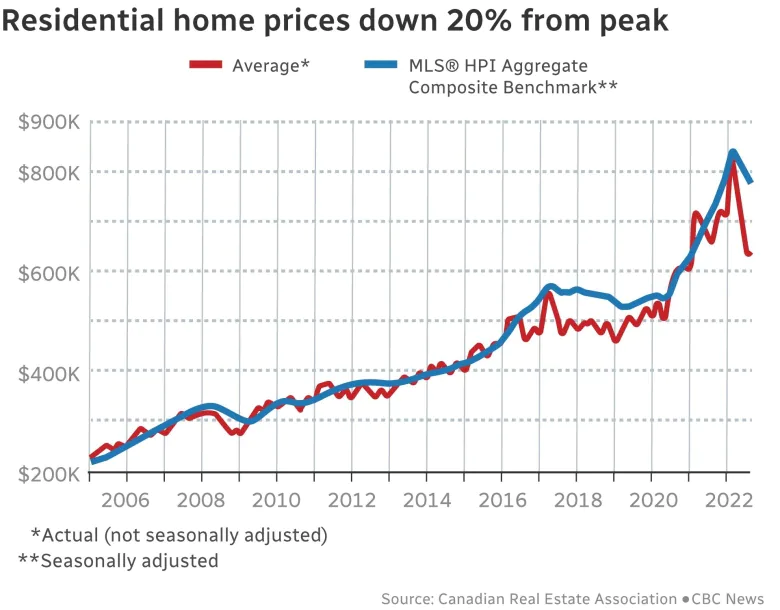

Canada’s real estate market has suddenly and dramatically cooled. Sales have dropped 24 per cent since this time last year. The average price of a home in this country has fallen by $179,047 since the peak in February.

And yet, has much actually changed?

“I consider it like letting the air out of a balloon,” said Colin Cieszynski, chief market strategist at SIA Wealth Management. “You don’t want it necessarily to pop and burst, but in the near term prices needed to come down to something that was a little bit more sustainable.”

For anyone trying to get into the market, the prospect of a cool down was always presented as an opportunity. But even with a 20 per cent drop in prices, Canada’s average home price has fallen back to where it was in early 2021.

What has changed, however, is how house-poor the typical Canadian family is feeling lately. Statistics Canada says the drop in home prices has helped drive the largest decline of household wealth this country has ever seen.

Billions lost in household net worth

It may be easy to look at the decline in home prices and, if you’re not an owner trying to sell, say, “That doesn’t affect me.”

But the reality is: Much of Canadian household wealth is tied up in home prices, the sector itself remains one of the biggest contributors to Canadian GDP, and it just took a hit.

Statscan says the net worth of Canadian households — defined as the value of all assets minus all liabilities — fell by a staggering $990.1 billion in April, May and June.

“This decline was compounded by a $389.8-billion drop in the value of non-financial assets, as the streak of gains in real estate that began in late 2018 was halted by a housing market grappling with rapidly rising interest rates,” wrote the data agency in a release last week.

The rest of the drop in household wealth comes as stock markets tanked in the second quarter. (Statscan’s figures only covered the period ending in June. Stock markets have recovered somewhat since then, but the once red-hot housing market losses have accelerated through July and August.)

As home values fall, there’s a knock-on effect for the rest of the economy, “like spending on building materials, spending on furniture, all that kind of stuff,” said BMO’s senior economist Robert Kavcic.

“We have more depressed housing activity that’s going to drag on real economic growth and is going to drag on job growth.”

As home values skyrocketed over the past decades, Canadian homeowners felt richer. They borrowed more and spent more, using their ever-rising home values as a sort of ATM.

As values fall off and interest rates rise, homeowners are less likely to borrow and spend.

Those interest rates will also slow the economy in another way, says Kavcic.

“If your mortgage payment is gone up $500 a month, or $1000 a month, that is immediately biting into discretionary spending that you could otherwise be spending elsewhere in the economy,” he told CBC News.

Inflation is not over

Meanwhile, inflation is eating into our purchasing power and eroding wage growth.

Combined, consumers are looking for ways to scale back spending, and small decisions make big differences when scaled out over a population.

“If you’re not going out for lunch, well, that’s one fewer sale at the local lunch place and maybe at some point, a couple fewer jobs,” said Kavcic.

He expects there are difficult days ahead.

Next week, Canada’s latest inflation numbers are set to be released. They’re forecast to show a deceleration in the main, headline number that in June reached a 39-year high of 8.1 per cent.

But economists are concerned that core inflation, which strips out volatile components like gasoline and food, is still rising. Cieszynski says the most recent inflation numbers from the U.S. show how tough it is to rein in rising prices.

“[Last week’s U.S.] numbers showed that inflation is sticky, it’s remaining high and it may or may not have peaked,” he said.

“Even if it does start to come down, it may come down much slower than [Wall Street] had anticipated.”

If inflation does persist even as higher interest rates bite into the economy, he says, central banks including the Bank of Canada would have to increase rates more than expected and remain high for longer than anticipated.

That would mean more turmoil for both stock markets and real estate markets. Which in turn would mean an even larger erosion of household wealth than we’ve already seen.