It was the scariest night of Andrew Grantt Conlyn’s life. He sat in the passenger seat of a two-door 1997 Ford Mustang, clutching his seatbelt, as his friend drove approximately 100 miles per hour down a palm tree-lined avenue in Fort Myers, Fla. His friend, inebriated and distraught, occasionally swerved onto the wrong side of the road to pass cars that were complying with the 35 mile- an-hour speed limit.

“Someone is going to die tonight,” Mr. Conlyn thought.

And then his friend hit a curb and lost control of the car. The Mustang began spinning wildly, hitting a light pole and three palm trees before coming to a stop, the passenger’s side against a tree.

At some point, Mr. Conlyn blacked out. When he came to, his friend was gone, the car was on fire and his seatbelt buckle was jammed. Luckily, a good Samaritan intervened, prying open the driver’s side door and pulling Mr. Conlyn out of the burning vehicle.

Mr. Conlyn didn’t learn his savior’s name that Wednesday night in March 2017, nor did the police, who came to the scene and found the body of his friend, Colton Hassut, in the bushes near the crash; he’d been ejected from the car and had died. In the years that followed, the inability to track down that good Samaritan derailed Mr. Conlyn’s life. If Clearview AI, which is based in New York, hadn’t granted his lawyer special access to a facial recognition database of 20 billion faces, Mr. Conlyn might have spent up to 15 years in prison because the police believed he had been the one driving the car.

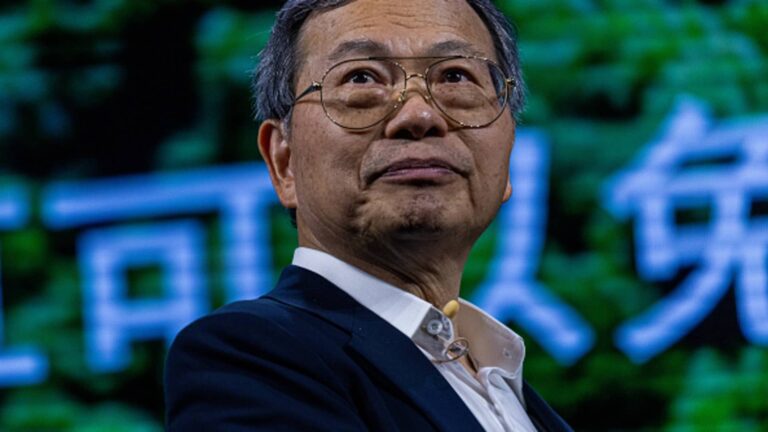

For the last few years, Clearview AI’s tool has been largely restricted to law enforcement, but the company now plans to offer access to public defenders. Hoan Ton-That, the chief executive, said this would help “balance the scales of justice,” but critics of the company are skeptical given the legal and ethical concerns that swirl around Clearview AI’s groundbreaking technology. The company scraped billions of faces from social media sites, such as Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram, and other parts of the web in order to build an app that seeks to unearth every public photo of a person that exists online.

“I think it’s a rare situation in which most defense attorneys would want to use it,” said Jerome Greco, who oversees a forensics technology lab at the Legal Aid Society, in New York City. “This is mostly being done as a P.R. stunt to try to push back against the negative publicity that Clearview has about its tool and how it’s being used by law enforcement.”

Civil liberty advocates believe Clearview’s expansive database of photos violates privacy, because the images, though public on the web, were collected without people’s consent. The tool can unearth photos that people did not post themselves and may not even realize are online. Critics say it puts millions of law-abiding people in a perpetual lineup for law enforcement, which is particularly concerning given broader concerns about the accuracy of automated facial recognition.

Clearview AI has been the target of multiple lawsuits, and its database has been declared illegal in Canada, Australia, Britain, France, Italy and Greece. It faces multiple multimillion-dollar fines in Europe.

The controversy around Clearview AI aside, some public defenders see potential benefits in having access to the company’s technology — and, in the case of Mr. Conlyn, it played an indispensable role.

“There is nothing worse than being held responsible for a crime you did not commit,” said Mr. Ton-That of Clearview. “I was honored to assist.”

The Samaritan Search

In November 2019, almost three years after the car accident, Mr. Conlyn was charged with vehicular homicide. Prosecutors said that Mr. Conlyn had been the one recklessly driving Mr. Hassut’s Mustang that night and that he was responsible for his friend’s death.

