It’s usually frowned upon when politicians change economic targets to suit their agenda. But Britain’s chancellor, Rachel Reeves, appears to have pulled the wool over most people’s eyes.

Britain needed to raise public investment to improve its slow-growth malaise. But the fiscal rule inherited from the Conservatives — to ensure public sector net debt as a per cent of GDP is falling in five years’ time — afforded little ‘headroom’ to raise capital expenditure.

Reeves punted for a binding “golden rule”, to balance the day to day books, which, sensibly, created more room to borrow for long-term investments. But Labour’s manifesto still committed to having the debt ratio falling within five years.

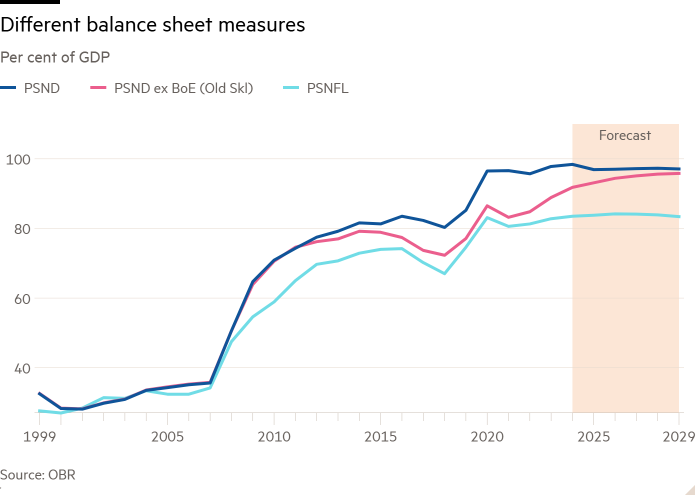

Her answer? Change the definition of debt. The era of public sector net debt (PSND) is over (for now) and public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL, often pronounced ‘persnuffle’) is in.

Reeves’ new “investment rule” is to ensure PSNFL is falling in 5 years (and, eventually, within 3).

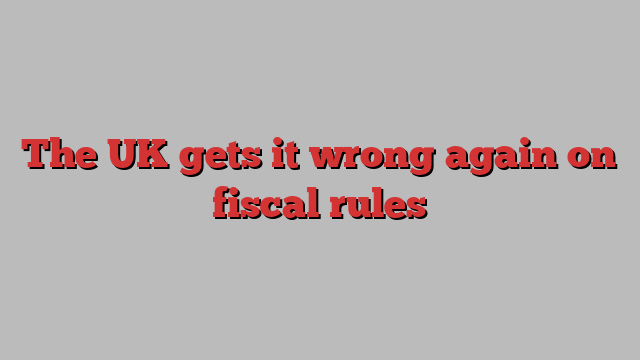

FTAV reckons it won’t be long before we start lamenting the change, and calling for another one. As is the norm in Britain: the average lifespan of a UK fiscal rule is 3.8 years — the shortest across the OECD — according to the Institute for Government:

Reeves got this through because:

— 1) Britain desperately needs to raise investment;

— 2) The gilts market didn’t crash à la Truss (a pretty low bar to clear);

— 3) There was so much else to digest in this Budget; and

— 4) Some well-known economists endorsed it.

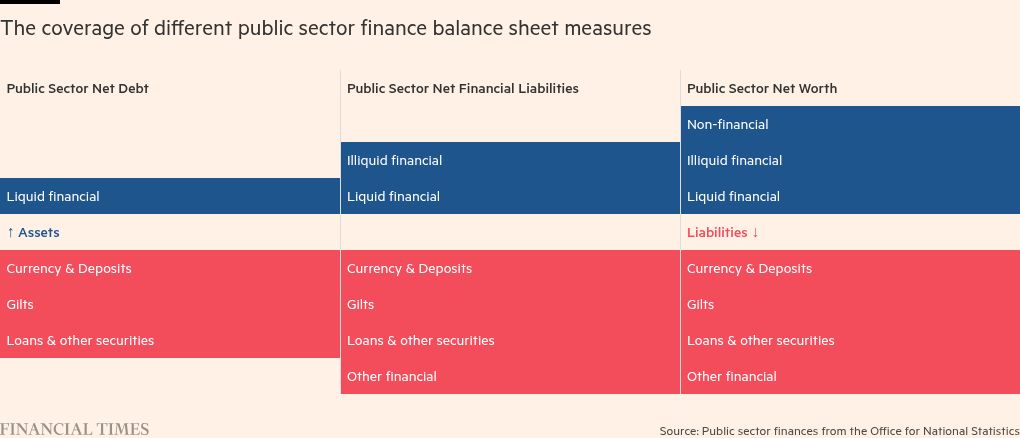

Shifting to PSNFL gave the Chancellor a larger headroom against her “investment rule” of around £49.1bn (she used just over £33bn of this).

