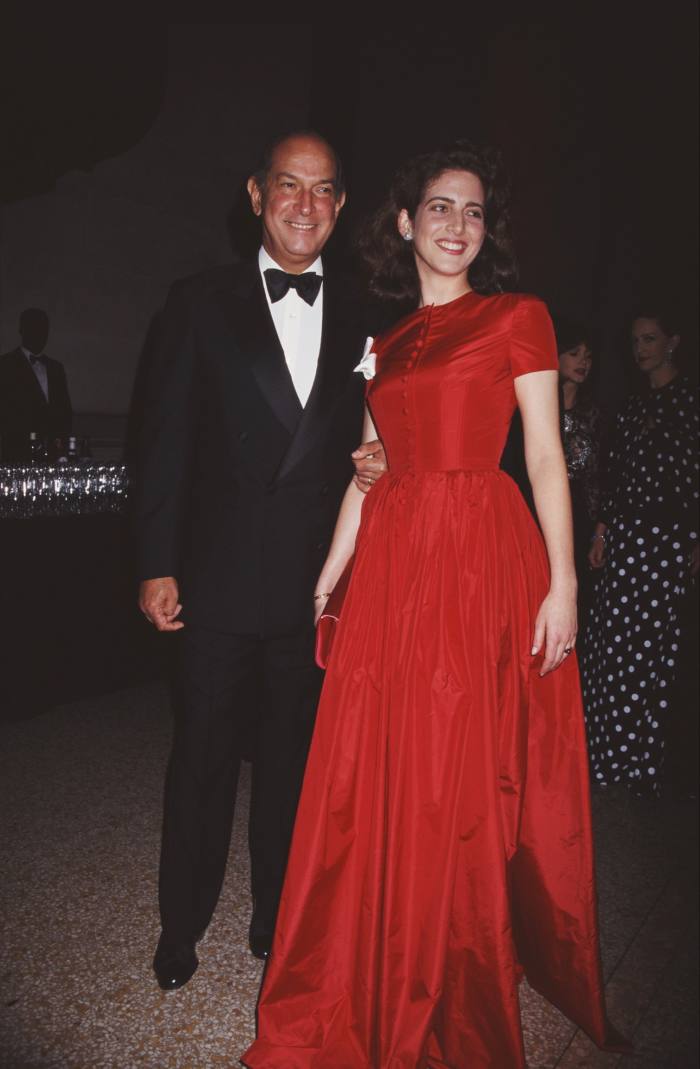

The designer Oscar de la Renta was born in Santo Domingo, in the Dominican Republic, in 1932. A student of art, he learnt to drape and sew at Cristóbal Balenciaga’s salon in Madrid and later at Lanvin under Antonio del Castillo in Paris before opening his own house in 1965 in New York. He soon became the de facto designer of Fifth Avenue socialites and White House matriarchs, outfitting nearly every first lady from Jacqueline Kennedy to Michelle Obama (Hillary Clinton was a friend and eulogised the designer at his memorial service). His later success on the red carpet, in particular with Sarah Jessica Parker in her Sex and the City heyday, made him an international star.

Before he died of complications from cancer in 2014, de la Renta wanted to ensure his name and business would not dissipate in the manner of his former rivals Bill Blass and Halston but, like the great fashion houses of Europe, live on.

The task of carrying on both name and business fell to de la Renta’s stepdaughter and executive vice-president of his company, Eliza Bolen, and to her husband Alex Bolen, a Bear Stearns alumnus whom de la Renta made chief executive in 2004. It also fell, for a time, to designer Peter Copping, whom de la Renta had recruited from Nina Ricci to be his successor and who worked alongside de la Renta in the last months of his life. Copping departed only two years later, and the collections have since come under the direction of Kim and Garcia, who worked under de la Renta and have given a more youthful spin to his classic and decidedly feminine DNA without casualising the brand.

When Bolen joined Oscar in 2004, the company was operating in what he previously described to me as “a kind of designer 1990s licensing model, where the high-end runway product was not the driver of the business, but was very much a promotional tool”. While larger rivals such as LVMH, Kering and Michael Kors were aggressively expanding their leather goods offerings, Bolen decided to streamline the licences and make high-end women’s ready-to-wear the core of the business.

Whether that was the right move is debatable. While leather goods and, in some cases, beauty are now the main profit drivers for luxury companies, few US brands have been able to succeed at the former, which analysts attribute to the lack of long-term investment available to labels in that country.

At the same time, businesses without those profit sources lately find themselves unable to compete on stores and brand awareness campaigns in fast-growing markets such as China. They also lack the resources to deepen relationships with top-spending clients through the carousel of shows, dinners and trips.

The feeling of being unable to compete with the big players has persuaded more than a few family-owned luxury businesses to sell to a conglomerate or private equity firm over the past decade — among them Versace, Missoni and Etro.

Would Bolen consider a sale given, as he says, his sons are not interested in succeeding him? “We get some calls from time to time,” he replies. “In the depths of Covid, I was thinking, wouldn’t it be nice to be part of a big conglomerate? . . . But there’s a lot that we can do on our own.”

Sign up to the Fashion Matters newsletter, Thursdays

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram