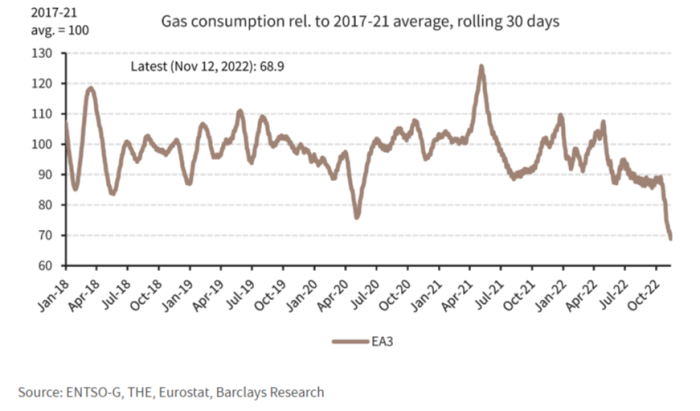

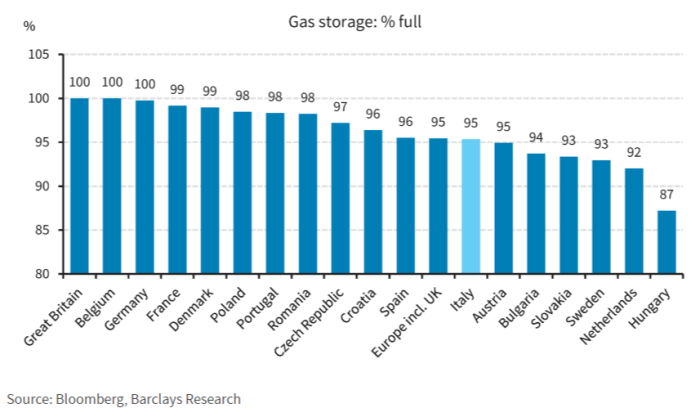

Nice out, isn’t it? Europe’s unusually mild winter has been the stroke of luck needed to preserve gas supplies, with consumption about 30 per cent below the seasonal average and storage full in Germany and France.

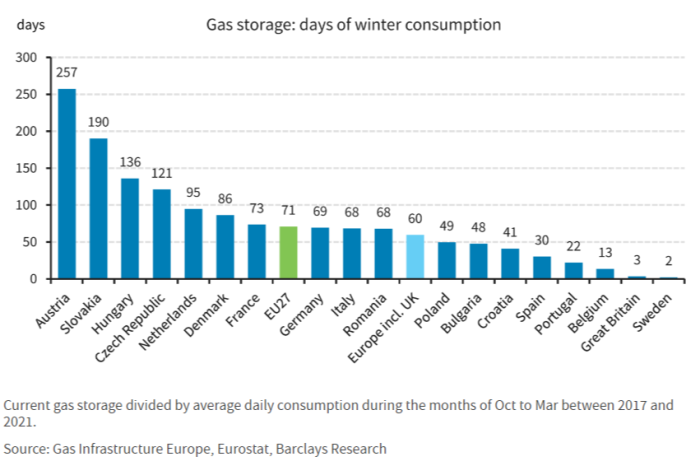

Charts below and throughout are via Barclays analysts Mark Cus Babic and Abbas Kahn:

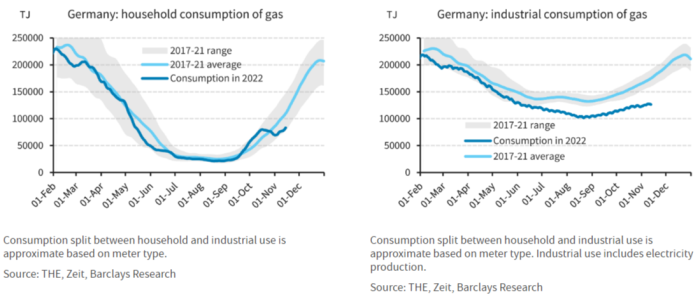

It’s a combination of industrial demand being crimped and domestic consumption suddenly dropping well below the average in October. The trends for Germany are typical for Europe as a whole:

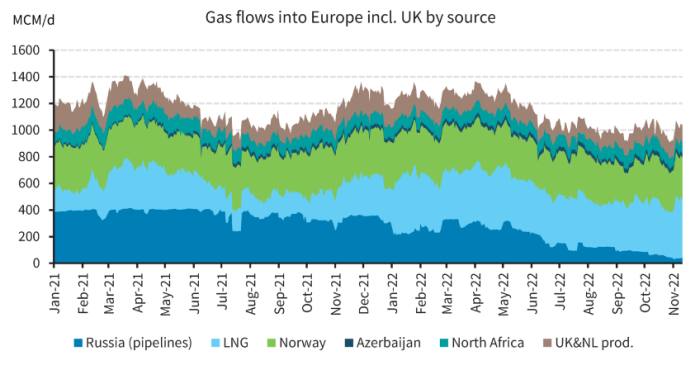

Warm weather buys time for Germany, which is building two new liquefied natural gas terminals. The floating storage is due to come online in the next few months in preparation for the complete shutdown of Russian supply.