Read More on Artificial Intelligence

Mr. Conlyn vehemently denied this, but his version of events was hard to corroborate without the man who had pulled him from the passenger seat of the burning car. The police had talked to the good Samaritan that night, and recorded the conversation on their body cameras.

“The driver got ejected out of one of the windows. He’s in the bushes,” said the man, who had tattoos on his left arm and wore an orange tank top with “Event Security” emblazoned on it. “I just pulled out the passenger. He’s over there. His name is Andrew.”

The police did not ask for the man’s name or contact information. The good Samaritan and his girlfriend, who was with him that night, drove off in a black pickup truck.

The body-camera footage did not seem to hold much weight with the prosecution.

“There was contradicting evidence,” said Samantha Syoen, the communications director for the state attorney’s office.

Witnesses who had arrived late to the scene saw Mr. Conlyn pulled out of the driver’s side of the car. Mr. Conlyn said, and police body camera footage appeared to confirm, that the passenger’s side door had been against a tree, which was why he’d had to be rescued from the other side. The police found his blood on the passenger’s side of the car but also on the driver’s side airbag.

An accident reconstruction expert hired by the prosecution said the injuries to the right side of Mr. Conlyn’s body could have come from the center console, not the passenger door. After Mr. Hassut’s father sued Mr. Conlyn in civil court in 2019, for the wrongful death of his son, Mr. Conlyn’s insurance agency settled the suit, unable to prove that Mr. Conlyn had not been driving the car.

Mr. Conlyn, who is now 32, was a carpenter without much income. His lawyers, whose fees were paid by his family, filed an application with the court to declare him indigent so that any other expenses he incurred to defend himself would be covered by the state. The experts his lawyers hired struggled to gather evidence. It had been years since the accident; the Mustang had been flattened into a pancake and left out in the elements. His legal team became obsessed with finding the man in the orange tank top.

They asked for help from the public, providing an image of the man from the body camera to local news outlets and putting it on social media. They made fliers. One of Mr. Conlyn’s lawyers, Patrick Bailey, looked at the websites of local tattoo parlors. He searched nearby streets for a black pickup truck like the one at the scene that night and got access to county vehicle ownership records for black Ford Rangers, the model of truck he thought the man had been driving. He searched the names of over 1,000 Ranger owners on social media to see if any of them looked like the good Samaritan or his girlfriend. He did not know that the truck in question was actually a Nissan Frontier.

“We spent hundreds of hours looking for him,” Mr. Bailey said.

Mr. Bailey heard about facial recognition technology in late 2021 and began to research options for using it in Mr. Conlyn’s case. He tried a free facial recognition site called PimEyes, but the dark screenshot from the body camera footage didn’t get any good hits. In June, Mr. Bailey wrote an imploring letter to Hoan Ton-That, the chief executive of Clearview AI. He knew that the company was popular with local police and federal agencies, and that it claimed to have superior technology.

“I am aware that your company only provides facial recognition software to law enforcement agencies,” Mr. Bailey wrote. “What happens if those same agencies refuse to use Clearview AI’s important and powerful software to identify an otherwise unidentified eyewitness that could clear an innocent person?”

According to internal Clearview documents obtained by Buzzfeed, the Fort Myers Police Department had trial access to Clearview’s technology at some point before February 2020, running more than a dozen searches, but the department had not signed up for a paid account. A spokeswoman for the department declined to comment on the case.

Creative Thinking

Mr. Ton-That was accustomed to people asking to use his company’s tool.

“We have had a decent number of random requests,” Mr. Ton-That said. “Just random people saying, ‘Can you help find my long-lost daughter?’”

Typically, Clearview tells those people to contact local law enforcement. But Mr. Ton-That decided to grant Mr. Bailey’s request, and asked that he talk to the news media about it if the search worked.

This required some creative thinking. Clearview had recently settled a class-action lawsuit over privacy violations in Illinois by agreeing not to provide its tool to private individuals and companies, with the exception of financial institutions. Mr. Bailey was a private lawyer, but, because of Mr. Conlyn’s indigent status, he was also a subcontractor to the Justice Administrative Commission, a Florida state agency. In consultation with Clearview’s lawyers, Mr. Ton-That decided that this meant Clearview could allow Mr. Bailey to use the tool without violating the legal agreement.

