A new glowing nudibranch species is the first known to swim through the ocean’s midnight zone and has unique adaptations for life in this environment.

The newly discovered sea slug, Bathydevius caudactylus, or mystery mollusk, inhabits the deep-sea midnight zone, displaying unique adaptations like bioluminescence and a hood for capturing prey. It represents a significant find, potentially having a widespread habitat from the Pacific coast of North America to the Mariana Trench.

New Deep-Sea Species

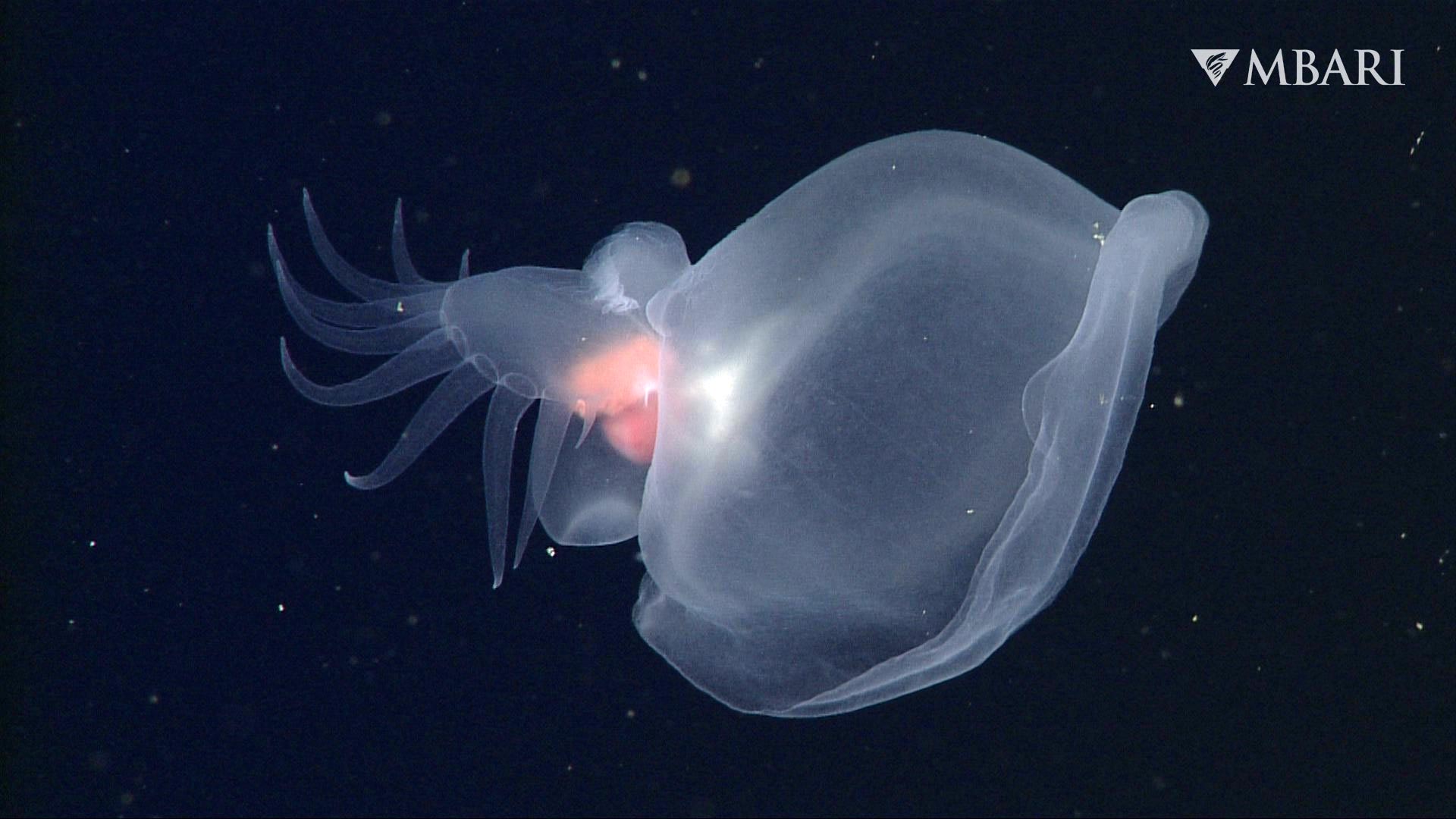

MBARI researchers have discovered a remarkable new species of deep-sea sea slug, named Bathydevius caudactylus. This creature, nicknamed the “mystery mollusk,” glides through the ocean’s midnight zone with a large gelatinous hood and a paddle-like tail, emitting brilliant bioluminescence. Today (November 12) the team published a detailed description of the mystery mollusk in the journal Deep-Sea Research Part I.

