Mass global job cuts at Meta, Twitter, Stripe and other technology giants are bitter news for their staff in Dublin, coming just before Christmas. But analysts said they are a “wake-up call” for the side effects of Ireland’s over-dependence on big tech.

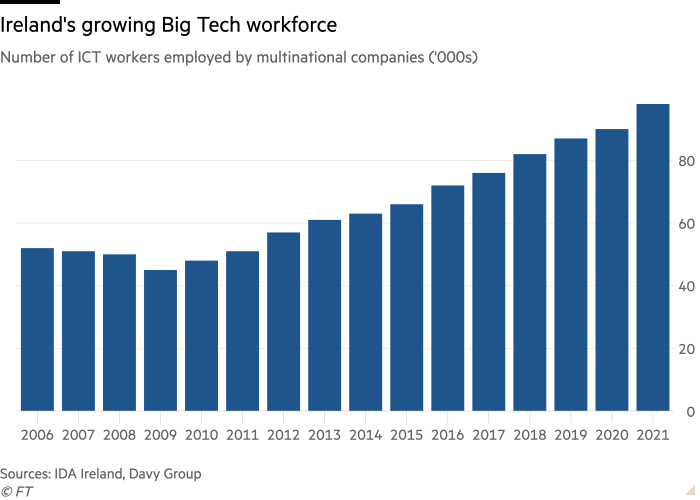

Ireland’s decades-long gamble on global IT has paid off in investment, jobs and billions of euros in taxes paid by the multinationals who have their shiny European headquarters in the Irish capital’s Docklands and employ 12 per cent of the capital’s workers, according to stockbrokers Davy Group.

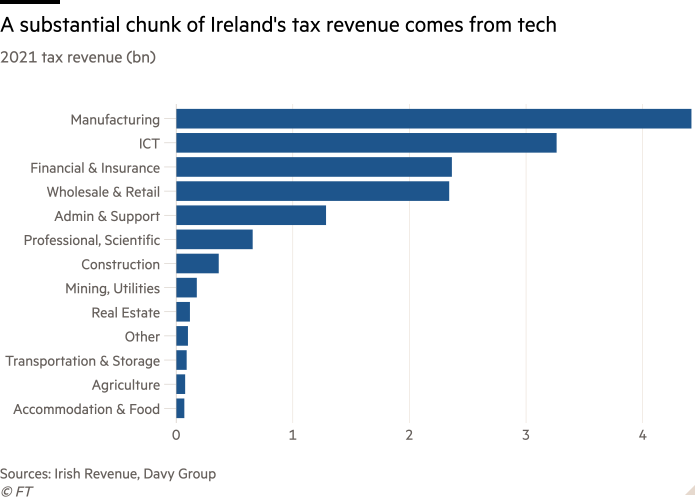

Big tech’s performance has helped supercharge Irish growth and their extraordinary corporate tax revenues — despite Ireland’s baseline rate for businesses being just 12.5 per cent — have given the government a deep fiscal cushion to tackle current cost-of-living pressures.

With Meta sacking 13 per cent of its global workforce, Elon Musk cutting Twitter’s headcount by half and Stripe, the payments company founded by two Irish brothers, letting go of 14 per cent of workers, the tech bubble of the past decade may have burst as companies that expanded fast now face a rising cost of credit.

The short-term hit will mean hundreds of jobs are lost in Ireland. Yet some here believe less reliance on the industry may be no bad thing for a country sometimes dubbed Europe’s “Silicon Valley”.

“Ireland really bet the farm on the future of tech . . . almost at the expense of everything else,” said Mark O’Connell, executive chair and founder of OCO Global, a trade and investment focused advisory firm. “It’s not pleasant for people who are losing their jobs . . . but for other sectors that have been eclipsed by this, I think it can be maybe a good rebalancing.”

A tech slowdown could also ease upwards pressure on wages, fuelled by huge employment growth in the sector, economists said.

Ireland has added 24,000 new jobs in the information and communications sector since the first quarter of 2021, as the country hit record employment levels. The purchasing power of highly paid tech staff has driven up rents in a market where housing supply was already under severe pressure.

“The reality is that this is a necessary correction for a really overheating economy,” said Danny McCoy, chief executive of employers’ confederation, IBEC.

He called Ireland’s housing crisis and overstretched public services “a real function of the imbalance in the economy”. If some of those things “start to cool down now, that’s actually a positive sign that we might be getting back to more normality,” he added.

Unlike when computer maker Dell moved a factory from Ireland to Poland in 2009, axing 1,900 jobs, the cuts this time will not crater the economy.

But Jean Cushen, associate professor of human resource management at Maynooth University, said the dismissals were “a wake-up call”.

“If these companies do decrease investment and if we are entering into a tech winter, there are not necessarily other sources of growth and sectors of growth,” Cushen said.

The coming cuts, expected to amount to no more than 1,000 jobs in Ireland, have also spooked the government, which has warned for months that it cannot rely forever on the tax from tech giants precisely because that bonanza could one day vanish.

Big tech and pharma multinationals make up more than half of corporate tax revenues, which at nearly €14bn in the nine months to September were almost €6bn ahead of the same period last year. Ireland has agreed to join a new global minimum 15 per cent corporate tax rate, although it is not clear when this will take effect.

Conall Mac Coille, chief economist at brokerage Davy, said Ireland was battling a housing supply crunch even before the tech downturn.

“I don’t think the tech sector slowing down is going to cure Ireland of these capacity problems,” he said. “On balance, the news is more negative than positive . . . but it’s not catastrophic so far.”

Tech workers, who account for some 6.5 per cent of all jobs in Ireland, contribute 10 per cent of the income tax revenues, according to the finance ministry. But no firm has announced it is shutting up shop in Ireland and Mac Coille noted that most are still expecting revenue growth.

As negotiations over dismissals kicked off in companies across Dublin, Dell announced a €2mn investment in an existing centre for customers to test-drive new technologies in County Cork.

Mark Redmond, chief executive of the American Chamber of Commerce Ireland, also noted that the job cuts news coincided with the announcement of 520 new jobs in tech in Ireland.

Patrick Walsh, founder and chief executive of Dogpatch Labs, a Dublin-based innovation hub and home to Ireland’s national start-up accelerator, NDRC, said the current crunch offers another opportunity: to give homegrown tech the same laser focus as Ireland has previously trained on big tech.

“In the 1980s, amid recession, high unemployment and emigration, we dropped our corporation tax from 40 per cent to 12.5 per cent. This, combined with a low-cost base and a highly educated, English-speaking workforce, started to attract foreign direct investment,” he said.

“It was not the wrong call. However, the reality is that the Ireland of today has an unbalanced economy with concentration risk and an economic vulnerability as a result,” added Walsh, who is also a member of the National Competitiveness & Productivity Council. “We created the number one fiscal policy environment in the world if you’re a Google, but we lag behind when it comes to key start-up policies.”

Redmond said OECD research showed a “spillover” of talent from multinationals to Irish companies. Job cuts at big tech meant “lots of great talent is now back on the market, which can actually be good for business”, said one senior HR consultant in Dublin, although she added her investor clients did not expect conditions to pick up “any time soon”.

Ireland is bracing to take its share of the tech job cutting pain ahead. “The bigger issue is if revenues begin to flatline, or decline,” said Paddy Cosgrave, co-founder of Web Summit, a technology conference. “That would impact both jobs and tax revenues in Ireland.”