As Kwasi Kwarteng prepares his mini Budget on Friday, economists have said one of the main tasks facing the new chancellor is shoring up confidence in the UK economy.

The country has become more reliant on inflows of foreign money this year than at any time since records began in 1955, highlighting its vulnerability to any fall in trust in British economic management.

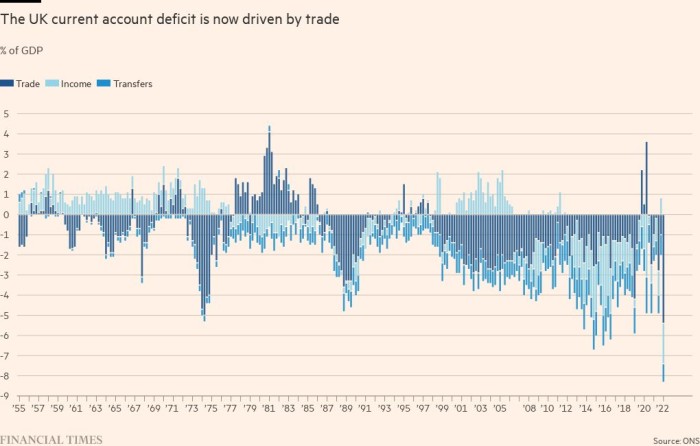

The current account deficit — which includes the UK trade balance and the net income from foreign investment and transfers — deteriorated to a record 8.3 per cent of gross domestic product in the first quarter of this year, as the country’s imports far exceeded the value of its exports.

With such a gap between the country’s consumption and its production, the pound can only maintain its value if foreigners want to lend to Britain or buy up assets such as land, housing or companies across the country.

But if confidence drops, “capital inflows will fall [and] the price of UK assets is also likely to tumble as foreign investors head for the exit”, said Neil Shearing, group chief economist at Capital Economics.

The UK has long run a current account deficit and generally found it relatively easy to finance, except in times of stress, such as the late 1970s when ministers had to go “cap in hand” to the IMF and in 1992 when sterling fell out of the EU’s exchange rate mechanism.

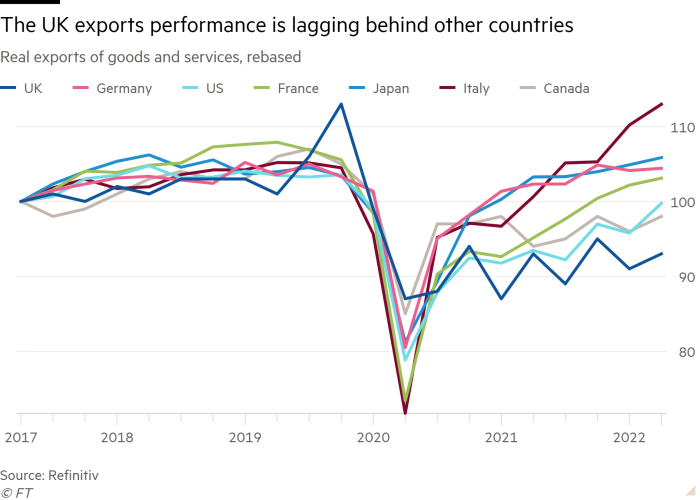

Although the sudden worsening of the deficit was largely caused by the soaring price of energy imports following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the concern underpinning sterling’s recent fall to a 37-year low against the US dollar is that investors will no longer be willing to finance the UK’s excess consumption.

Foreign funding is necessary because the UK’s trade deficit is not offset by other flows of money within the nation’s current account. In the early years of this century, the trade deficit was partly financed by income on UK ownership of assets abroad that was higher than foreign ownership of UK investments.

However, recent data show that net income on investments is negative, as are transfers, such as foreign aid and remittances paid to citizens abroad.

With the current account deep in the red and dependent on foreign funding, the UK needs to be seen as an attractive location for loans or investments.

Simon Harvey, head of analysis at foreign exchange company Monex Europe, said this was a problem because investors were worried about the “government’s ballooning pile of debt”.

Susannah Streeter, senior investment and markets analyst at asset manager Hargreaves Lansdown, said the need for foreign funding also added to pressure on the Bank of England to raise interest rates. “The UK might not be able to attract enough foreign capital to fund its debt at today’s levels of interest,” she said.

An alternative to lending the UK money to finance its consumption of imports is to sell assets to foreigners, which also requires them to buy sterling.

But this was not a long-term strategy, said Ross Walker, chief UK economist at NatWest Markets. The country would become poorer, he said, and it would raise the income flowing abroad from those assets, weakening the current account in future.

“This in turn puts downward pressure on the currency, fuels imported inflation and damages living standards,” he added.

A falling currency is often part of the solution to a gaping current account deficit. Although exports become more competitive, it generally works by raising the price of imports, resulting in consumers eventually buying less from abroad.

To avoid that squeeze on incomes, confidence in the government’s economic strategy is vital, according to Shearing. The strength of UK institutions and the rule of law have meant that the UK “is still an attractive destination for foreign capital”, even with an internationally large current account deficit.

Another advantage for the UK is that other European countries also have deteriorating trade and current account balances, although for most of the last decade the UK has had the largest deficit relative to the size of its economy of any G7 country.

The OECD has forecast that the rise in the value of energy imports will turn Italy’s current account surplus into a small deficit this year, while Germany’s surplus will shrink and France’s deficit will widen. However, none have deficits as large as the UK.

Ultimately, this makes the UK the most vulnerable to a change in sentiment, where taking risks with the economy is most likely to result in sudden currency declines that can exacerbate inflation, raise interest rates and reduce incomes further.