The widening performance gap between public and private markets is a huge topic these days. Investors are often seen as the gormless dupes falling for the “return manipulation” of cunning private equity tycoons. But what if they are co-conspirators?

That’s what a new paper from three academics at the University of Florida argues. Based on nearly two decades worth of private equity real estate funds data Blake Jackson, David Ling and Andy Naranjo conclude that “private equity fund managers manipulate returns to cater to their investors”.

This is not an entirely new suggestion. Academics (and some practitioners) have boggled for years over why investors seem willing to pay extra for illiquidity, completely contrary to what financial theory and common sense would seem to suggest.

For example, a 2014 paper examining the impact of fair-value accounting on European private equity found that it increased correlations to public markets and hurt European LBO fundraising. In 2017 the chief investment officer of the Idaho pension system apparently dubbed the lack of volatility the “phoney happiness” of private markets.

More recently, AQR’s Clifford Asness argued in 2019 that “big time multi-year illiquidity and its oft-accompanying pricing opacity may actually be a feature not a bug” of private capital (Full disclosure: some journalists have written about this as well.) Since then Asness has been on a campaign to get this called “volatility laundering”.

But Jackson, Ling and Naranjo’s findings are more than just a stylised mental model to explain the popularity of private capital. Their central conclusion is that “GPs do not appear to manipulate interim returns to fool their LPs, but rather because their LPs want them to do so”.

Similar to the idea that banks design financial products to cater to yield-seeking investors or firms issue dividends to cater to investor demand for dividend payments, we argue that PE fund managers boost interim performance reports to cater to some investors’ demand for manipulated returns.

. . . If a GP boosts or smooths returns, perhaps by strategically timing asset acquisitions and dispositions or by misstating the values of underlying assets, investment managers within LP organizations can report artificially higher Sharpe ratios, alphas, and top-line returns, such as IRRs, to their trustees or other overseers. In doing so, these investment managers, whose median tenure of four years often expires years before the ultimate returns of a PE fund are realized, might improve their internal job security or potential labor market outcomes.

Return manipulations can also produce significant paper wealth for LPs. For U.S. public pension LPs, this can marginally improve funding statuses or alter required contribution funding rates. Because PE returns are often quoted in IRRs, such return manipulations can even permanently window dress the PE fund’s end-of-life returns, which possibly protects LP investment managers in bad states.

This probably helps explains why private equity firms on average actually reported gains of 1.6 per cent in the first quarter of 2022 and only some modest marks downwards since then, despite global equities losing 22 per cent of their value this year.

Just to highlight real estate — the main source of data for the University of Florida paper — Blackstone’s giant private property trust BREIT took in $4.2bn in the third quarter and eked out a small gain even as publicly traded Reits lost 12 per cent of their value over the same period.

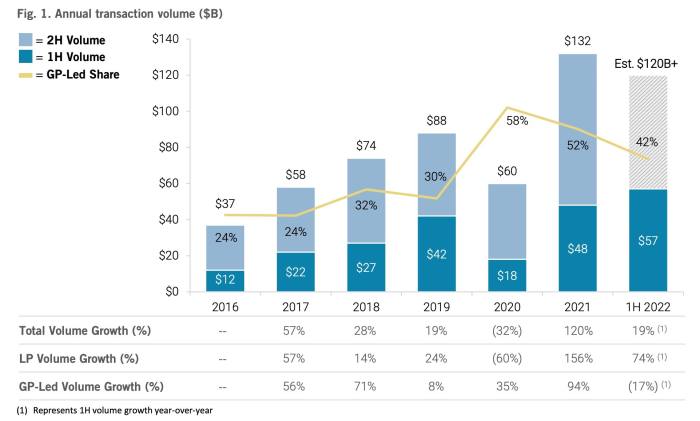

However, the increasingly anomalous accounting values of private holdings gets harder to defend when there is an increasingly active market for trading stakes in private equity funds. A record $57bn worth of fund stakes changed hands in the first half of 2022, according to Jefferies.

Typically, the “secondary” private equity market was where some investors might sell a chunk of one of their investments because their allocations were a bit overweight, they needed to raise cash for some other investment, or the fund stank and they wanted to get out. The stakes therefore usually traded at a discount.

In 2019 the hunger for private equity exposure was so immense that some investors would actually pony up a premium, but in the first half of 2022 the average stake traded at 86 per cent of the fund’s net asset value, according to Jefferies. And yet the reported accounting value of those funds seems remarkably resilient?

This increasingly insane divergence was a big subject in an interesting Q3 letter to investors from Justin Hughes at Phase 2 Partners, a San Francisco investment firm, which someone kindly sent us.

. . . We recently reviewed a 13- page list of private equity interests available for sale through a bulge bracket investment bank. Every single fund on the 13-page list is available at a discount to the manager’s stated value. Smoothed returns that rely on mark to model accounting, we believe, may be leading to an overallocation of assets to private markets. We recently met with a leading private market manager with an interesting view — it was their view that private markets are the new ‘core’ asset class as opposed to public markets. Specifically, we wanted to know how their portfolio seemed to be worth a 40% higher EBITDA multiple than the public markets.

The company explained to us that these are completely different markets — the private markets, the new ‘core’ asset class deserves a premium to their liquid cousin, the public market. Wow, I am old! I immediately went home, pulled out my latest edition of Ibbotson & Associates: Stock, Bonds, Bills & Inflation and ripped up the chapter on liquidity premiums! Starting next month, Phase 2 will issue all of its returns using mark to model! JUST KIDDING!

Maybe investors are just in on the joke, rather than being the butt of it?