When Credit Suisse executives struck a plan to spin off its capital markets and advisory business in the summer, they chose a name that harked back to its 1980s glory days: First Boston.

But as the strategy developed, they soon realised the intellectual property for the brand was already owned by a series of small financial services businesses who refused to sell.

Instead, the bank settled on the name CS First Boston for the business that it plans to list next year as part of a restructuring of the group.

For 166 years, Credit Suisse executives focused on growing the business from its humble beginnings financing Switzerland’s railway network into an international bank offering wealth management and investment banking to a global client base. The 1988 merger with First Boston was part of the Swiss bank’s efforts to grow its investment banking business in the US.

On Thursday morning, that expansion drive came screeching to a halt as the bank unveiled a radical new strategy aimed at arresting years of losses alongside a SFr1.5bn investment by the Saudi National Bank.

By the end of the day, Credit Suisse shares, already battered by years of scandals and churn at the top of the bank, had fallen by 19 per cent.

The plan, devised by the bank’s latest management team, chief executive Ulrich Körner and chair Axel Lehmann, will involve stripping back the business and making it more focused on wealth management and its Swiss domestic market.

“We are creating a new Credit Suisse with a simpler, more stable, more focused business model,” said Lehmann on Thursday.

The expensive restructuring is to be funded by a SFr4bn capital raise, backstopped by the Saudi National Bank, whose investment will make it Credit Suisse’s largest shareholder with 9.9 per cent, based on current holdings.

That deal with SNB, the largest commercial bank in the Gulf country, was poorly received by Credit Suisse shareholders, whose earnings per share will be diluted by around a quarter.

“It’s very painful to give 10 per cent of the bank away for just SFr1.5bn,” said a top-10 shareholder in the group. “Alternatives such as a partial IPO of the Swiss bank would have been better.”

David Herro, chief investment officer of Harris Associates, the bank’s largest current shareholder, was more supportive: “We welcome the aggressive approach Credit Suisse is taking to stabilise and improve the performance of both the investment bank and the group as a whole.”

The retreat from global investment banking and doubling down on wealth management — especially in the Middle East — has raised concern among some shareholders and analysts about the influence of the new Saudi investors and whether the reformed business will be too conservative.

“Certainly radical surgery was needed — but you have to wonder what the new investors want out of this,” said the top-10 shareholder.

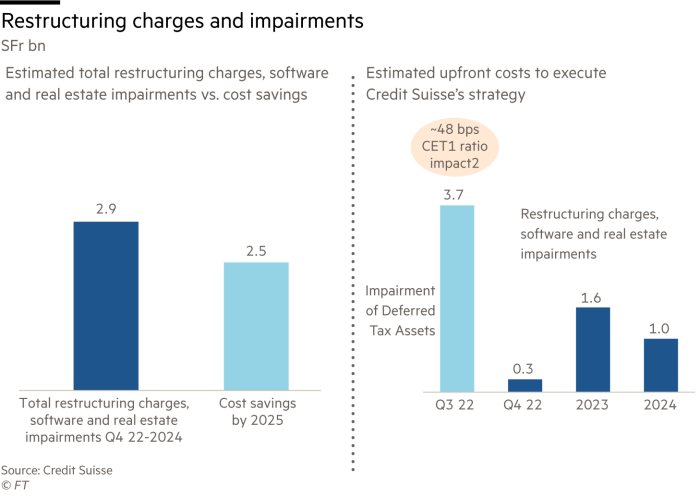

The three-year plan drastically pares back Credit Suisse’s investment bank and involves partially selling off the profitable securitised products business and spinning out CS First Boston. It will also include SFr2.5bn of spending cuts across the business, with thousands of redundancies planned.

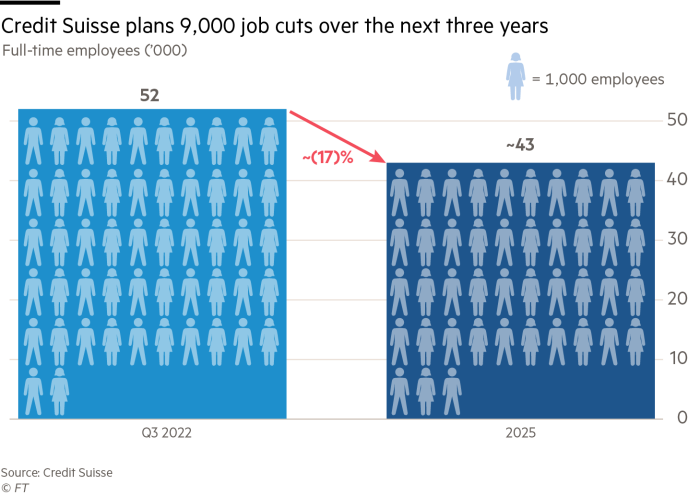

The group’s headcount will drop by 9,000 to 43,000 by 2025, with 2,700 job cuts expected by the end of the year.

