Elliott Management backstopped a multibillion-dollar debt package to fund its takeover of television ratings provider Nielsen, helping steer the $16bn acquisition through markets that have grown warier of riskier deals.

The New York-based firm bought the debt alongside other investors at a discount from Wall Street banks, who had agreed to underwrite the highly leveraged takeover when it was first struck in March, according to people familiar with the matter.

The purchase last month comes just weeks after Elliott spent $1bn of its own capital buying junk bonds tied to its takeover of software maker Citrix Systems, the people said.

Elliott’s decision to buy the debt leaves it more exposed to the fortunes of Nielsen, a company whose core business helps advertisers measure their reach on cable channels and streaming networks. The debt comes on top of the $5.2bn in equity that Elliott, along with Brookfield Asset Management, have already injected into the deal.

Credit markets seized up earlier this year, with fears of higher interest rates and the prospect of a recession hitting stocks and bonds. Banks, which had agreed to finance dozens of mega-buyouts by private equity firms during more benign conditions, remain on the hook for the cash on the terms they struck when agreeing to underwrite the deals.

That has left the banks having to sell the debt packages to investors at steep discounts, given the sharp rise in interest rates. Yields on single-B rated debt — a marker of the leverage common in buyouts — have surged from 4.7 per cent at the start of the year to 8.9 per cent, according to ICE Data Services.

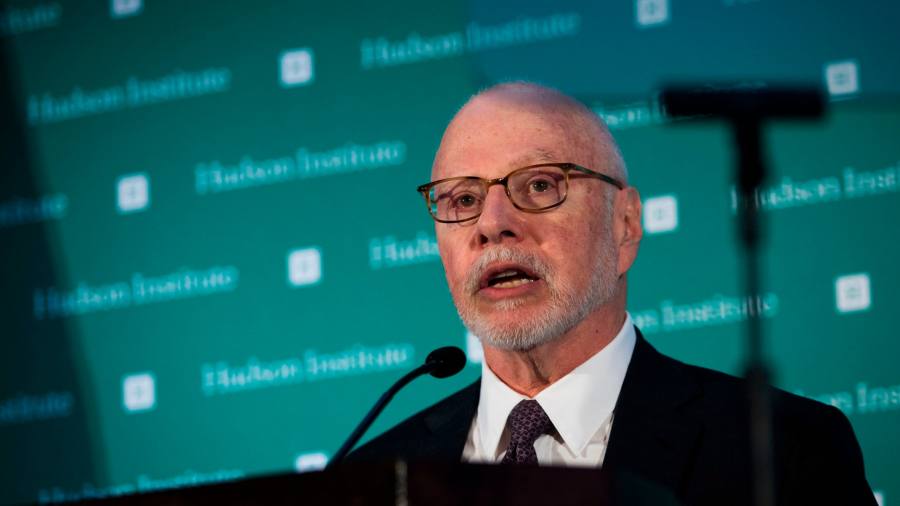

Elliott, one of the best known activist hedge funds, has over the past decade transformed itself into a mammoth asset manager competing regularly with private equity giants like Apollo and Blackstone. Led by Paul Singer, Elliott draws on one global pool of capital, giving it the flexibility to make equity and debt based investments. It also participates in everything from restructurings to leveraged buyouts.

Elliott declined to comment.

The group’s purchase of the bonds tied to Nielsen underlines the group’s appetite for junk-rated debt.

It has also eased the burden on the deal’s more than dozen underwriters, led by Bank of America, as they have tried to drum up interest in the debt. The banks were forced to use their own cash to fund the takeover in October when the transaction closed.

But in November, as credit markets showed some signs of thawing, they started to offload the debt to investors. The banks completed a $1.96bn bond sale for the deal, selling the debt with a coupon of 9.29 per cent. A discount on the bonds lifted the yield on the single-B rated notes to 11 per cent, according to people briefed on the matter. That was more than 1.5 percentage points higher than the yield available on similarly rated debt.

The banks subsequently raised a further $2.4bn, split across US dollars and euros. Demand from investors was strong enough to increase the $1.5bn dollar portion to $2.1bn. A steep 11 per cent discount on the dollar portion and an interest rate 5 percentage points above the floating interest rate benchmark helped attract investors. The yield in the end topped 12 per cent.

The $1.96bn of bonds, which mature in 2029, have rallied since they were initially sold, changing hands on Monday at 97 cents on the dollar.

As part of the takeover, Elliott invested its own cash and rolled over 16.6mn shares for majority ownership, while Brookfield injected $2.65bn into the deal as preferred equity. Brookfield’s preferred stake — which is convertible into a 45 per cent common equity stake in Nielsen — initially made it senior to Elliott, but the purchase of debt will give the latter added rights as a creditor.

“The take-private transaction increases Nielsen’s leverage significantly and pressures its cash flow generation due to the high interest burden,” Jawad Hussain, an analyst with S&P Global, said.

The higher yields on risky debt used in buyout deals has drawn investors, particularly as banks offer steep discounts as they rush to clean up their balance sheets before the year ends. Banks were selling so-called hung debt tied to the $16.5bn takeover of Citrix at steep discounts last week.

But even with the improvement in markets, lenders remain saddled with tens of billions of debt on their balance sheets from buyout deals. That includes the $12.7bn of bonds and loans they underwrote for Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter.