Rachelle and Kelly Swan live in a relatively cramped space now. But the upside to their rented low-income government house is that it’s away from the haunting site their family occupied for two years, filled with screeches, high-pitched chirps and squeaks from constantly flapping bats.

The couple bought their house in Spiritwood, about 170 kilometres northwest of Saskatoon, two years ago. They gave up their keys to the bank voluntarily in May, closing the door on the bat-infested house.

Rachelle said that as far as the bank is concerned, they just stopped making their mortgage payments. The move a couple of blocks down the street, she said, has left her with a credit that’s hit rock-bottom and a down payment she’s never going to get back.

“We basically lost everything,” Rachelle said.

“We can’t buy anything for up to seven years. We can’t trade our vehicles. We can’t even finance a new computer because we just have no credit whatsoever.”

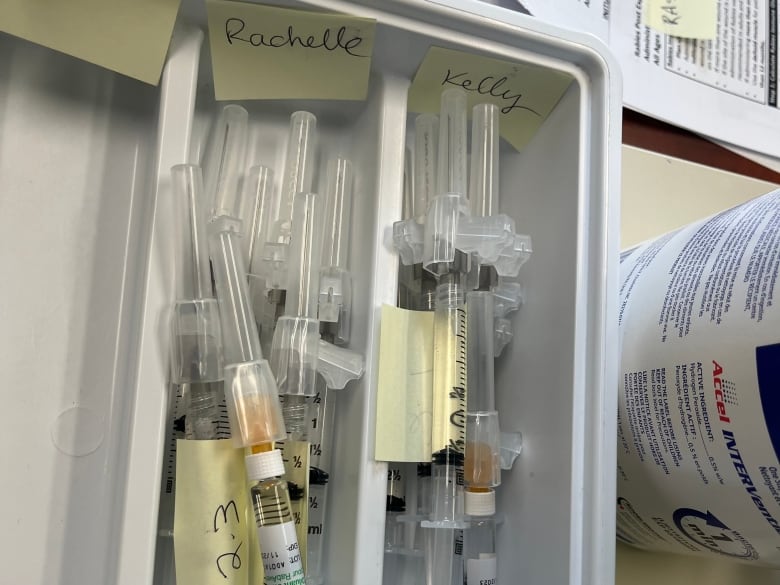

When Rachelle walks past the now-abandoned house, she said she can’t help but feel disappointed in how the authorities failed their family. The family of five was also considered a high risk for rabies and had to get a total of 47 rabies injections.

“It really makes me angry that was really what it came down to — that [leaving] was our only option.”

Rachelle and Kelly moved to the new place with their three kids and their oldest daughter’s boyfriend. Between the six of them, they had one bathroom to share, and it’s still cramped even after their daughter and her boyfriend left to go to university.

“It was tight and it was, I mean, super grateful we got the place because it’s a nice little house and it’s, you know, it’s safe and whatever, but it wasn’t ideal,” she said.

Rachelle and Kelly Swan bought their house in Spiritwood two years ago. They gave up their keys to the bank voluntarily and foreclosed on the bat-infested house in May.

Rachelle said she went back to the house a few months ago to get some leftover items and she saw one bat “hanging out” on the wall, and one near the vent where her kitchen table once was.

According to Saskatchewan’s Bat Exclusion Policy, bats can only be excluded with a permit, allowing exit but not re-entry, from buildings in May or September. It says considerations will be made by the Ministry of Environment on a case-by-case basis outside of May or September.

“Taking steps to prevent bats from coming into living spaces while undertaking exclusion work during the permitted times respects both human and animal needs,” the Ministry of Environment said in an emailed response.

The ministry said homeowners are responsible for all costs associated with exclusion efforts. There is no provincial program to assist property owners with bat exclusion or other wildlife-related remediation costs, it said.

For two years, Rachelle said, they tried exploring “every option” available to them before handing over their house. She said they contacted exterminators, conservation officers and roofing companies.

Rachelle said they spent more than $5,000 getting the roof sealed up with silicone and installing bat cones that have a one-way valve so that the animals can leave but not come back in.

Shortly after, they found one bat in their kitchen aquarium and six more in a mouse trap that they had set out, thinking they had seen mouse droppings.

She said the ministries of environment, health and housing, Premier Scott Moe — who is the area’s MLA — and MP Gary Vidal didn’t provide any plausible solutions either.

“I find it kind of upsetting in some ways, though, that the government wouldn’t help us at all with any of the issues in our old home, and now we’re still under the government thumb living in one of their rentals,” Rachelle said. “That’s a tough pill to swallow for me and my spouse.”

Moe didn’t respond to CBC’s request for a comment.

Killing the bats wasn’t an option.

In Saskatchewan, all bats and the places they inhabit are protected by The Wildlife Act. Two of the eight bat species found in Saskatchewan are also listed as endangered under the federal Species at Risk Act, with three additional species under consideration to be added to that list.

Rachelle said she feels the rules don’t do enough to consider cases like theirs.

“It’s just like they’re like, ‘Oh, we have to protect them, but once they’re in your home, we’re not going to do anything.'”

Perry Reavley, president of Critter Gitter Wildlife & Pest Control, said he’s seen bat exclusion attempts that aren’t at par with what he believes should be industry standards.

“The companies just aren’t doing the work properly. They don’t really know actually what they’re doing and causing more problems than they’re doing good,” Reavley said.

Reavley completed an exterior inspection of the Spiritwood home last fall. He said he would blame incompetence by previous contractors that led to the issue getting worse.

“It’s definitely lack of training, lack of education,” he said.

Reavley said bats have an extreme location loyalty and a sense that “it’s their house, not yours.” He said bats can reappear even a decade after they’ve been expelled from a house. The way that the legislation around expulsions works means people can fall through the cracks, Reavley said.

“Unfortunately, the Ministry of Environment doesn’t get involved with the actual exclusion process. They issue the policy and the permits to do so,” he said.

Halloween may be next week, but for one Spiritwood, Sask., couple, their house feels like Halloween year-round. A number of bats have made themselves at home in their roof and there’s almost nothing the couple can do about the problem.

Rachelle said they had to move out for the house, even if it made for a financial blow.

“Who wants to bring my nieces to my house for the weekend with that potential risk? Not to mention that it was creepy and scary for little kids. Like, they were really, really loud in my daughter’s walls,” she said.

What she would have done differently is not seek help at all, Rachelle says.

“I would caution anybody who goes through this — until the government can find some better way of dealing with this — I would just lie and kill them,” she said.