This article is an on-site version of our Energy Source newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Tuesday and Thursday

Hello and welcome back to Energy Source.

The COP27 climate talks in Egypt have entered their final week. The presidents and prime ministers have largely come and gone. It is now down to lower-level ministers to hash out an agreement.

Expectations are low. No bold new climate targets are likely and prospects for a significant breakthrough on funding for poorer countries to deal with climate change look remote.

Still, talks between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping at the G20 summit in Indonesia have lifted hopes the two superpowers might grind out a last-minute climate deal in Sharm el-Sheikh, our colleagues Aime Williams and Demetri Sevastopulo reported.

Today’s newsletter focuses on a particularly thorny aspect of US-China energy relations: US efforts to break its reliance on China’s dominant solar manufacturing base amid evidence it is entangled in Beijing’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

It sits at the intersection of many of the countries’ disagreements, from trade to human rights to climate change. A new report argues the solar industry is not moving nearly fast enough to extricate itself from the situation.

In Data Drill, Amanda looks at a multibillion-dollar effort by G20 countries to help wean Indonesia off coal.

Thank you for reading and I’d be interested to hear what ES readers think: is the solar industry doing enough to address alleged human rights abuses in its China supply chains? Let me know at [email protected]. — Justin

Can solar kick its China addiction?

The solar industry has a China problem.

More specifically, it has a Xinjiang problem. The industry is deeply dependent on panels and raw material produced from China’s western region where the United Nations has documented a sprawling system of arbitrary detention, forced labour and other human rights abuses by the Chinese government targeting ethnic Uyghur people.

The solar industry is not doing nearly enough to extricate itself from the Xinjiang despite the mounting evidence that its supply chains are enmeshed in these abuses, argues a new report called Sins of a Solar Empire from the Breakthrough Institute, an environmental think-tank.

“A much more aggressive effort is needed to diversify the global solar supply chain and invest in new manufacturing capacity outside of China to displace this unethical production,” said Seaver Wang, the report’s lead author.

“We’re talking about people [in Xinjiang] who are coerced away from their families and are not allowed to return, they’re paid next to nothing, forced to work incredibly long hours and in hazardous conditions . . . these are people waiting for the world to take action,” Wang said.

The report has landed during the COP27 climate talks, which have focused on the slower than needed expansion of clean energy, and just after US president Joe Biden and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping held their first face-to-face meeting as heads of state. Those talks produced an apparent thaw in relations as both sides said their joint climate change discussions would resume after being frozen for months amid worsening bilateral relations.

The US solar industry’s main trade group, the Solar Energy Industries Association, says it has urged its members to shift their supply chains out of Xinjiang and has set up “track and trace” protocols to ensure supplies are not linked to human rights abuses in the region.

But breaking with China has proven difficult for the industry. Beijing has lavished tens of billions of dollars in cash and subsidies on the domestic solar manufacturing sector over the past decade, building a juggernaut in the solar supply chain.

A recent International Energy Agency report found that 40 per cent of global polysilicon manufacturing, a key industry input, comes from Xinjiang province alone, including a single plant in the region that turns out 14 per cent of the world’s output. More than 85 per cent of solar cells are made in China and more than 95 per cent of solar wafers. The IEA called the concentration of solar manufacturing in China a “considerable vulnerability” for the industry.

Yet China’s rise to dominance in the solar sector has also delivered a spectacular decline in manufacturing costs, which has made solar power among the world’s cheapest sources of electricity and supercharged the industry’s growth — an undeniable win in the climate fight.

It raises the prickly question of whether rapidly diversifying the solar supply chain away from Xinjiang will slow the urgently needed energy transition.

In addition to the solar manufacturing incentives, the US Congress last year passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act last year, which blocked US imports of solar panels that have suspected links to human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

That disruption to the supply in panel supplies, however, has been blamed for contributing to the slowdown in solar installation in the US this year, underscoring the industry’s challenge in quickly undoing its dependence on China.

