Just weeks ago at the company’s headquarters, Haruo Naito, the 74-year-old chief executive of Japan’s Eisai, was feeling vindicated after almost four decades of trying to develop an Alzheimer’s drug.

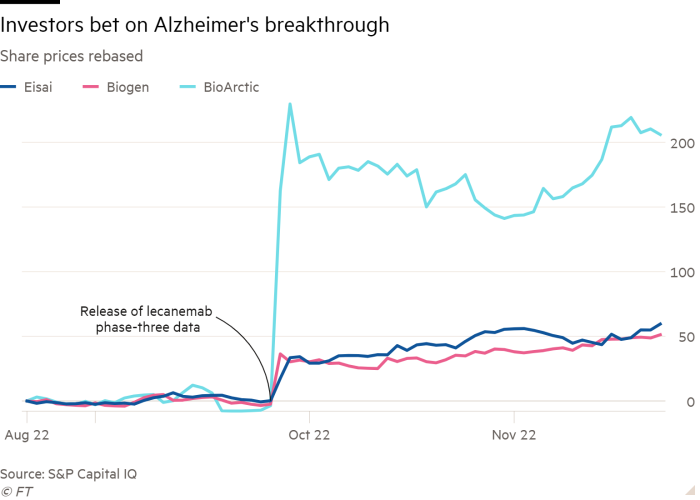

Ahead of the release of detailed information on Eisai’s new drug lecanemab, developed with Biogen, the company’s share price surged 60 per cent after results of a late-stage clinical trial showed that it slowed the progression rate of the memory-degenerating disease.

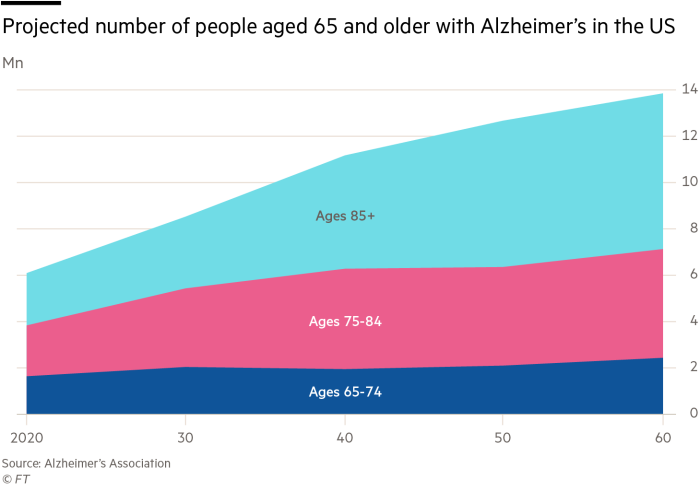

But on the eve of the presentation on Tuesday, news of a second death during trials emerged. That sent Eisai’s shares down 11 per cent, threatening to overshadow what Naito had hoped would be a convincing set of data to settle a debate among researchers about what causes the illness, which affects roughly 50mn people worldwide.

Initial results published by Eisai in September raised hopes of a new treatment for a disease that pharmaceutical companies have spent billions of dollars over several decades researching, only to be disappointed by repeated failures. There has been no major medical breakthrough since Eisai’s Aricept, the most widely prescribed treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, became available in the US in 1997.

At the centre of the debate among scientists is the so-called amyloid hypothesis, which holds that Alzheimer’s is primarily caused by the build-up in the brain of a sticky plaque called beta amyloid. But dozens of drug trials — including the latest by Swiss drugmaker Roche — have failed to prove clearing the plaques can slow the rate of cognitive decline.

Both Roche’s gantenerumab and lecanemab, co-developed by Eisai and Biogen, are monoclonal antibody treatments based on the hypothesis. But unlike many other drugs being developed, lecanemab specifically targets amyloid-beta aggregates called protofibrils.

“I think it is safe to say that the results have proved that the condition will improve by removing the amyloid-beta aggregates,” Naito, the grandson of Eisai’s founder, said in an interview held before the death of the second patient was disclosed. “With lecanemab as a beginning, we are feeling increasingly confident that we can develop the next Alzheimer’s drugs, one after the other.”

If the theory were proven, Naito said lecanemab could open the path to research on other neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s. It would also breathe new life into rival amyloid-reducing drugs in development such as donanemab, an antibody being developed by Eli Lilly.

Investors are betting that Eisai, a $20bn pharmaceutical company still little known outside of Japan, can succeed where many larger companies have failed. When it published lecanemab’s topline results in September, BMO Capital Markets concluded the trial amounted to a first “clean win” in the battle against Alzheimer’s disease.

