For the past few months, a fierce debate has been raging over the question of what exactly is behind the sudden, sharp exodus of older British workers into economic inactivity. Is it driven by rapidly worsening health or, more benignly, a flow of early retirements?

There are two further, key questions here. First, where does one draw the line in determining whether ill health played a role in someone’s decision to leave the labour force? And second, is it preferable to have a trend of worsening health that drives people out of the workforce, or one that spares the working but condemns the already workless to stay put?

One thing, though, is clear: the UK is now roughly three years into a steady march of chronic illness that is scything through the most vulnerable and marginalised in our population.

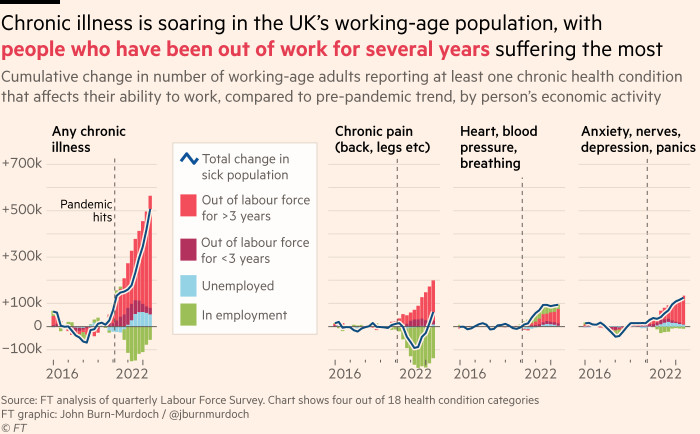

Beginning shortly before the pandemic but then accelerating, there has been a steep climb in rates of chronic ill health among the long-term workless. Today there are half a million more working-age people in the UK with impairing health conditions than if pre-pandemic trends had continued, and 90 per cent of them are people who have not worked in several years.

And the damage is by no means limited to the older cohort. Rates of chronic back and neck pain have risen among the over-50s, but there has also been a clear increase in mental health difficulties among the under-35s.

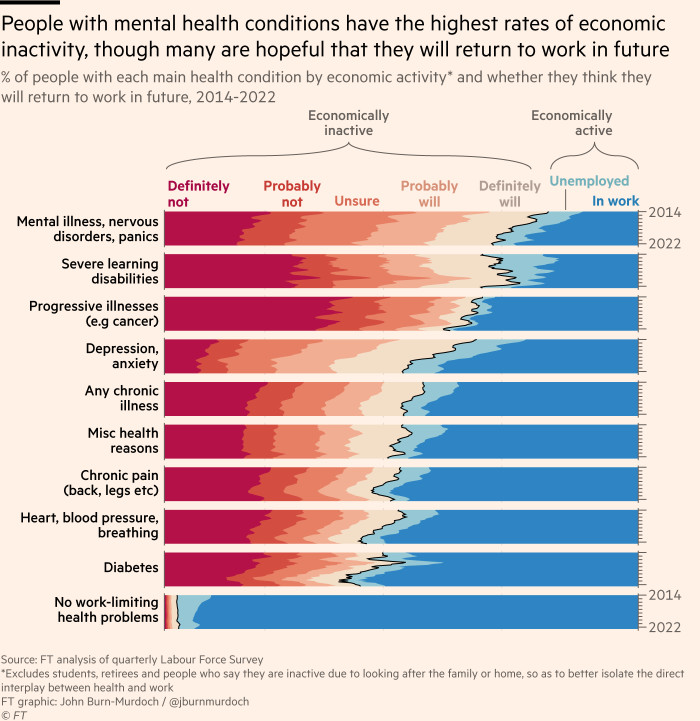

Economic activity rates are lower for Britons with mental health problems than for any other condition. Seventy per cent are outside the workforce, and only half of those say they will probably or definitely work again.

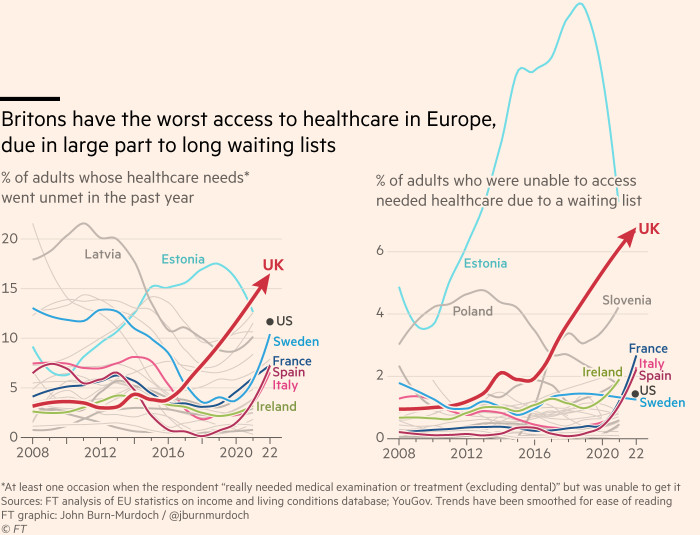

The data, while not conclusive, suggest a dynamic in which those whose position on the periphery of society had already exposed them to greater health risks suddenly found themselves high and dry when access to healthcare was curtailed, and are now some way down ballooning waiting lists.

This week, the NHS announced that the length of its waiting list for hospital treatments has probably been overstated due to some patients being on it for multiple treatments. There may in fact be “only” 5.5mn people waiting for potentially life-changing treatment. Among them are 1.3mn people who have been referred to mental health services but are yet to receive their second contact.

The international perspective is striking. Over the past year, one in six UK adults has had a pressing need for medical examination or treatment and been unable to get access, with almost half of these cases due to the length of waiting lists. This is the highest figure out of 36 European countries and almost triple the EU average.

With a lengthy recession looming and spending cuts on the agenda, the future for Britain’s peripheral class looks bleak, but bringing them back into the fold should be the country’s top priority.