Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The financial outlook for England’s higher education sector has deteriorated since the start of the year, requiring universities to take “bold and transformative” action to avoid falling into bankruptcy, according to the sector regulator.

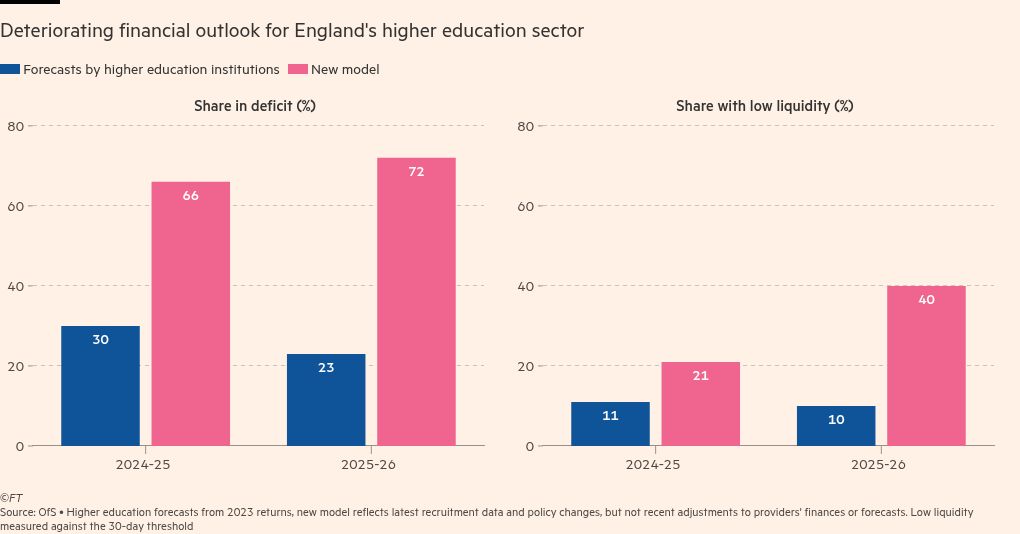

Almost three-quarters of such institutions are forecast to be in deficit in the academic year starting September 2025, following a £3.4bn decline in net income across the sector, according to a report published on Friday by the Office for Students.

The regulator blamed the squeeze on weaker than expected student recruitment, with admissions at some universities in line with the “more pessimistic” scenarios laid out in its last report into the sector’s finances published in May.

The report will increase fears of a looming financial crisis in the sector just weeks after the government announced it would increase the tuition fee cap next year for the first time since 2017 in an attempt to stabilise university finances.

Susan Lapworth, chief executive of the OfS, said a “challenging” recruitment market meant some universities would “lose out”, but that did not mean a significant number would close in the short term.

“Many universities have already taken steps to secure their long-term sustainability. For those that have not, the time to do so is now,” she said. “That is increasingly likely to involve bold and transformative action to reshape institutions for the future.”

The OfS said some providers would need to consider significant structural changes such as mergers, with the aggregate deficit expected to reach £1.6bn in 2025-26. The most recent financial returns for the HE sector from the end of 2023 forecast a surplus of £1.8bn.

Redundancy and restructuring programmes are under way at 76 higher education institutions.

About 100 providers fell short of their UK undergraduate recruitment forecasts for the current academic year, and roughly 150 failed to meet targets for international enrolments, according to OfS estimates.

The steep decline in international admissions particularly affected providers focusing on postgraduate-taught courses.

Home Office data published on Thursday showed there were 405,000 applications for UK study visas in the year ending October 2024, down from 499,000 the year before, representing a decline of 19 per cent.

Smaller and specialist education providers face more acute financial pressure than large universities, such as those in the Russell Group, where student recruitment has been closer to expectations, according to the report.

The analysis does not account for any financial adjustments made by universities since the start of this year, but does reflect recent policy announcements, including increased national insurance contributions for employers and higher tuition fee caps.

Sir Philip Augar, who chaired the 2018 Augar Review into the UK’s post-18 education landscape, said university leaders had “little option” but to bear down further on costs.

“They face difficult strategic choices and hard-headed realism needs to replace the sector’s recent bias to optimism,” he said. “Government also has a role to play and ending the tuition fee freeze can only be considered a first step.”

In July, the OfS advertised for a professional services firm to help with restructuring and to manage “potential market exits”. The regulator has outlined plans to improve monitoring by collecting more real-time financial information from providers.

Vivienne Stern, chief executive of Universities UK, the main sector lobby group, welcomed the increase in tuition fees but added the government needed to work with universities on a longer-term solution.

“Across the sector tough decisions have already been made to control costs, and universities will look to go further still to be as efficient and effective as possible,” she added.

The University and College Union, which represents lecturers, said the government needed to provide long-term public funding to universities.

“The tuition fee increase announced last week will not stop the rot; Labour now urgently needs to set out how it will put the sector on a sustainable footing by providing long-term public funding,” added UCU general secretary Jo Grady.

Education secretary Bridget Phillipson said the report showed exactly why the increase in tuition fees and the package of reforms announced last week were so essential.

“The dire situation we inherited has meant this government must take tough decisions to put universities on a firmer financial footing,” she said.

“I asked the Office for Students to refocus their efforts on monitoring financial sustainability in the summer. These findings show why that was needed, and why universities must do more to make their finances work.”