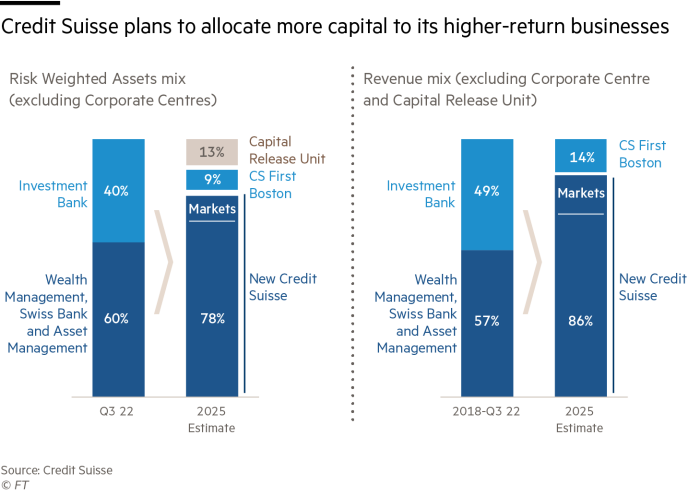

Over the next three years, the bank plans to shift billions of dollars of risk-weighted assets from its investment bank to its wealth management, domestic bank and asset management divisions, which will collectively account for 80 per cent of RWAs and 85 per cent of revenues by 2025.

Analysts greeted the plan with scepticism, especially the company’s conservative medium-term profit estimates, which target a group return on tangible equity of around 6 per cent by 2025.

“Our main concern is . . . the lowly Rote target for 2025, which appears to lack ambition,” said Citigroup analyst Andrew Coombs.

“Part of the rationale for reallocating capital is to drive a re-rating, but this can only go so far if the return prospects remain this low. The stock appears cheap, even post-dilution, but there is likely to be significant execution risk in the coming months, so this remains a high-risk investment.”

One Credit Suisse board member said the conservative approach was a symptom of how many Swiss nationals were running the bank, which has undergone a complete leadership change in the past year, with many senior roles going to former executives of rival UBS.

“That Swissness comes out in the conservative estimates,” they said. “It creates a culture and a way of working that is sustainable and not short-term minded.”

SNB’s involvement also raises questions about the future direction of the Swiss bank. SNB published a statement on Thursday saying the reason for its investment was to work with Credit Suisse on developing asset management, wealth management and investment banking services in Saudi Arabia.

It also said it would explore “strategic partnerships” with the Swiss bank and would consider investing in the spun-off CS First Boston business.

A Credit Suisse executive involved in the discussions with the SNB said Saudi Arabia was a market it was planning to grow in and the SNB investment would help its expansion in the country.

“We have been in the Middle East for nearly 60 years and it will be one of the strongest growth regions over the next 10 years,” they said. “It is a region we have focused on and we want to grow in — especially as we have strong partners in the region.”

Credit Suisse already has two other large Middle Eastern shareholders, the Qatar Investment Authority and Olayan Group, an investment business run by a wealthy Saudi family. Both own about 5 per cent of Credit Suisse stock and bought their initial stakes during the financial crisis.

Despite the wider job cuts, Credit Suisse announced last month that it would expand its presence in Doha, hiring 100 staff and launching a tech hub with Qatar’s Investment Promotion Agency.

The SNB investment is a sign of growing interest from Saudi Arabia in acquiring foreign assets.

Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds from Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait bought stakes in western banks and other distressed assets during the financial crisis, while Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund sat on the sidelines.

But under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who has transformed the PIF into one of the world’s most active sovereign wealth funds since taking over as chair in 2015, Saudi Arabia has become much more aggressive in its approach to investing in western assets, and the recent boom in oil prices has given the country more financial firepower to buy stakes.

SNB was formed by the merger of the National Commercial Bank and Samba Financial Group, which completed this year. Analysts said the merger was partly driven by Riyadh’s desire to create a national champion to develop the financial services sector as Prince Mohammed seeks to project the kingdom as a regional hub. State entities own just over 50 per cent of SNB, with the PIF the largest shareholder.

Though Credit Suisse shareholders said they were apprehensive about Saudi influence on the bank, these concerns were not shared by its senior executives.

“The region is important to us from a wealth perspective, so it’s important to have large investors who are there,” said a person involved in discussions over the SNB investment. “Some other investors may have concerns, but it’s not something we worry about.”

Additional reporting by Samer Al-Atrush in Riyadh and Stephen Morris in London