Joe Biden wants US oil companies to boost production. Two powerful forces are working against the president’s call.

Wall Street wants oil groups to shower billions in profits on investors rather than spend freely on new supply. And the International Energy Agency has warned oil demand will peak by the middle of the next decade, undercutting the case for massive new investment.

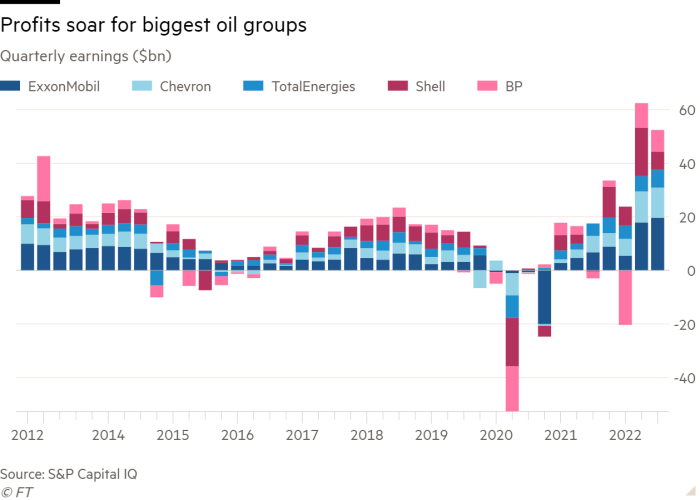

These tensions were on display in the past week as ExxonMobil and Chevron reported net profits that over the past two quarters added up to the biggest in their histories.

The two US oil supermajors said they would funnel cash towards shareholders in the form of higher dividends and share buybacks. They did not say they would spend more to raise production.

Goldman Sachs has argued that the sum of these decisions, echoed at smaller oil companies in the US shale patch, will be a long period of oil prices above $100 a barrel. West Texas Intermediate crude settled at $90 a barrel on Wednesday.

Biden on Monday accused oil companies of “war profiteering” after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and threatened them with new taxes if they did not accelerate output. “I think they have a responsibility to act in the interest of their consumers, their community and their country to invest in America by increasing production and refining capacity,” the president said in a speech.

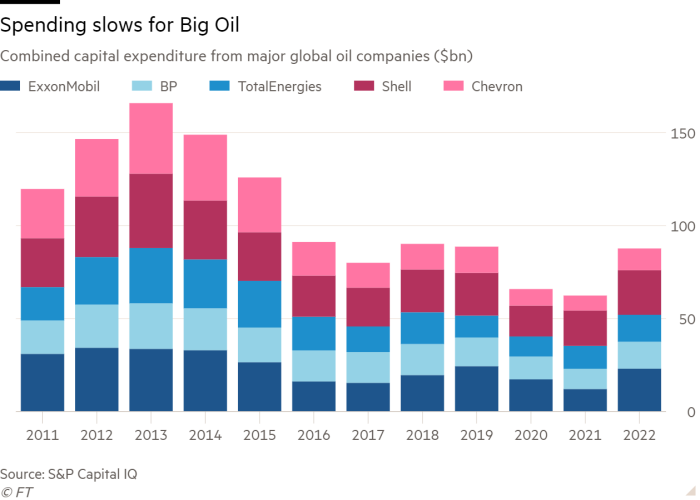

But investments by US supermajors, which remain more committed to their core oil and gas businesses than their European rivals, are down about 30 per cent compared to their plans before the pandemic.

Exxon in 2019 said that it planned to spend $30bn to $35bn a year on its business, but now is aiming for about $23bn a year. Chevron had signalled annual capital expenditures of roughly $19bn to $22bn before the pandemic but now envisages $15bn to $17bn.

Both companies will update spending plans in December, but neither said they planned to raise medium-term targets when asked by the Financial Times last week. Chevron aims to raise oil and gas production by 3 per cent a year and Exxon about 2 per cent a year, coming largely from investments made years ago.

Pavel Molchanov, analyst at Raymond James, said: “Oil companies could drill more, but they do not want to because their shareholders have pushed them to invest less and instead pay more dividends and share buybacks — and their shares in many cases are at all-time highs.”

Exxon shares have risen 79 per cent this year even as the broader S&P 500 index has fallen 21 per cent. It is a remarkable turnround from a company that 18 months ago lost a landmark proxy fight, in part over what activist investor Engine No. 1 said was excessive spending from the oil supermajor.

Chevron is up 52 per cent in 2022. “The signals from our investors don’t suggest they want to see more investment in production,” chief executive Mike Wirth told the Financial Times last month.

Darren Woods, Exxon’s chief executive, last week defended the company’s heavy spending on dividends at a time of high fuel prices for consumers.

“There has been discussion in the US about our industry returning some of our profits directly to the American people. In fact, that’s exactly what we’re doing in the form of our quarterly dividend,” he told investors after Exxon reported quarterly net profit of $19.7bn.

Independent US shale producers, which over the past decade delivered much of the world’s oil supply growth, are also holding spending steady. Scott Sheffield, CEO of Pioneer Natural Resources, last week told analysts his company’s “low reinvestment rate” would “moderate oil production growth” but generate free cash flow that could be paid out to shareholders.

Just days before the industry’s latest bumper profits, the IEA said for the first time it saw “definitive” signs that oil demand would peak under current government policies. It said crude demand would likely grow at less than 1 per cent a year before peaking in 2035, although it still forecast that demand would remain elevated to 2050.

Wirth and other oil executives say investors do not want them to invest in part because of policies and rhetoric in the US and Europe aimed at shifting the economy away from fossil fuels to fight climate change.

“The mood music matters,” Wirth said. “When you ask investors, do you want me to take the cash that could come back to you, and instead let me put it back into this business that policymakers have said they want to see go away? Investors say, ‘oh, I’ll take the cash’.”

Despite the slowdown in expected consumption, the IEA said the industry would still need to plough roughly $470bn a year into oil and gas production projects this decade to keep up with demand, about 50 per cent more than in recent years.

Goldman Sachs has argued that “structural supply under-investment” across the oil industry could underpin a sustained period of $100-plus crude prices even if the economy slows.

The market may need “ever rising oil prices in coming years given the reluctance to invest in oil during the energy transition”, the bank’s analysts said.

Additional reporting by Derek Brower in San Ramon, California

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here