This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. For a change of pace, nothing about the UK today, despite yesterday’s big news. The pound and gilts are relatively calm, and there are better FT people to cover the politics. In particular, I suggest you have a look at Stephen Bush’s Inside Politics newsletter (one-click sign up here).

Email me: [email protected].

Goldman makes a lot of money, and maybe you should own it

Making fun of Goldman Sachs is one of life’s simple pleasures. Everyone who works there makes a ton of money and acts all important, but what is the point of them? The investment banking and securities trading businesses just harvest the frictional costs of transactions between third parties. In a better world, these businesses would be barely profitable, and Goldman people would be a lot less full of themselves.

So it is good fun to point out, for example, that the bank trades at one times its book value — a dirt-cheap multiple — and that its effort to increase that valuation by getting into retail banking has been an absolute car crash. In the immortal words of Nelson Muntz: ha ha!

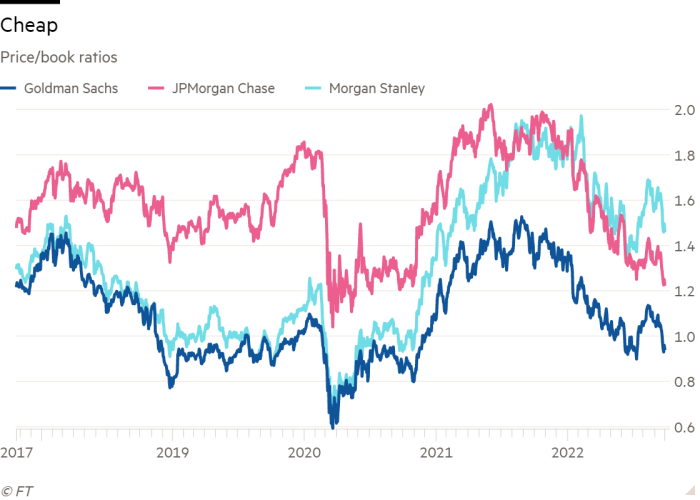

Here is a chart of Goldman’s price/book ratio compared with that of more diversified peers JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley:

There are two reasons that a pure investment bank (or rather mostly pure investment bank with just a little this and that on the side) such as Goldman Sachs gets a lower valuation than one with a wealth management operation (Morgan Stanley) or a retail/commercial bank (JPMorgan Chase). First, the earnings from advisory services, underwriting and trading are cyclical, volatile and hard to predict more than a few months into the future. Investors pay up for steady and predictable. Second, deposit funding can be used for (some) investment banking and trading activities, and it is cheaper than wholesale funding.

But long-term investors should like buying cheap stocks and I think there is a simple case for long-term investors owning Goldman.

One worry is that Goldman’s failure to either build or buy a large diversifying business in wealth management or retail finance is a sign that the company is strategically mismanaged. But this is not necessarily so.

Retail banking is a commoditised business where scale means a lot and Goldman’s strengths mean basically nothing. Maybe the bank was foolish to try it, but it is wise to recognise that it wasn’t working and to pull back. Yes, Goldman would be worth more today if at some point in the past 20 years it had managed to buy, say, a big ETF business such as iShares (BlackRock got it first) or maybe a bank with a big trust or wealth management business such as Northern Trust or First Republic (I have no clue if Goldman has even thought about this). But it is not clear what regulators would allow Goldman to buy. Nor is it clear what it could afford to pay. Other bidders, already big in those businesses, could pay more because they could take more costs out of the combined operations.

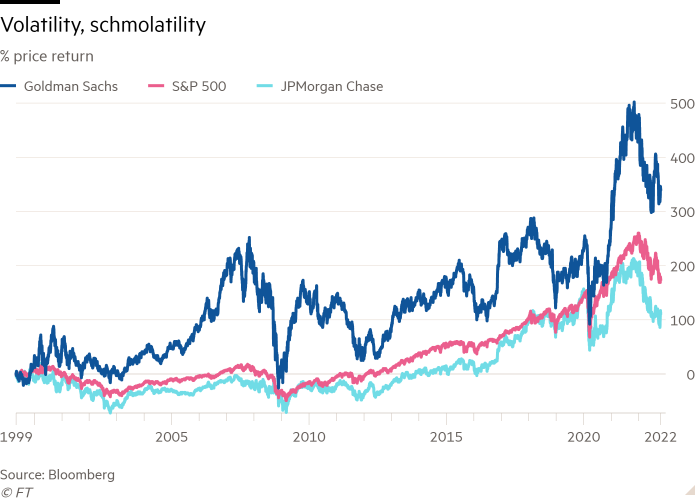

Goldman may be stuck with its low valuation. But judging by history, that need not discourage patient investors. Here is Goldman’s share performance since it IPO’d back in 1999, compared to the S&P 500 and the wonderfully diversified JPMorgan:

Goldman absolutely smokes the market and JP. Even adjusting for dividends, Goldman’s 487 per cent total return is well ahead of JP’s 318 per cent and the market’s 387 per cent. The basic reason for this is that while Goldman’s profits may not be steady, they are big, and they get bigger fast, over time. Between 1999 and 2021, on Capital IQ data, Goldman’s book value grew at 10 per cent a year. That’s fast.

Goldman’s powerful franchise — its position atop markets where the top few companies earn most of the profits — is very valuable. Yes, its profitability is volatile. But one of the most important factors in favour of long-term investors is that for them, volatility is not the same thing as risk. As long as Goldman’s position in the investment banking industry is stable, its investors will prosper over time. Or as Christian Bolu of Autonomous Research puts it, “when the environment is good for what they are good at, they are a monster”.

Of course, Goldman’s position in the industry is not guaranteed. But that position has proven very durable so far, despite lots of effort by competitors and would-be tech disrupters. I noted at the start that in a better world Goldman would be less profitable. Well, I don’t think the world is going to get better any time soon. Not in investment banking, anyway.

As recession closes in, Goldman may get cheaper. Keep an eye on it.

Stocks defy rates. Unhedged is surprised

In the past two weeks, the futures market-implied peak (or “terminal”) federal funds rate — expected to arrive at the March meeting of the US Federal Reserve — has risen by 50 basis points, topping 5 per cent. The yield on the 10-year Treasury has risen 47 basis points, to 4.2 per cent. If you had told me two weeks ago this was going to happen, I would have confidently predicted a very nasty step-down for stocks. That did not happen. The S&P 500 is down all of 3 per cent since October 5. This flies in the face of the idea — to which Unhedged is a paid-up subscriber — that the stock market is all about the Fed right now.

Puzzled, I emailed a bunch of smart market people. Their responses were generally similar, and amounted to (a) yes, this is weird and (b) it has to do with the fact that earnings reports have been strong so far. Here is Bob Michele of JPMorgan Asset Management:

The corporate bond market has also held up very well. There is investor confidence that corporate America is doing well despite higher input costs and financing rates. Businesses seem to be able to pass along the majority of the inflation pressures with only a negligible loss of revenue. Corporate profitability remains very good.

And Greg Peters of PGIM:

It’s a massive, even historic move in front end [rates] — but stocks are holding in due to decent earnings. The equity market is waiting for earnings to weaken to justify the decline in multiples we’ve already seen, so earnings have to truly soften from here to see more stock downside.

Dec Mullarkey of SLC Management adds another wrinkle:

There are two major things going on right now. The Fed is racing to flatten inflation and rate volatility has been elevated. These don’t always travel together and once the end game is in view, in this case the terminal rate, rate volatility should settle down . . . Over the last week both the Vix and Move [interest rate and equity volatility indices] have dropped and that’s helping risky assets.

So: earnings are supportive, and the market sniffs peak rates soonish, even if those rates are expected to be higher than anticipated earlier in the month. Fair enough, so long as we don’t get another big inflation surprise. But to play devil’s advocate: Isn’t anyone else thinking about a recession?

Our clothes are clean enough, apparently

Whirlpool, the appliance maker, reported results last night, and the news was not great. Sales fell 13 per cent year over year, and, in anticipation of weak demand, the company cut production by a third in the quarter. This stock fell hard after hours and is now down over 40 per cent on the year.

More evidence, then, that goods deflation is here. That is positive news if services and wage inflation follow. In the meantime, though, not quite all the news from corporate America is good.

One good read

Alan Beattie has a flinty reading of Biden’s China chip policies.

Recommended newsletters for you

Cryptofinance — Scott Chipolina filters out the noise of the global cryptocurrency industry. Sign up here

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here