Although gilt yields have climbed, bond markets were likely, initially, placated by Reeves’ decision not to eat into all the headroom, and her tougher, binding, “golden rule”.

None of that means it was the right choice. Here are the two key flaws:

1) What are we actually trying to measure?

The Chancellor’s speech claimed the change allows the UK to “count the benefits of investment, not just the costs”.

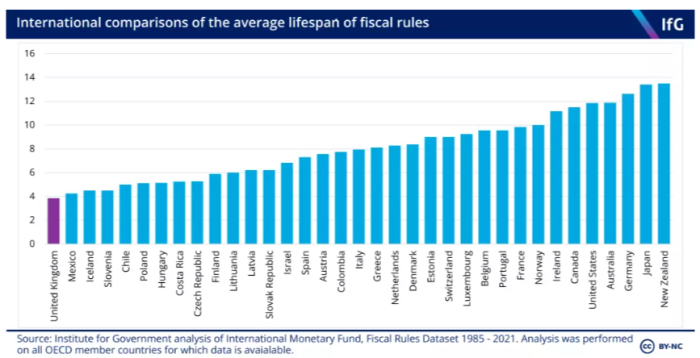

That is, indeed, a weakness of PSND. Investment creates assets, which adds economic value. But PSND is all about liabilities, net of liquid financial assets . . . for good reason. Creditors buying Britain’s debt use it as one gauge of the government’s ability to pay them back.

Assets like roads, pylons, and wind farms — the types of things Britain will actually need to invest in — are not even included in PSNFL. And second, they are valued at replacement cost. Creditors want to know if the asset generates a flow of income (tax or fee revenues), which the government can pay them back with. But physical assets cannot be liquidated in this way.

PSNFL excludes physical assets, but includes:

— liquid financial assets/liabilities

— illiquid financial assets/liabilities: loan assets (such as student loans and from the Help to Buy scheme), equity assets (mainly from public sector funded pension schemes and equity stakes), and securities from the BoE’s asset purchase facility/Term Funding Scheme

Again, it is not like student loans or equity holdings can be quickly sold off to pay back bondholders (albeit they can often be sold more easily than physical assets).

This strikes at the heart of the problem: a debt target is primarily a tool to track debt serviceability. There is, of course, a case for monitoring how public investments create assets and add to the country’s worth, but these two aims should not be conflated.

Admittedly, PSNFL would encourage a greater focus on assets. For instance, it removes the incentive to sell financial assets just to meet the debt target (as they appear in both assets and liabilities).

But it also introduces bad incentives, too:

— 1) A preference for financial assets relative to physical capital;

— 2) A motivation to convert funded pensions to unfunded pensions (whose liabilities are not included in PSNFL); and

— 3) A temptation to play with loans (a decision to write-off a loan could come long after the probability of repayment has fallen)

2) Mo’ assets and liabilities, mo’ measurement problems

Then there are the practical issues associated with adding more into the secondary fiscal target.

The first challenge is valuation. Market values are used where possible, or present values. For instance, as student loans are income contingent and may not be repaid, the Office for Budget Responsibility uses the present value of expected future repayments. That makes sense, and means most assets and liabilities will evolve as the economy does.

Loans, however, are recorded at a nominal value. The OBR, which has to make sense of all this stuff, gets around this by estimating the probability of write-offs to shrink the loan book.

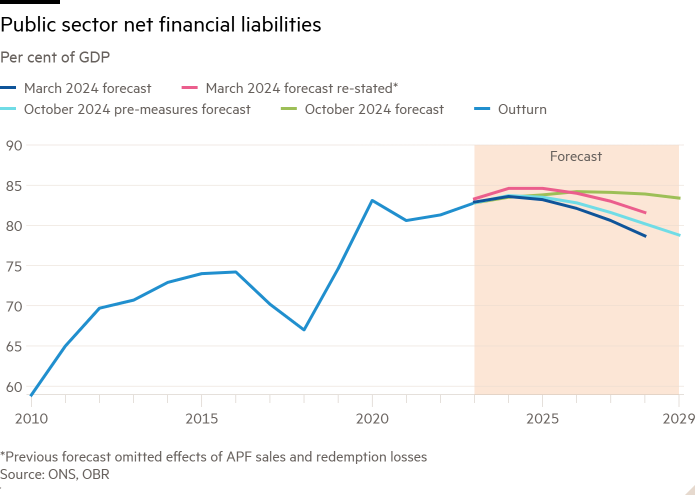

The challenges and assumptions involved in making such valuations can lead to huge swings in PSNFL. Ahead of this Budget the OBR had already erred in its March 2024 measurement of PSNFL, which ate into Reeves headroom by around £18bn this time around (see chart below — for context, Reeves has just £15.7bn of headroom). Get used to more of that.

