Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Global inflation myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Higher prices for staples such as vegetable oils, wheat, cheese and sugar have pushed food commodity costs to their highest level in 18 months, signalling more pain ahead for grocery shoppers and central banks.

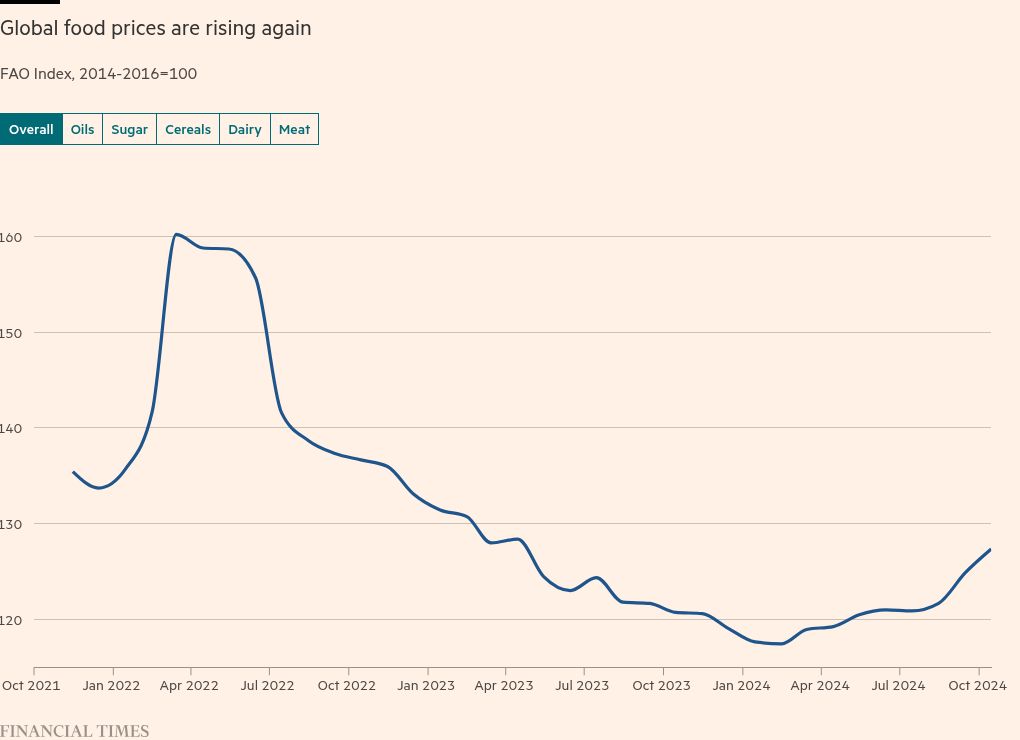

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s food price index rose to 127.4 in October — the highest level since April 2023. The figure, published on Friday, was up 5.5 per cent from October last year.

Prices for food commodities have risen steadily since the start of the year.

Although food costs remain well below levels reached in March 2022, consumers are already having to pay more for groceries as increases are passed on from food manufacturers to shoppers.

Food price pressures across the G7 major advanced economies ticked up for the first time in two years in September, complicating rate-setters’ attempts to cut rates to support growth and jobs.

Tomasz Wieladek, chief European economist at T Rowe Price, said the movements in commodity costs would stoke “food price inflation, which is a significant challenge for central banks”.

All of the G7 central banks, bar Japan, have cut rates this year on the back of signs that the worst bout of inflation in a generation is finally under control.

But Wieladek noted that the impact of the rise in food prices on households’ perceptions of inflation would be exacerbated by wholesale costs being priced in dollars, a currency that has strengthened following Donald Trump’s decisive win in this week’s US presidential election.

FAO economist Monika Tothova said that the figures suggested “a tighter market situation” for many commodities.

“While not reaching the levels of previous peaks, any shock — be it weather-related, a change in trade policy, or other factors — could exacerbate the situation in already tight markets,” Tothova said. “This could have significant implications for price levels and availability, affecting food import bills and food security.”

The UN recorded increases among most food categories, including a 7.3 per cent month-on-month increase for vegetable oils, a 2.6 per cent rise for sugar, and a 1.9 per cent increase for dairy products. Many of the rises were related to weather events, which reduced output.

Consumer price inflation has fallen sharply across most countries since reaching multi-decade highs in 2022, but higher food prices are complicating progress towards central banks’ 2 per cent targets.

In the US, annual food inflation in September rose to 2.3 per cent from 2.1 per cent in the previous month, the largest increase since August 2022.

Separate data by the Conference Board showed that US consumer inflation expectations for the year ahead rose to 5.3 per cent in October from 5.2 per cent last month, an uptick attributed to “continued upward pressures on food and services prices”.

In the UK, inflation of food and non-alcoholic beverages rose to 1.9 per cent from 1.3 per cent in September, marking the first increase since March 2023.

Flash estimates for October show that across the eurozone, prices of food, alcohol and tobacco rose at an annual rate of 2.9 per cent last month, up from 2.4 per cent in September. Unprocessed food inflation was up to 3 per cent in October, from 1.6 per cent in September and 1.1 per cent in the previous month.