This article is an on-site version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning

Good morning and welcome to Europe Express.

The European Commission yesterday proposed new powers to step in and shore up strained supply chains in a crisis. We’ll explore how this fits in a broader policy shift towards an interventionist agenda in industrial policy, and who is driving it.

We’ll also bring you the latest from the European Central Bank which has put forward new guidance on how to make its balance sheet greener.

And in a letter seen by the Financial Times, employees at the Malta-based European Union Agency for Asylum have complained about alleged nepotism and mishandling of harassment claims by their chief, Nina Gregori, a Slovenian official who got the job in 2019 after a harassment scandal toppled her predecessor.

Ebbing free trade

Claims that the EU’s new supply chain crisis intervention powers represented a jump towards a “planned economy” were roundly dismissed by Thierry Breton, the internal market commissioner, when the legislation was unveiled yesterday, write Sam Fleming, Andy Bounds and Javier Espinoza in Brussels.

And arguably rightly so. The scope of the legislation is far more limited than that, granting the European Commission and member states the ability to jump in to redirect supply lines of key products only in dire emergencies and under very restricted circumstances.

But the mere existence of the proposed rules — which will need to be tussled over by member states — still tells us something important about the drift of EU policy. To some, it represents the latest step towards an increasingly interventionist model, frequently associated with capitals including Paris, which emphasises the role of the state in steering the fortunes of key industries.

Breton has been the commission’s most vocal champion of the goal of shoring up strategic sectors and enabling the EU to stand on its own two feet in the face of aggressive protectionist moves from other big powers — not least the US.

In pursuit of a strategic autonomy agenda, he has enthusiastically backed not only industrial alliances in important sectors, but also a big subsidy package aimed at doubling the EU’s market share of the global semiconductor sector and more recently a proposed law aimed at opening up more mines within the EU to unearth critical raw materials.

The scarring experience of the Covid-19 pandemic, when key supply chains froze and the US forced its industry to prioritise domestic pharmaceutical supplies, has played a big part in shaping the rules. So has the sense that the EU has been too squishy in the past when protecting its core interests in the international trade arena.

The single market emergency instrument that was launched yesterday had a difficult genesis within the commission, however. Earlier versions caused deep consternation among officials who prioritise free trade over the hefty hand of the state, and there was a fierce battle over the scope and potency of the new powers being created.

During the summer, a group of states including the Netherlands and Finland expressed their concerns to the commission, warning the proposal looked “less about facilitating a well functioning single market and more about steering industries in a non-crisis environment, to prepare for future unknown crises”.

Eastern European countries were also unhappy, said one person familiar with the debate: “It is the state directing companies what to do. It reeks of the communist era of five-year plans.”

Some of those concerns were assuaged in the final version of the rules, said diplomats. Pro-market officials sought to narrow the scope during the debate, tightening the circumstances when the EU could intervene to prevent supply chain crises and beefing up member states’ influence over the process.

The result, says one person familiar with the legislation, is that “both sides are happy” in the commission. “The proposal is seen internally as a well-balanced policy.”

Previously sceptical member states have also welcomed some of the last-minute changes in the proposed legislation. “It’s moved on quite a bit from earlier versions,” acknowledged one diplomat, while adding “There are still some quite far-reaching elements in there.”

Nevertheless, the deeper philosophical divisions over the nature and scope of the EU’s drive for “strategic autonomy” remain as acute as ever.

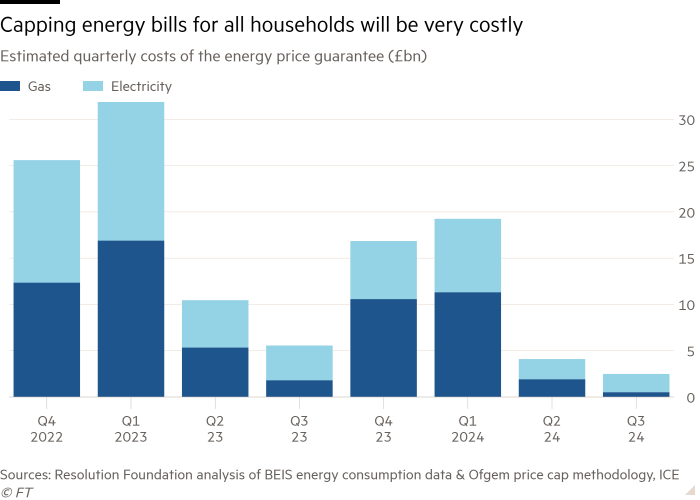

Chart du jour: Costly plan

Martin Wolf unpacks the British government’s plan to cap energy bills for households and concludes that it is ill-targeted, relies too much on public debt and misses the opportunity to impose a windfall tax the way other European countries are implementing.

Greener balance sheet

The European Central Bank published new guidelines yesterday for how it will “tilt” its corporate bond holdings toward greener companies, writes Leslie Hook in London.

The central bank is pushing ahead with its climate agenda even while it fights inflation, which rose to 9.1 per cent in the euro area in August.

Under the new rules for corporate bond purchases, the ECB will calculate a climate score for companies based on three factors: their past emissions, their future targets and the robustness of their emissions disclosure.

The policy shift will come into effect next month, and will only affect how the ECB reinvests the proceeds of maturing bonds it already owns.

Though the scores will not be made public, companies with a higher climate score will be more heavily weighted in the benchmark guiding the ECB’s purchases.

The move is a key step in the ECB’s plans to decarbonise its balance sheet, and will be followed by other changes, including new disclosure requirements for assets used as collateral.

The ECB has been at the forefront of efforts to limit climate risks in the financial system, and president Christine Lagarde has made fighting climate change a core goal of the bank.

In July an ECB stress test of 41 of the largest banks found that their potential losses from climate and energy transition risks came to around €70bn, though the ECB said this was an underestimate.

What to watch today

-

European leaders speak at the UN General Assembly in New York

-

EU affairs ministers meet in Brussels to discuss rule of law and Brexit

Notable, Quotable

-

Nuclear near miss: Russian forces carried out a missile strike that narrowly missed a nuclear power plant in southern Ukraine, according to Kyiv, days after an international watchdog warned that shelling at another atomic energy site risked causing a serious incident.

-

No more Mir: İşbank, one of Turkey’s largest banks has halted the use of the Russian Mir payment system after warnings from Washington about the risk of falling foul of US sanctions on Moscow.

Recommended newsletters for you

Britain after Brexit — Keep up to date with the latest developments as the UK economy adjusts to life outside the EU. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: [email protected]. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe