When I arrive at Artist House Kadenówka, the gate stares me down with giant cast-iron eyes. Behind it looms a wooden house lifted straight from a fairytale. Both enchanting and creepy, it is neighboured incongruously by boxy midcentury apartment blocks in the Polish spa town of Rabka-Zdrój, an hour’s drive south of Kraków.

“I didn’t choose this house; it kind of came to me,” says artist Paulina Olowska of the building she bought in 2009. “Rabka has all these amazing abandoned buildings – and I found this one.” She swiftly inaugurated the house with a group project called the Mycorial Theatre. “The roof was completely open. The house was completely haunted. Lightbulbs were smashing. People were screaming. And I had,” she laughs mischievously, “lots of mushrooms.”

This rare example of traditional regional architecture has since become part heritage-preservation venture (Olowska worked with a local craftsman, Tadeusz Harkabuz, on the renovations, and the building has protected status), part artist residency and part project space. It’s a place that both provides inspiration for Olowska’s art and is an art installation itself. “Spending time at Kadenówka is like taking a clear walk in Paulina’s brain,” says Karine Haimo, vice president at Pace gallery in London, which co-represents the artist.

Born in Gdańsk, Olowska is best known for her figurative paintings that circle around themes of fashion and femininity, often nodding to the socialist history of eastern Europe. Yet the 48-year-old’s work spans film, photography, sculpture and performance. She has presented theatrical work at Tate Modern, published a magazine about art and theatre called Pavilionesque, and was the guest editor of the 2018 art issue of Polish Vogue. Her next solo exhibition, opening later this month at Pace Geneva, features a series of eerie paintings inspired by the dream-like photography of Deborah Turbeville. Olowska was drawn to the fashion editor-turned-photographer’s experimental images on a number of levels: “We share a certain melancholia for fashion, [a feeling] that fashion has a symbolic dimension connected to womanhood, and an understanding of how spirituality and symbols can be incorporated into different mediums.”

Olowska moved from Berlin to Rabka-Zdrój 16 years ago. Why? “Well, for love, of course,” she replies quickly, explaining that her husband’s parents lived in the town. “Escapism was also a part of it,” she says. “It was an artistic choice.”

A major inspiration was the long-sidelined Polish painter, illustrator and set designer Zofia Stryjeńska. “She started to work with design and tapestry, and was connecting to fairytales and folklore, and all in a cartoonish style that was closer to Walt Disney than any Polish paintings. She kind of directed me towards the countryside because she was always writing about how nature had a huge influence on her and her dreams and visions. I thought, ‘Maybe this is what I’m missing in this Berlin nightclub scene?’ You know, talking nonsense about the art world at 2am.”

She and her husband moved into a typical rural house, where she built an atelier in the garden. In the Polish countryside, she discovered a broader way of life centred around mythology, craft and magic. “I became a Slavic goddess,” she laughs, dressed today in a traditional folk‑style dress, the off-white fabric embroidered with red figures and floral motifs, inspired by traditional Polish paper cut-outs. Accompanied by her white-furred, baby-bear-sized Polish Tatra sheepdog, Bronka, she makes lunch of borscht, pierogi and assorted mushrooms – oyster, lion’s mane and shiitake, supplied by her “mushroom dealer” in Kraków. The set-up strikes a performative tone.