“Thanks to MBARI’s advanced underwater technology, we were able to prepare the most comprehensive description of a deep-sea animal ever made,” said MBARI Senior Scientist Bruce Robison, who led the study. “We’ve invested more than 20 years in understanding the natural history of this fascinating species of nudibranch. Our discovery is a new piece of the puzzle that can help better understand the largest habitat on Earth.”

MBARI scientists first encountered the mystery mollusk in February 2000, during a dive with the institute’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Tiburon near Monterey Bay, at a depth of 2,614 meters (8,576 feet). Since then, the team has used MBARI’s advanced underwater technology to gather extensive data on the species, ultimately reviewing more than 150 sightings of the mystery mollusk over two decades before publishing their findings.

The Unique Biology of the Mystery Mollusk

With a voluminous hooded structure at one end, a flat tail fringed with numerous finger-like projections at the other, and colorful internal organs in between, the team initially struggled to place this animal in a group. Because the animal also had a foot like a snail, they nicknamed this the “mystery mollusk.”

After gently collecting a specimen, MBARI researchers were able to take a closer look at the animal in the lab. Through detailed investigations of anatomy and genetics, they began to solve the mystery, finally confirming that this incredible animal is a nudibranch.

Most nudibranchs, also known as sea slugs, live on the seafloor. Nudibranchs are common in coastal environments—including tide pools, kelp forests, and coral reefs—and a small number of species are known to live on the abyssal seafloor. A few are pelagic and live in open waters near the surface.

Adaptations to Deep-Sea Life

The mystery mollusk is the first nudibranch known to live in the deep water column. This species lives in the ocean’s midnight zone, an expansive environment of open water 1,000 to 4,000 meters (3,300 to 13,100 feet) below the surface, also known as the bathypelagic zone.

The mystery mollusk is currently known to live in the waters offshore of the Pacific coast of North America, with sightings on MBARI expeditions as far north as Oregon and as far south as Southern California. An observation of a similar-looking animal by NOAA researchers in the Mariana Trench in the Western Pacific, suggests the mystery mollusk may have a more widespread distribution.

The mystery mollusk has evolved unique solutions to find food, safety, and companions to survive in the midnight zone.

Feeding Strategies and Survival Tactics

While most sea slugs use a raspy tongue to feed on prey attached to the seafloor, the mystery mollusk uses a cavernous hood to trap crustaceans like a Venus fly trap plant. A number of other unrelated deep-sea species use this feeding strategy, including some jellies, anemones, and tunicates.

Mystery mollusks are typically seen in open water far below the surface and far above the seafloor. They move through these waters by flexing their body up and down to swim or simply drifting motionless with the currents. To avoid being eaten, the mystery mollusk hides in plain sight with a transparent body. Rapidly closing the oral hood facilitates a quick escape, similar to the pulse of a jelly’s bell.

Defense Mechanisms and Bioluminescence

If threatened, the mystery mollusk can light up with bioluminescence to deter and distract hungry predators. On one occasion, researchers observed the animal illuminate and then detach a steadily glowing finger-like projection from the tail, likely serving as a decoy to distract a potential predator. “When we first filmed it glowing with the ROV, everyone in the control room let out a loud ‘Oooooh!’ at the same time. We were all enchanted by the sight,” said MBARI Senior Scientist Steven Haddock. “Only recently have cameras become capable of filming bioluminescence in high-resolution and in full color. MBARI is one of the only places in the world where we have taken this new technology into the deep ocean, allowing us to study the luminous behavior of deep-sea animals in their natural habitat.”

Reproduction and Genetic Uniqueness

Like other nudibranchs, the mystery mollusk is a hermaphrodite, possessing both male and female sex organs. The mystery mollusk appears to descend to the seafloor to spawn. MBARI researchers observed some animals using their muscular foot to attach to the muddy seafloor in order to release their eggs.

Detailed examination of specific gene sequences confirmed that the mystery mollusk is unique enough from other known nudibranchs to merit the creation of a new family, Bathydeviidae. Two shallow-water nudibranchs—the lion’s mane nudibranch (Melibe leonina) and the veiled nudibranch (Tethys fimbria)—use a hood to capture prey; however, this appears to be convergent evolution of a similar feeding method, as the mystery mollusk is only distantly related to these species. In fact, genetics suggests the mystery mollusk may have split off first on its own branch of the nudibranch family tree.

