One thing to start: How Sam Bankman-Fried blurred lines between FTX and Alameda. In an interview with the Financial Times, the former billionaire admits that he was more involved in investment and financial decisions at the nominally separate trading firm than he has previously suggested.

Welcome to FT Asset Management, our weekly newsletter on the movers and shakers behind a multitrillion-dollar global industry. This article is an on-site version of the newsletter. Sign up here to get it sent straight to your inbox every Monday.

Does the format, content and tone work for you? Let me know: [email protected]

Asset managers pour money into tech platforms

Wall Street investment banks have talked boldly about becoming technology firms, but it seems like BlackRock went out and did it.

Just as Amazon developed cloud technology for its own needs and then commercialised it, BlackRock built the Aladdin portfolio management system to manage its own holdings and started offering it to clients in 1999, Brooke Masters and I explore in this article.

Now the world’s largest money manager makes nearly 8 per cent of its revenue from selling technology services to parts of the sector. So far this year, its tech division has brought in more than $1bn from more than 950 clients and revenue has kept on growing even as falling markets hit fees from its core investment business.

Meanwhile rival money managers including State Street and Amundi are seeking to emulate BlackRock’s success by creating direct competitors to Aladdin.

BlackRock, State Street and Amundi all argue that the fact that their hands on experience with using the software will make their products especially to attractive asset managers who want to cut costs, simplify their IT and cut the time wasted on repetitive tasks.

But the newer entrants think the shift to cloud-based software has created an opening for new players. They also hope to win clients who feel uncomfortable buying crucial technology from their very largest competitor.

“What we saw was a demand for someone new, not a tech firm, not a classical provider who had been there for 40 years,” said Guillaume Lesage, who heads Amundi Technology. It calculates that at least €1.6bn in annual revenue is up for grabs just from banks and asset managers that need to replace their technology in the next few years.

Michael Eakins, chief investment officer at Phoenix Group, one of the

UK’s largest savings and retirement businesses, which uses Aladdin, said: “The way things are progressing, BlackRock is going to end up being the Bloomberg of financial data. Kudos to them, they’re becoming a tech company.”

Does Aladdin’s unparalleled scale create possible conflicts of interest? Email me: [email protected]

The hunt for the next market fracture

After a decade of falling interest rates and central bank largesse, global financial markets are facing a reckoning, writes Eric Platt in New York.

Soaring inflation is being met by rising interest rates, the slowing of central bank asset purchases and fiscal shocks, all of which are sucking liquidity, the ability to transact without dramatically moving prices, out of markets.

Violent, sudden price moves in one market can provoke a vicious loop of margin calls and forced sales of other assets, with unpredictable results.

“The market is so illiquid and so erratic and so volatile,” Elaine Stokes, a portfolio manager at Loomis Sayles, said. “It’s trading on every impulse and we can’t keep doing that.”

Policymakers are paying close attention to market plumbing and financial stability risks, with the vice-chair of the Federal Reserve last month warning a “shock could lead to the amplification of vulnerabilities”.

Disparate shocks — like the closure of the nickel market in London, structured product blow-ups, the bailout of European energy providers or the rapid pensions crisis in the UK sparked by turmoil in the country’s government debt prices — are being scrutinised as oracles of wider dislocations to come.

Don’t miss our analysis on financial instability, in which my colleagues look at some of the areas that investors are keeping an eye on, ranging from US Treasury market illiquidity to dysfunction in Japanese government debt.

Meanwhile there are concerns about the long-term health of the commercial property market. Exhibit A: Blackstone has limited withdrawals from its $125bn real estate investment fund following a surge in redemption requests. Here’s FT Alphaville on how one of the fastest-growing, most lucrative corners of the Blackstone real estate juggernaut has become a quiet concern to some investors and analysts. And this is why it’s not a redux of the summer of 2007.

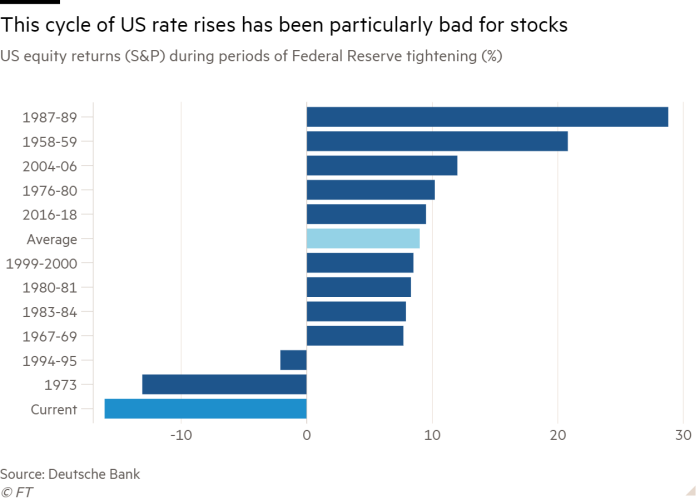

Chart of the week

A year ago Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell called time on an entire era of super-cheap money that began after the 2008 financial crisis. Investors are still learning to live with the reality of higher interest rates and low returns for the long haul, as markets editor Katie Martin and I explore in this Big Read.

Some investors have a bleak outlook for the coming years. “We’re now going through a period which is payback time,” says Nick Moakes, chief investment officer at the £38.2bn Wellcome Trust, one of the UK’s largest endowment funds. He goes on:

“We’ve borrowed future returns, we’re going to pay them back now. The key thing is to make sure we’re in a position in our portfolio to cope with an extended period of sub-par returns because we’ve had this extraordinary period since 2009. Whereas in the last decade we delivered real returns of 11 to 12 per cent a year after inflation, delivering 1 per cent real returns a year after inflation over the next decade would not be an implausible outcome.”

10 unmissable stories this week

Former UK health secretary and chancellor Sajid Javid has held talks with investment house Pimco about his career after politics. Javid held preliminary discussions with Manny Roman, Pimco chief executive, and Andrew Balls, the group’s chief investment officer for global fixed income.

‘It just kinda went crazy’: How Sam Bankman-Fried’s crypto group FTX showered employees with perks before collapsing into bankruptcy. A circle of senior executives in their late twenties and early thirties splashed millions of dollars on everything from travel to sport sponsorship deals and luxury homes.

British companies are braced for a battle with shareholders over boardroom pay after record bonuses were given to executives this year despite a mounting cost of living crisis for many of their workers.

Investors need a different playbook for 2023, writes Jean Boivin, head of the BlackRock Investment Institute and former deputy governor of the Bank of Canada. A new regime of greater macro and market volatility is here to stay.

Doesn’t anyone do due diligence any more? Theranos and FTX show a broad failure by investors to ask enough questions before handing over cash, argues Brooke Masters in this column.

Investcorp is buying US private credit manager Marble Point for about $200mn as the Bahrain-based investment manager significantly boosts its presence in US credit markets at a time of higher interest rates.

DWS has named Blackstone veteran Paul Kelly global head of its €126bn alternatives business, as the Deutsche Bank-owned asset manager seeks to accelerate growth in the business, notably in private debt.

Singapore’s Temasek has launched a review of its $275mn investment in FTX as the state-owned investment fund is scrutinised over the due diligence it performed before backing Sam Bankman-Fried’s crypto exchange.

Lloyds Banking Group’s pension scheme sold billions of pounds of assets to meet collateral calls during September’s market crisis, one of the biggest known sell-offs by a corporate plan.

The Financial Conduct Authority has proposed sweeping changes to democratise investment in financial products, in an effort to help millions of people facing a sharp rise in living costs earn better returns on their savings. Here’s an explainer about the proposals. But the head of AJ Bell, one of Britain’s largest investment platforms, thinks they are the “wrong solution” to the problem of British savers hoarding cash.

And finally

A new exhibition at The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York argues that the interiors created by female fashion designers are freighted with meaning. The show, Designing Women: Fashion Creators and Their Interiors, focuses largely on women working from 1890 to 1970. Its curator Patricia Mears’s interest was piqued by the large number of women involved in the interior design profession at its conception, in the late 19th century, at the height of the Belle Époque.

Thanks for reading. If you have friends or colleagues who might enjoy this newsletter, please forward it to them. Sign up here

We would love to hear your feedback and comments about this newsletter. Email me at [email protected]

Recommended newsletters for you

Due Diligence — Top stories from the world of corporate finance. Sign up here

The Week Ahead — Start every week with a preview of what’s on the agenda. Sign up here