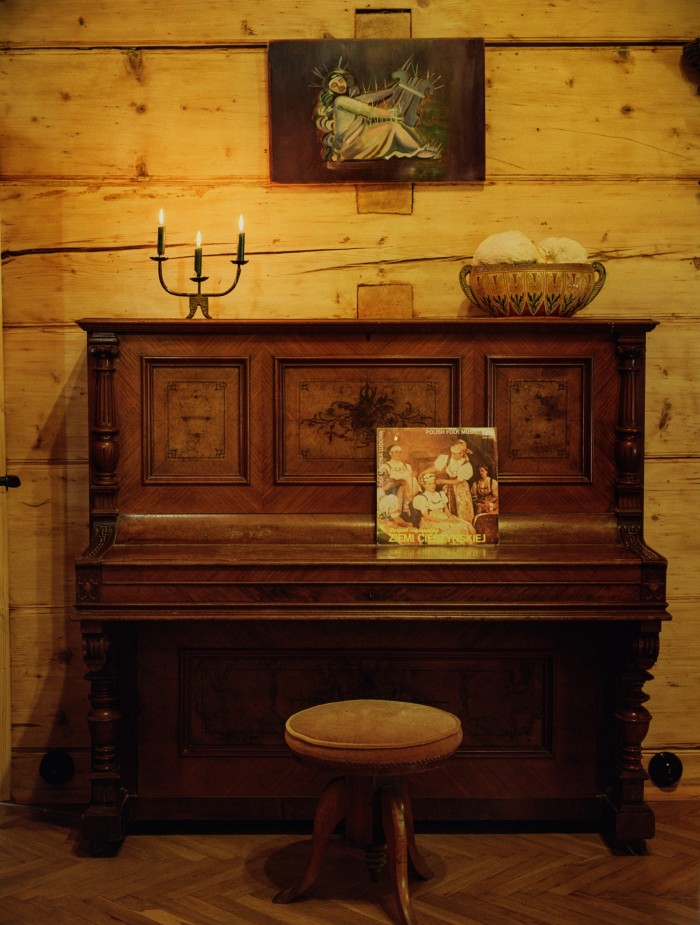

“It’s a theatre,” says Olowska, gesturing around the main central space of Kadenówka, overlooked on all sides by a first-floor balcony. “I think it was used for hosting soirées, masquerade balls and summer and New Year’s Eve parties.” The house was designed in 1932 by Adam Kaden, a writer, painter and designer whose father, a doctor, owned the town’s medical centre. “They were prosperous bourgeoisie, and Adam was the bon vivant of the family,” says Olowska. The house is an anomaly in its combination of architectural influences: modernist, Zakopane style (the arts and crafts-adjacent aesthetic movement pioneered by Stanisław Witkiewicz and named after a nearby town) and Hutsulian. “The Hutsulian take is from the Ukrainian highlanders,” says Olowska, highlighting its influence on details such as the carved wooden door handles and the small sun- and moon-shaped windows in the loft. “Folk is one of the themes of this house.”

Olowska is building on this theme with her own collections. Ceramics by Polish manufacturers Koło, Włoclawek and Łysa Góra line the walls of the kitchen; there are Zakopane style rugs on the floors; and patchworked bedspreads from the Cepelia, a state-run cooperative founded in 1949 that shut up shop four years ago. “In the 1960s everything was creative, even the garbage cans.” She shows me a concrete rubbish bin shaped like a bear outside the front door: “It’s from socialist times.”

Olowska’s vision isn’t only about nostalgia, though. She’s interested in how these creative and romantic notions can be relevant for a new generation. She does this by inviting international artists to Kadenówka, such as the American Marnie Weber and Devon‑based Alexis Soul-Gray, who stayed there for 10 days with her family. “I think Paulina looks for unusual talent to support,” says Soul-Gray. “She has a motherly intent to help other artists.”

She’s also a champion of Polish talent. The gate is a commission by contemporary Kraków-based artist Małgorzata Markiewicz, combining archaic and traditional symbols – “the Roma wheel, the house of magic and a Zakopane parzenica”. Around the house there are stained-glass windows and lights by young Kraków-based Marcin Janusz; a sculpture by Warsaw artist Agata Słowak; one of Romani artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s textile collages; and several dark and brooding paintings by surrealist artist Luka Woźniczko. “You are going to know the whole Polish art scene with all these names,” she says happily. “In the future, this will be a museum for contemporary art and folklore.” She has further plans to open a museum of puppetry in Rabka, in the old puppet theatre building she covered with murals 10 years ago. “But that’s another story…”

Rabka-Zdrój, with its hiking trails among the picturesque Gorce mountains, has long been a holiday spot. In the 1920s it bloomed as a spa destination, taking advantage of the mineral-rich waters of the Raba river, and was also used a place of rehabilitation for sick children. “It’s very interesting because it has these huge old sanatoriums,” says Olowska. “They’re empty, and they’re haunted.”

The town is the subject of a recent book, The Town of Children of the World by Polish writer Beata Chomątowska, who spent her summers in Rabka as a child. “The town has a very pastel, official, utopian image, but I sensed something underneath,” Chomątowska says. “It’s a very Freudian place, a mysterious place that has been somehow lost in time. My colleague described it as the Polish Twin Peaks. I discovered the shadow side of Rabka. I spoke to people who were ‘cured’ here as kids and their memories are full of horror.”

The darkness of Rabka is present in Olowska’s work too. It’s there in the winter landscapes and black-clad women of her new paintings, and in the life-size, puppet-like sculptures, shown at Pace London last year and now residents of Kadenówka, which are inspired in part by the Polish Marzanna dolls that symbolise Morana, the Slavic goddess of winter, plague and death. It’s a Slavic tradition to burn and then drown the straw-braided doll on the first day of spring to mark the end of winter – a ritual that Olowska carried out in 2021 when she co-curated the show Mora Zmora: Femme mythological figures in Slavic folklore at Organistówka (another of Rabka’s wooden buildings, now turned into holiday apartments, next to the towering 17th-century church of Saint Mary Magdalene that today houses a folk museum).

Her second artists’ gathering at Kadenówka was dedicated to mycology and magic, in a bid to “clean the house”, spiritually, through rituals and healings. “Dealing with witchcraft influenced my work a lot, but then – and I don’t know if it was connected or not – I actually had a real meltdown,” she recalls. “I started to question everything.” And she hid away her magic books.

Not that she’s stopped with magic entirely. When she texts me later, she signs off with the witch emoji. And when she curated the Pace booth at Art Basel Paris last month, she called it Mystic Sugar: a show of her work and others’ billed as “a contemporary reappraisal of the witch as a powerful symbol of liberation and otherworldly perception”.

“My priority with my work is to take things that are out of the mainstream and try to question them,” she concludes. “And now folk is in fashion. People are drawn to it because it’s unregulated, it’s not hierarchical – it’s wild.”

As to whether the house is still haunted – “What do you think?” Olowska shrugs. She then smiles her elfin smile. “Would you sleep here overnight?”

Paulina Olowska and Deborah Turbeville: Widows of the Wind is at Pace Geneva from 21 November to 7 February 2025