Competition for places at Britain’s top universities is growing fiercer, as falling per-student funding forces institutions to reduce their offers despite rising demand, according to higher education analysts.

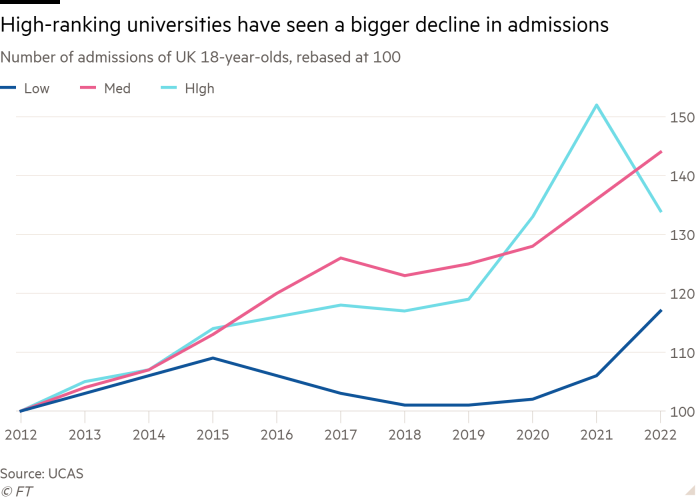

The number of 18-year-olds from England, Wales and Northern Ireland admitted to high-ranking institutions fell by 12.2 per cent this year, according to an analysis by higher education consultancy DataHE.

As freshers prepare to start term this week, analysts suggest that securing a place at the top tier institutions is getting tougher due to undergraduate funding falling in real-terms because of inflation, dissuading universities from expanding course numbers.

Mark Corver, director of DataHE and a former head of data at UCAS, the higher education body, said that rising demand for places had “collided with a reality of constrained supply at mostly higher tariff universities”.

The DataHE analysis, shared with the Financial Times, showed that two weeks after results day higher-tariff institutions had recruited 11,430 fewer 18-year-olds from England, Wales and Northern Ireland this year compared with 2021.

Total applications to this group — a rough indicator of appetite as students can apply to up to five choices — increased from 545,000 to 573,000.

The fall in admissions is partly because of the most competitive universities scaling back after a sharp increase in intake last year, when exams were cancelled because of the pandemic, resulting in record grade inflation and more students meeting their entry offers.

Before that, the number attending university had rapidly expanded for a decade. On results day last month, UCAS said that 425,830 students were accepted into university or college, the second highest on record and an increase of 16,870 compared to 2019.

However Corver said the fall in top tier admissions between 2021 and 2022 showed that universities were not expanding to meet demand because of financial pressures.

In August, inflation dipped to 9.9 per cent, and is expected to rise into the low double digits this autumn. However, tuition fees have only risen by £250 since being capped at £9,000 a year since 2012.

“They’ve got to balance the books,” he said. “That’s led to tactical decisions on admissions to go for the higher fee students, and a crimping of supply for home places at the universities people most want to go to.”

The Russell Group, which represents higher-ranking institutions, said universities were spending £1,750 more on each home undergraduate per year than they made in tuition fees and grant funding, and predicted the deficit would increase to £4,000 by 2024-25.

Universities UK, which represents the sector, has denied that places are being restricted. It highlighted that enrolment numbers have been growing in the long term and only dropped back compared to last year.

But it admitted that “erosion of funding for teaching UK students [was] a real problem”. Steve West, the group’s chief executive, last week called for a new funding settlement for the sector that was being “squeezed hard”.

Tim Bradshaw, Russell Group CEO, said it was “absolutely not” the case that domestic students were being “squeezed out”, pointing to a 14 per cent increase in the number of 18-year-olds admitted to high-tariff universities since 2012.

But, he acknowledged, that if universities continued to incur a teaching budget deficit this would “inevitably” have an impact on intake, “quality and choice for students, [and put] pressure on class sizes”.

Vice-chancellors are looking to raise revenue in other areas such as industry partnerships, accommodation rent, and taking on more high fee-paying students.

Charlie Jeffery, vice-chancellor of the University of York, said it was “inevitable” that universities would in time look to diversify funding streams.

For years, institutions have been seeking to draw students from overseas to help plug funding shortfalls. The number of international recruits — who pay an average of £13,000 a year more than their domestic peers — rose by 2,440 this year at higher ranking institutions compared with 2021, though this could partly reflect the easing of pandemic travel restrictions.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, a think-tank, said that budget pressures would limit institutions’ appetite to expand and prompt them to seek income from non-home tuition fees.

But he added that some universities were seeking to address the shortfall by taking the opposite approach: increasing their total numbers while being “more efficient”. This would mean spending less per student, he warned, potentially leading to savings such as larger class sizes that could threaten the quality of education.

UCAS figures showed low-tariff universities actually increased their intake of home 18-year-olds by 8,060, or 10.3 per cent this year, while medium tariff universities recruited an additional 6.2 per cent.

This resulted in the total market share of high tariff universities falling, to 32.1 per cent from 36.8 per cent last year.

“That is the great experiment going on,” Corver said. “They will be teaching these cohorts at a significantly lower unit of real resource than before — whether that will show up in the quality of teaching is unknown.”

Data analysis and visual journalism by Federica Cocco