Evan Seigerman, a BMO analyst, said that depending on the level of access granted by US national insurance schemes, Medicare and Medicaid, as well as other countries’ healthcare schemes, “we could see end-user peak sales at more than $13bn”.

Some scientists have expressed caution about reading too much into topline results, which show lecanemab reduced the rate of cognitive decline in early-stage patients by 27 per cent compared with a placebo after 18 months. They said it was critical that Eisai and Biogen present full trial data and publish their findings in a peer-reviewed journal to rebuild confidence in amyloid-targeting Alzheimer’s drugs following recent failures.

The botched launch last year of aducanumab — the first amyloid-clearing drug to win approval and the first new treatment for the disease in almost two decades — has heightened concerns. Questions about its effectiveness and the robustness of two late-stage clinical trials, as well as a sky-high launch price of $56,000 a year, have led clinicians and US payment authorities to shun a treatment that was co-developed by Eisai and Biogen.

“The lecanemab study is the first trial to achieve a robust, statistically significant difference between drug and placebo — so that’s a huge achievement,” said Rob Howard, a professor of old-age psychiatry at University College London.

But he added that the clinical significance of the slowdown in progress of Alzheimer’s caused by lecanemab was “trivial” in terms of noticeable change in a patient, raising the question of whether the drug is worthwhile given potential side effects that include brain bleeds.

Medical authorities are investigating the deaths of the two patients during lecanemab’s trials to determine if they were linked to the treatment, according to a report by the journal Science.

Eisai said it could not comment on individual cases because of patient privacy. It added that all available safety information indicated the therapy was not associated with “an increased risk of death overall or from any specific cause”.

“The benefits are still really unclear,” said Howard, who would like Eisai to provide much more detailed information about the lecanemab trial during the presentation on Tuesday. “I want to see a proper breakdown of the data in terms of the efficacy.”

Experts are divided on whether the trial results prove the amyloid hypothesis.

Andrea Pfeifer, chief executive of AC Immune, a clinical-stage company developing drugs targeting neurodegenerative diseases, said the results validated amyloid beta as “a target for Alzheimer’s disease therapies”. But she said it might not be the only target for Alzheimer’s and future treatments could require different combinations of therapeutics, each targeting specific neurodegenerative disorders and inflammation of the brain.

Alberto Espay, a professor of neurology at the University of Cincinnati, said in addition to lowering amyloid levels in the brain, lecanemab increased the levels of a normal protein, amyloid beta-42, which could also be the cause of the benefits highlighted by the trial.

For Eisai and those affected by Alzheimer’s, however, lecanemab is a breakthrough they have been chasing for a quarter of a century.

“I’ve met with dementia patients and their families many, many times and they ask me each time when the next drug will come out,” said Naito.

Following the publication of trial data, he apologised for the long delay in developing lecanemab. Nonetheless, the drug represents a major coup for Eisai, a company dwarfed by rivals such as Roche and Eli Lilly. It licensed lecanemab in 2007 from a small Swedish biotech, BioArctic, which it continues to work closely with on research.

Lars Lannfelt, BioArctic’s founder, told the Financial Times that Eisai had proved a strong partner and lecanemab’s successful trial should help the company expand thanks to its royalty agreement with Eisai.

“We are very optimistic . . . and of course we are hopeful lecanemab will be approved,” he added.

To make up for its small scale, Eisai has partnered with larger peers, such as Merck and Biogen, to develop drugs. It has also narrowed its focus on two therapeutic areas: oncology and neurology.

“Everyone says it must be tough to develop a drug for dementia, but for Eisai this is a disease that we know most about, even more than cancer,” Naito said.

Under Naito, who took over as president in 1988, the company’s 11,000 employees have spent 1 per cent of their working hours — two and a half days a year — engaging with Alzheimer’s patients and their families. “It’s not by coincidence that our trial results were successful,” Naito said. “There has been a large amount of learning from our past failures.”

One of its biggest setbacks was the disastrous launch of aducanumab, which prompted the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to severely restrict reimbursement for all amyloid-reducing monoclonal antibody treatments. Eisai in March gave up its right to share the profits from that drug, whose benefits appear limited.

“The big lesson for us was to ensure transparency of data,” Naito said, referring to the controversy over whether the trial data of aducanumab provided enough evidence that the drug really worked.

“I don’t think there will be such a controversial debate this time since there is only one Clarity AD clinical trial for lecanemab so it is a very simple and easy to understand drug development.”

Regarding the potential price for lecanemab, Naito expressed confidence that US insurers will be willing to pay for the drug.

“There is no point unless the drug reaches the patients and is administered, so our biggest priority is to make sure the drug reaches the patients that need it,” Naito said. “The basis of our pricing policy will be that it will be at a level that is affordable.”