Wang says there does not need to be a trade-off. The report argues that industry cost declines have mostly come from “technological advances, public-private investment, and industrial policy that can be replicated elsewhere”, rather than forced labour.

Even if costs end up being slightly higher as the industry rebuilds its supply chains outside of Xinjiang, the industry should not “shy away from it”, he adds.

That will be put to the test in the next few years as the US moves aggressively to pull solar manufacturing back from to its own shores, or at least friendlier countries’ shores.

The Inflation Reduction Act, passed earlier this year, includes generous incentives to build new solar manufacturing capacity, and process key minerals, in the US. Enphase, First Solar and SPI Energy are among the companies that have laid out new domestic US solar manufacturing plans since the bill was passed, a huge reversal after years of defections from the US, largely to China.

“I think the US is on the right track to really lead by example,” says Wang — but is still not moving quickly enough. And Europe has been even slower to end its reliance on Chinese solar supplies.

It leaves Wang “largely pessimistic” about the solar industry’s efforts so far to move out of Xinjiang given the lack of alternatives and short-term cost advantage of sourcing from China.

There is still an “acceptance of the status quo”, said Wang, and an “unwillingness to move away from the very cheap, solar commodities that you can produce if you source from the Xinjiang suppliers”. (Justin Jacobs)

Data Drill

The G20 summit kicks off in Indonesia today with a spotlight on the host country’s clean energy transition. The US, Japan, and other developed countries announced a $20bn partnership to help Jakarta phase out the use of coal and roll out renewables.

The partnership known as the Just Energy Transition Partnership follows an $8.5bn commitment last year from western countries to help South Africa decarbonise, and comes amid a clamour from developing nations for “loss and damage” funding to adapt to the climate crisis at the ongoing COP27 summit. Commitments to Vietnam, India, and Senegal are also expected in the coming months.

“This is an important next step in getting a major emitter like Indonesia on a trajectory for the electricity sector that’s more aligned with 1.5C climate targets,” said Jake Schmidt, strategic director of international climate at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

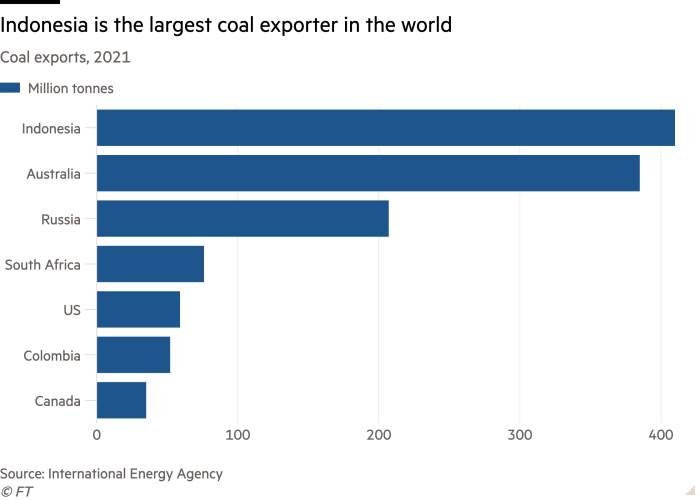

Indonesia is the world’s largest exporter of coal and the third-largest producer, and the fossil fuel makes up about two-thirds of its electricity generation capacity.

Climate advocates cheered the announcement but cast a wary tone when it comes to ensuring the money is distributed in a just and accountable way. Despite the billions of dollars South Africa received last year, much of the money remains unspent.

“The JETP will only fully be deemed a success if the political statement and investment plan actually deliver the transformational public and private financing required to pivot to a clean energy system,” said Camilla Fenning, programme leader at international climate think-tank E3G. (Amanda Chu)

Power Points

Energy Source is a twice-weekly energy newsletter from the Financial Times. It is written and edited by Derek Brower, Myles McCormick, Justin Jacobs, Amanda Chu and Emily Goldberg.

Recommended newsletters for you

Moral Money — Our unmissable newsletter on socially responsible business, sustainable finance and more. Sign up here

The Climate Graphic: Explained — Understanding the most important climate data of the week. Sign up here