This article is an on-site version of The Lex Newsletter. Sign up here to get the complete newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Wednesday and Friday

Dear reader,

COP27 will seem like a talking shop to many. To me, any dealmaking on future energy supply is of overriding significance. As an Italian, I come from a country wrestling with the prospect of a dismaying shortage of power. And as a frequent flyer, I have a carbon footprint that is unenviably large.

I, therefore, have a strong personal interest in how the world can balance short-term security of supply with long-term decarbonisation.

Europe needs to increase liquefied natural gas imports to wean itself off Russian gas. These will support the economy and reduce the incentive to burn coal. The US is the obvious source of this gas.

But anyone who believes the US will divert plentiful, cheap gas to Europe is deluding themselves. This has been “agreed” by US president Joe Biden and European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen only at the level of energy diplomacy. Existing US liquefaction capacity is finite. The LNG it produces has either been sold in advance or will go to the highest bidder.

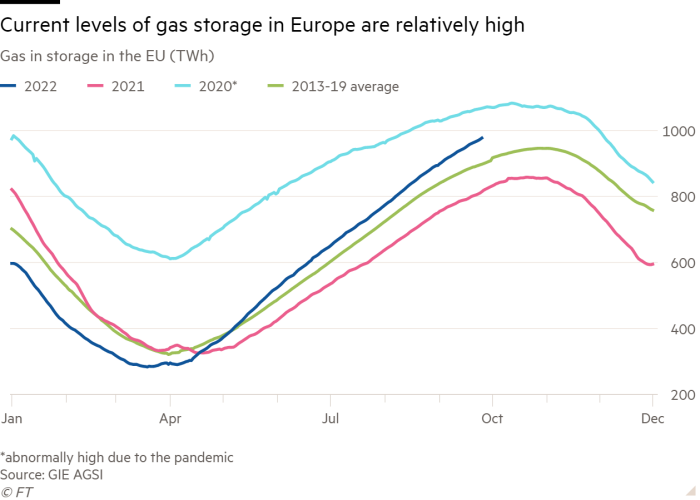

True, Europe has been importing a lot more LNG in 2022 — an extra 50bn cubic metres by year-end. That goes some way towards filling the 80 bcm gap left by Russian supply outages.

Of the increment, about 30 bcm will come from the US, as a progress report from the US and EU task force on energy security suggests. But Europeans have no cause to thank US politicians for supporting them in their cold war with the Russian foe. Europeans have wrested the gas from consumers in Asia — where demand has fallen 8 per cent in the year to date — at a high cost.

Next year looks even tighter. Russian gas supplies declined only gradually over the course of 2022. If they stay at the current depressed levels, Europe will need to increase LNG imports in 2023. But there is precious little new capacity coming onstream.

In 2022, there were two start-ups of US LNG facilities, Sabine Pass and Calcasieu Pass. These have a target of 13mn tonnes per annum, less than 20 bcm. Meanwhile, an outage at leading US liquefaction facility Freeport took — well guessed! — 13 mtpa out of the market.

Bidding war

With limited additional capacity, Europe will need to bid high to reroute LNG from other areas of the world. That will drive up prices and destroy demand.

Supply was always going to be tight. What is surprising is that construction of new facilities has not picked up more.

The US is building some liquefaction plants for a delivery date of 2025-2026. But the ones that are already under construction are insufficient to fuel growing Asian economies and replace Russian supply to Europe. New projects for about 80 to 90 mtpa (or 120 bcm) are needed, according to Bernstein estimates. And these need to win approval quickly. Even the speediest projects take three years to build.

However, only two new plants were given the go-ahead in 2022 — Cheniere’s Corpus Christi 3 and Venture Global’s Plaquemines — for 35 bcm. The rest, it seems, are still working on their business plans.

One big sticking point is putting long-term off-take contracts in place for future capacity. Those are needed to get project financing in place.

You’d think buying gas in the US to sell into Europe would be quite an attractive proposition, given EU gas prices are more than four times those in the US today. Utilities are not queueing up because Europe is fraught with political uncertainties and doubts over the speed of the energy transition.

Severe steer

Policymakers are certainly signalling a hard change of tack. If one adds up the impact of all the renewables and efficiency ambitions contained in the RePower EU manifesto, gas demand is expected to fall sharply to 2030 — absorbing all of the Russian shortfall and plenty more besides.

In this context, it would take a brave European utility to commit to 20-year gas contracts. But that does not help get projects approved for the near-term requirements that clearly exist. And that is even before one considers whether European ambitions are likely to be achieved.

The bottleneck is likely to be worked through over time. Already, big operators such as Shell and Trafigura are stepping into the void. They are providing long-term contracts in hopes of selling gas into Europe first, and then into Asia if Europe really starts succeeding with its green transformation.

Meanwhile, there are ways in which Europe could both justify new, long-payback fossil infrastructure and keep its colours pinned to the decarbonisation mast.

Investing in carbon capture technologies, which can remove the carbon dioxide from fossil fuels and store it underground, is an obvious way to reconcile the two. Europe may also have to recognise that not all the assets it invests in will be used to their full potential for their full foreseeable life. Write-offs will be the cost of an energy transition that runs in lumps and bumps, rather than straight lines.

Tight gas markets are bad for the world’s near-term carbon footprint. That alone makes unlocking LNG capacity a good topic for all those bilateral talks at COP27.

To comment on this or any other aspect of Lex, please email me at [email protected].

Enjoy the rest of your week,

Camilla Palladino

Lex writer

If you would like to receive regular Lex updates, do add us to your FT Digest, and you will get an instant email alert every time we publish. You can also see every Lex column via the webpage

Recommended newsletters for you

Cryptofinance — Scott Chipolina filters out the noise of the global cryptocurrency industry. Sign up here

Free Lunch — Your guide to the global economic policy debate. Sign up here