Let’s look at some more tricky areas:

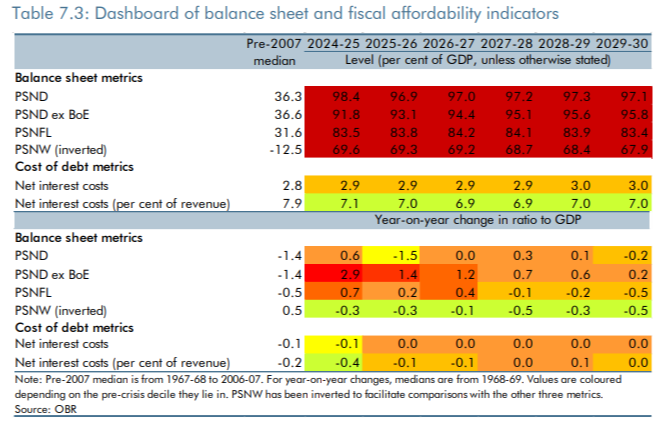

— 1) Equity holdings: These are assumed to rise in line with nominal GDP. But, as the OBR notes: “Were equity price growth to be 2 percentage points less than nominal GDP growth, PSNFL would be £10 billion higher.”

— 2) Funded pensions: These are revalued with long lags. A revaluation of the local government pension scheme in 2016/7 led to a £80bn increase in pension liabilities. The OBR adds: “The forecast model for these pensions is also currently not sufficiently rigorous”.

— 3) Loans: Changes in student loans policy can alter the value of the book. But more broadly differences in predicted write-offs versus actual write-offs will matter. (The OBR will assume a 12 per cent write-off rate for the National Wealth Fund).

If this all sounds complicated, that’s because it is.

There were plenty of calls before this Budget (including from FTAV) to remove the effects of the Bank of England’s asset purchase facility from PSND, partially as a result of the weird OBR guesswork underpinning how the measure is calculated.

A shift to PSNFL introduces far more assumptions: the OBR will now be involved in making a number of uncertain additional forecasts, which will influence fiscal policy.

In the ONS’s own words:

Relative to public sector net debt (PSND), estimates of PSNFL are usually subject to greater levels of revision extended over a longer period as source data in some cases come with longer lags. For example, the time-lag for public sector funded pensions liabilities data can be between three and five years, depending on when valuation assessments are made.

In summary, Reeves’ move to PSNFL only really makes sense in the context of adding to her headroom. It does not account for the type of investments Britain needs. It muddies the water for creditors in part because additional assets and liabilities involve numerous forecasts, and assumptions, which adds uncertainty and sensitivity to any measure of the headroom. It also creates plenty of room for fiddling.

Basically. Britain has arbitrarily shifted emphasis towards a new “investment rule” that is more opaque and harder to hold the government accountable against for both fiscal and economic goals.

You may think FTAV is just being a spoil sport. A number of economists have backed Reeves’ rules (even the IMF, and Mario Draghi). Indeed, every debt metric has its problems (public sector net worth is even more problematic, as valuing physical infrastructure is a nightmare). Fine. But she could have done better.

3) A better tomorrow

How? First, stick to traditional, well-understood debt metrics: debt-to-GDP ratio, interest payment, average maturities, etc. But, also, allow the OBR to make a holistic judgment about debt sustainability over a longer horizon (since supply-side policies take longer to deliver returns).

This broader debt sustainability judgment could consider a plethora of balance sheet metrics — assets, liabilities etc, as the OBR already does in its heat map. (There is a rationale to monitor whether investments are creating value)

The OBR might, for instance, say; although debt to GDP is rising in the fifth year, enough of the additional borrowing goes towards credible revenue-raising investments to bring debt sustainability back into line. It might also introduce probabilities to reflect various sensitivities, at different time horizons.

This would put greater emphasis on the OBR measuring the economic impact of government policies into the future better, which is where the Treasury warrants greater accountability. Instead, the shift to PSNFL will now focus OBR resources on trying to measure various assets that have little direct relevance to debt sustainability or growth, to keep the focus on the “headroom”.

A broader approach would limit exposure to various measurement sensitivities in single measures, better encapsulates the idea the debt sustainability is more complicated than a single metric too, and gives room to make good investments out of borrowing. Sadly, Reeves missed the opportunity to kick-start broader reform of the fiscal framework.

Don’t be surprised if in a few years time Britain again starts discussing how the rules need changing again. PSNFL won’t last long.

Further reading

— The OBR’s mean decision on quantitative tightening