The fight over Canada’s controversial digital services tax may escalate this week as the deadline looms for the Biden administration to decide whether to proceed with dispute arbitration amid threats of retaliation from Donald Trump’s incoming administration.

On Aug. 30, United States Trade Representative (USTR) Katherine Tai filed an official complaint under the Canada–United States–Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) arguing that the three per cent tax Canada implemented over the summer unfairly discriminates against American corporations.

The move started a 75-day consultation period that ends this week. But with President Joe Biden’s administration now in a lame duck position, it’s not clear whether Tai will escalate the dispute by asking an arbitration panel to decide whether Canada’s tax actually violates CUSMA.

The USTR’s other option is to let this complaint slide for now, leaving it to the incoming Trump administration to pick up and pursue — which may carry even more risk for Canada.

“The first Trump administration … was very clear on digital services taxes. They believed that digital services taxes were a very clear indication that a country was specifically targeting the U.S. and targeting U.S. companies. It will be a ‘with us and against us’ scenario,” said John Dickerman, the Washington-based policy vice-president for the Business Council of Canada.

“I think there will be very little room for negotiation on DST.”

When Tai initiated the CUSMA dispute with Canada, the USTR’s statement also made it clear that it would continue to support U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s participation in talks among OECD and G20 countries to reach a multilateral agreement on taxing big global tech companies.

Those countries have been pursuing such an agreement in order to prevent digital companies from pitting competitive jurisdictions against each other and organizing themselves to minimize or avoid taxation.

Dickerman, however, said that under Trump, these discussions could be disregarded. “Multilateral solutions aren’t as appealing as bilateral solutions would be,” he said.

Business groups sounded earlier warning

Canada’s DST applies to firms that make more than $20 million in annual revenue from online marketplace services, advertising, social media and user data. It won’t apply to small start-ups. It’s triggered when the annual revenue of a tech giant crosses a set international threshold of more than 750 million euros ($1.1 billion Cdn).

The risk of direct tariff retaliation from the U.S. is one of the main reasons groups like the Canadian Chamber of Commerce have fought the implementation of Canada’s DST from the start.

Before the results of last week’s election were even known, Ontario Premier Doug Ford called for the tax to be paused, based on what he said he was hearing about how “furious” Americans were about it.

If Americans had elected more Democrats to Congress last week, it’s possible there would have been more patience, even support, for engaging in the multilateral process Yellen and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland were trying to steer toward a treaty.

Populist voices calling for some of these companies to be downsized or broken up — or to at least pay their fair share of taxes to fund social services — were getting some attention before the election. That may explain why the Biden administration wasn’t spending very much of its capital defending the trade interests of American big tech, much to the frustration of more hawkish voices in Congress.

The incoming Trump administration, however, is pretty tight with tech moguls like Elon Musk.

“A number of the key digital executives did reach out to Trump in the election,” Toronto and New York-based trade lawyer Mark Warner observed. He said he doesn’t think this bodes well for Canada’s tax after the inauguration.

“The digital stuff is easy for people to understand because it looks like, ‘Wait a sec, the only companies [Canada is] hitting are big American companies,'” Warner added.

“Whatever the logic of it is and how it is defined, it’s just easy to to frame an issue that way … ‘You say you’re our best friend. You’re going after our big companies. What is this?'”

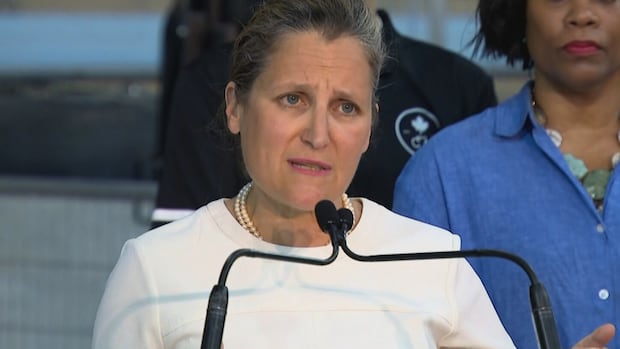

Despite earlier threats of retaliation from the U.S., Freeland’s office has taken note of how France, the United Kingdom and Italy collect digital services taxes.

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland is defending a controversial new tax on foreign tech giants like Netflix, Google and Amazon. She says it will bring in billions in revenue, but experts say consumers will end up paying more.

“Meanwhile, in Canada, some of the world’s largest firms are not paying their fair share, despite doing business and making huge profits in Canada. That isn’t right and puts Canada at a significant, comparative disadvantage,” Freeland’s spokesperson Katherine Cuplinskas told CBC News.

“Our preference has always been a multilateral solution,” she said, noting that Canada already has made “significant concessions” to try to land an international deal, including delaying the implementation of its own tax.

Speaking with reporters on Wednesday, Freeland said that France and Italy are “talking very seriously about significantly raising the level of their DSTs, and they are facing no trade consequences with the United States.”

“Canada should not be discriminated against,” she said. “Canadians need to have a level playing field on this issue.”

While the Trudeau government was hoping its DST would bring in over $7 billion during its first five years, it may have to concede this windfall to avoid punitive measures once Trump’s in charge.

That may disappoint progressives like the New Democrats who’ve argued for years that big corporations need to pay their share — but the fear of even greater economic harm may now need to focus minds in Ottawa.

Trump’s former national security adviser Robert C. O’Brien recently wrote that “allies who seek to constrain the U.S. economically must be reminded that our global technology leadership, including in the digital services market, is a national security issue for the U.S.”

Even if the Biden administration uses the weeks it has left to move this dispute to a CUSMA arbitration process, it’s not clear Canada will be able to defend its tax from claims that it shakes down American companies.

“Canada may have some safe harbour under their [CUSMA] cultural exception,” said Elizabeth Trujillo of the University of Houston’s law centre. She said that while she wonders whether the language Canada fought for in that deal — to protect its right to subsidize and support its own arts and media industries — could be applied in this case, it’s “arguable whether it’s truly a cultural exception.”

As the World Trade Organization also struggles to oversee the ever-expanding digital economy, Trujillo said it’s certain to be an issue when CUSMA comes up for its mandatory review, if not a full renegotiation, in 2026.

“It already is tense on these issues,” she said.