“Within two seconds, I found a picture of him at some club in Tampa,” Mr. Bailey said.

The Clearview match looked identical to the man on the body camera, down to tattoos on his left arm. The website on which the photo appeared didn’t give the man’s name, but it did include the name of a man who had been with him at the club that night. Mr. Bailey contacted that person via Facebook and soon had the name of the man who had rescued Mr. Conlyn from the burning car five years earlier: Vince Ramirez, a construction worker who had lived in Fort Myers for only a few months before relocating to St. Augustine, in northern Florida.

When Mr. Bailey reached Mr. Ramirez by phone, he remembered the night vividly. He and his girlfriend were driving home when a car sped past them. A few minutes later, they came upon the same car on fire. Mr. Ramirez pulled over and got out.

“I was afraid the car was going to blow up,” Mr. Ramirez, 31, said in a phone interview. “I pulled open the door, jumped in and pulled him out of the passenger’s seat. It was a real adrenaline rush.”

When the police arrived, Mr. Ramirez answered their questions. But no one told him to stay, so he and his girlfriend went home. For years afterward, he told the story to family and friends, but he never realized that people were trying to find him until he heard from Mr. Bailey.

“The way I was found, it kind of shocked me,” Mr. Ramirez said. He had heard of facial recognition technology but had thought it was used only to find criminals.

“I’m grateful they did find me,” he added. “I didn’t want some innocent person to be sent to prison for 15 years for something he didn’t do.”

The prosecutor in the case deposed Mr. Ramirez on a Thursday afternoon in July, and dropped the vehicular homicide case against Mr. Conlyn that evening.

“That just goes to show you how important he was in this case,” Mr. Bailey said.

Facial recognition software like Clearview’s should “be available to the defense bar without, you know, too many hoops to jump through,” Mr. Bailey added. “Why is it so difficult for us to use this to exonerate somebody?”

New Customers?

The case inspired Mr. Ton-That to start offering Clearview’s tool to public defenders and lawyers contracted by the government to represent indigent clients.

“It would be free slash very inexpensive,” Mr. Ton-That said.

The company now offers them 30-day free trials, as it does its law-enforcement customers. It has charged police departments as little as $2,000 for a year’s access to its service, though Clearview says it has raised its prices.

“This really levels the playing field,” Mr. Ton-That said. “People would think of the technology a lot differently if public defenders had access to it as well.”

He said that access would “build more trust in the system.”

But public defenders, and experts in criminal defense, are skeptical. It might help them in some cases but at what cost?

Jumana Musa is the director of the Fourth Amendment Center at the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, where she works to keep defense lawyers informed about the newest surveillance tools used by law enforcement.

“They can offer it to everybody,” Ms. Musa said. “It is not going to wipe away the ethical concerns about the way in which they went about building this tool. The second thing it’s not going to do is make us feel comfortable with the secrecy around how this tool works.”

The problem with facial recognition, beyond bias concerns around how accurate it is across race, age and gender, Ms. Musa said, is a lack of transparency from law enforcement about how often it is used. Because any match the technology returns is considered only a lead, and not probable cause for an arrest, the software’s use is often not disclosed to defendants or their counsel, said Ms. Musa, which makes it harder to defend against.

“You don’t address issues in a broken criminal legal system by layering technology on them,” Ms. Musa said.

Mr. Greco, with the Legal Aid Society, said his organization was unlikely to use Clearview. He believes the company is offering its facial recognition tool to defense lawyers “in order to gain some form of legitimacy in its use in the criminal legal system.”

“I’m hesitant to begrudge any defense attorney from doing what they think is best on an individual case for an individual client because I do believe that is our obligation,” Mr. Greco said. “At the same time, I don’t think I can endorse the use of Clearview.”

But Jonathan Lyon, who is the investigator resource coordinator at the National Association for Public Defense and who runs a website called Internet Sleuth, predicted “huge interest” in the technology. He said the facial recognition that Clearview offers would be a helpful tool, particularly for lawyers who were trying to track down people who had witnessed a fight or attended a party where criminal activity had occurred.

“From an investigator’s standpoint, any tool I can get my hands on, I want,” Mr. Lyon said. “Particularly if the other side has it. That, to me, is a win.”