But there’s no mileage in an empty tank. Europe may be temporarily awash with LNG but the market remains tight, prices remain well above historical norms and a supply shortfall is still likely by next year. How might Germany get what it needs?

To answer that question and a few others we caught up with Rui Soares, of independent investment firm FAM Frankfurt Asset Management, whose work on Russian gas dependence we published in May.

Most LNG contracts are long term. Where are new supplies going to come from?

“Germany needs to tap about 3 per cent of the world’s annual LNG production to fill up its new terminals. One way is through savage capitalism. Most LNG contracts are long-term but suppliers may not comply with the terms, pay a penalty for breach of contract, and sell the LNG to the highest bidder. German industry is able to bid high.

“Trafigura and Glencore, which trade about 6 per cent of all LNG worldwide, are very opportunistic. And Germany only needs half of the LNG they trade.”

Does that mean a European bidding war to hijack each other’s supplies?

“Some EU countries have more LNG contracted than they consume. They can re-sell the excess. For example, Spain has an LNG storage capacity of 70bn cubic metres [BCM]. But it only consumes 36 bcm annually. Enagás [of Spain] has more than 36 bcm contracted annually through long-term LNG contracts but sells the excess on the spot market. Nobody knows exactly how much, but 10 bcm alone would already account for two-thirds of Germany’s needs. Shipments can easily be diverted.

“This also explains why the EU has passed legislation in June making it mandatory for all member countries to fill their gas storage sites to at least 80 per cent of capacity by November 1. Tanks are full, trading of excess nat-gas is effectively halted, and EU members are primed to redistribute supplies as needed.”

But isn’t the problem also tight supply?

“Although conventional wisdom holds that there is no additional LNG production capacity worldwide, this is actually not the case. Some nat-gas producers, particularly those in the Gulf, may not be entirely transparent. The suspicion is that they have additional production capacity but do not report it.

“For example, after the Fukushima accident in March 2011, Japan increased its nat-gas consumption by 20-25 bcm in 12-18 months. The dominant view at the time was that there would be no additional short-term LNG production capacity available worldwide, and that Japan would have to divert LNG away from other countries. Yet production met the incremental demand and the additional supply was largely from Qatar.”

What about shipping?

“At the end of 2019 there were 584 LNG carriers worldwide. By the end of 2021 there were 700, an increase of 20 per cent. It’s possible that the new ships are smaller but LNG production and export between 2019 and 2021 only increased by 6.5 per cent.

“On top of that, the global order book for new LNG carriers stands at 140-150 units, with Russia supposedly accounting for 20-30 of those. Between a fifth and the quarter of the order book is delivered each year. A capacity crunch looks unlikely.”

What happens if the new terminals aren’t completed on time?

“Things are much better now than they looked in May. The EU natural gas storage targets have been hit early.

“In terms of the maths, Germany’s nat-gas consumption before the Ukraine war was around 100 bcm per year, versus storage capacity of around 23 bcm.

“Industry accounts for approximately 35-40 per cent of consumption and is cyclical. Less than 15 per cent is for electricity generation. The remainder is demand from households and the service sector, with four-fifths of their consumption happening during the winter months. It’s therefore reasonable to estimate that Germany’s nat-gas consumption during the winter months is approximately 50 bcm.

“Germany imports 55 bcm of non-Russian gas per year through its pipeline system. Deliveries are reasonably constant, amounting to roughly 18 bcm during the winter months. Add this to existing storage and Germany will have around 40 bcm of nat gas available, suggesting without the new tanks it would need to reduce consumption by around 20 per cent for the numbers to add up.”

That sounds like a lot.

“German industry has already reduced consumption by more than 20 per cent through efficiency measures, production shutdowns and fuel switching. Households could make the same savings by lowering their thermostats by approximately 3 degrees Celsius, or perhaps less once oil stoves, electricity heaters and even fireplaces are taken into account. This would mean German households living with a room temperature of between 17 and 19 degrees Celsius. Hardly an unbearable sacrifice.

“And if the terminals are up and running then even this sacrifice could be avoidable. Cutting a long story short: it will be a less pleasant winter than usual in Germany, but households will not freeze nor will industry collapse. Reality is better than perception.”