Conclusion and Future Implications

“What is exciting to me about the mystery mollusk is that it exemplifies how much we are learning as we spend more time in the deep sea, particularly below 2,000 meters. For there to be a relatively large, unique, and glowing animal that is in a previously unknown family really underscores the importance of using new technology to catalog this vast environment. The more we learn about deep-sea communities, the better we will be at ocean decision-making and stewardship,” said Haddock.

The mystery mollusk is just one of many fascinating discoveries MBARI has made in the midnight zone. To date, MBARI technology has been used to document more than 250 deep-sea species previously unknown to science.

“Deep-sea animals capture the imagination. These are our neighbors that share our blue planet. Each new discovery is an opportunity to raise awareness about the deep sea and inspire the public to protect the amazing animals and environments found deep beneath the surface,” said Robison.

Mystery mollusc (Bathydevius caudactylus) fact sheet

Common name: Mystery mollusc

Scientific name: Bathydevius caudactylus

Pronunciation: bath-ee-dee-vee-us caw-dack-till-usHabitat: midwater, in the bathypelagic zone

Depth range: 1,013 to 4,009 meters (3,323 to 13,153 feet)

Geographic range: currently known from the Northeastern Pacific Ocean, from Oregon to Southern California, but likely more widespreadSize: 14.5 centimeters (5.6 inches) (total length)

Diet: crustaceans, including mysid shrimpSwimming: Bathydevius caudactylus swims with up-and-down undulations of the entire body, from the hood to the tail. Quickly closing the hood propels the animal backward. Most individuals have been observed in the water column at depths of 1,013 to 3,272 meters (3,323 to 10,735 feet), either swimming slowly or passively drifting. Bathydevius caudactylus is neutrally buoyant and does not sink or rise in the water column when at rest.

Feeding: Bathydevius caudactylus uses a gelatinous hood to trap crustaceans. The bowl-shaped hood is highly elastic and may be up to 9 centimeters (3.5 inches) across. Meals are ingested through a funnel-shaped mouth at the back of the hood. Bathydevius caudactylus lacks the raspy tongue-like radula typical of bottom-dwelling nudibranchs and snails. Bathydevius caudactylus feeds on prey rich in nutrients, slowly metabolizing meals that may be few and far between in an environment where food is scarce.

Physiology: Researchers measured oxygen consumption of Bathydevius caudactylus with the Midwater Respirometer System developed by MBARI scientists and engineers. Bathydevius caudactylus has a metabolism much lower than that reported in other nudibranchs; in fact, respiration rates are more similar to those MBARI researchers have recorded in deep-sea jellies. The reduced respiration reflects the slower pace of life in the deep water column.

Bioluminescence: Researchers filmed bioluminescence from Bathydevius caudactylus in the field and the laboratory. Luminous granules in the animal’s tissues create a “starry” appearance across the animal’s back, including a diffuse glow in the oral hood and throughout the tips of the finger-like dactyls in the tail. Bathydevius caudactylus appears to drop luminescent dactyls as a decoy to distract predators, much like a lizard dropping its tail. The dactyls regenerate, with some Bathydevius caudactylus observed bearing dactyls of different lengths. Bioluminescence is uncommon among nudibranchs and snails, and Bathydevius caudactylus represents an independent evolution of this trait—just the third time bioluminescence has evolved in nudibranchs and the seventh time among gastropods.

Reproduction: Bathydevius caudactylus is a hermaphrodite with both male and female reproductive organs. Spawning individuals were observed on the seafloor at depths of 2,269 to 4,009 meters (7,444 to 13,153 feet). Bathydevius caudactylus is a solitary species, however, spawning individuals were occasionally seen in proximity to each other on the seafloor. One specimen collected by MBARI researchers released a ribbon of eggs in the laboratory. Eggs hatched three days later, developing into trochophore larvae with a round body and long hair-like cilia.

Etymology: The genus name Bathydevius reflects the “devious” nature of this deep-sea animal that fooled researchers with features unlike those of other known nudibranchs. The species name caudactylus refers to distinctive finger-like projections, or dactyls, on the animal’s tail.

Reference: “Discovery and description of a remarkable bathypelagic nudibranch, Bathydevius caudactylus, gen. et. sp. nov.” by Bruce H. Robison and Steven H.D. Haddock, 23 October 2024, Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers.

DOI: 10.1016/j.dsr.2024.104414

This work was funded as part of the David and Lucile Packard Foundation’s longtime support of MBARI’s work to advance marine science and technology to understand a changing ocean.