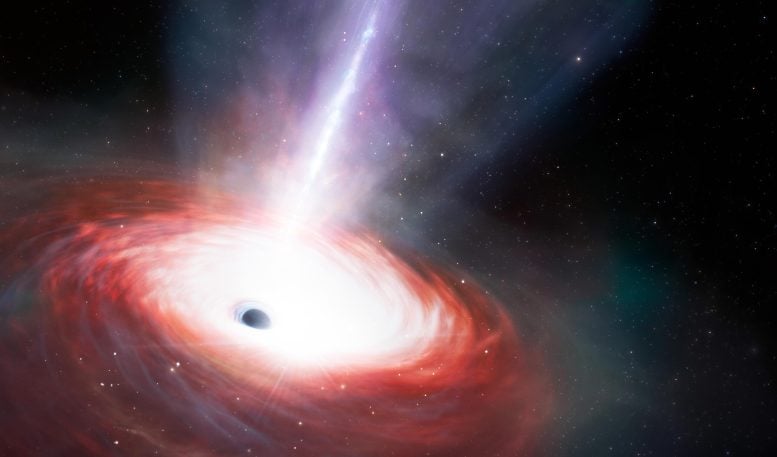

A low-mass supermassive black hole appears to be consuming matter at over 40 times the theoretical limit.

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope discovered LID-568, a supermassive black hole feeding at a rate 40 times its Eddington limit, seen just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang. This exceptional observation has provided new insights into black hole growth from initial ‘seeds’ and challenges current theories with its rapid accretion rate and powerful outflows.

Supermassive black holes are found at the center of most galaxies, and modern telescopes have begun observing them surprisingly early in the Universe’s history. Understanding how these black holes grew so large so quickly has been a major challenge. However, astronomers recently discovered a low-mass supermassive black hole rapidly consuming surrounding material just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, offering new clues about how black holes in the early Universe could have grown so fast.

Discovering LID-568

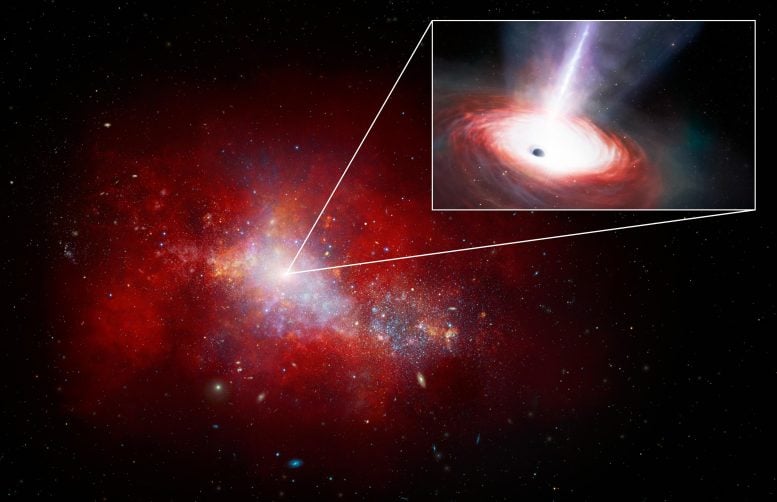

The black hole, named LID-568, was identified by an international team of astronomers led by Hyewon Suh of the International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab. Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the team studied a group of galaxies selected from the Chandra X-ray Observatory’s COSMOS legacy survey. Although these galaxies are extremely bright in X-rays, they remain invisible in optical and near-infrared light. Thanks to JWST’s exceptional infrared sensitivity, astronomers could detect faint emissions from these galaxies, including the newly discovered LID-568.

LID-568 stood out within the sample for its intense X-ray emission, but its exact position could not be determined from the X-ray observations alone, raising concerns about properly centering the target in JWST’s field of view. So, rather than using traditional slit spectroscopy, JWST’s instrumentation support scientists suggested that Suh’s team use the integral field spectrograph on JWST’s NIRSpec. This instrument can get a spectrum for each pixel in the instrument’s field of view rather than being limited to a narrow slice.

Breakthrough in Black Hole Research

“Owing to its faint nature, the detection of LID-568 would be impossible without JWST. Using the integral field spectrograph was innovative and necessary for getting our observation,” says Emanuele Farina, International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab astronomer and co-author of the paper appearing today (November 4) in Nature Astronomy.

JWST’s NIRSpec allowed the team to get a full view of their target and its surrounding region, leading to the unexpected discovery of powerful outflows of gas around the central black hole. The speed and size of these outflows led the team to infer that a substantial fraction of the mass growth of LID-568 may have occurred in a single episode of rapid accretion. “This serendipitous result added a new dimension to our understanding of the system and opened up exciting avenues for investigation,” says Suh.

Feeding Beyond the Limits

In a stunning discovery, Suh and her team found that LID-568 appears to be feeding on matter at a rate 40 times its Eddington limit. This limit relates to the maximum luminosity that a black hole can achieve, as well as how fast it can absorb matter, such that its inward gravitational force and outward pressure generated from the heat of the compressed, infalling matter remain in balance. When LID-568’s luminosity was calculated to be so much higher than theoretically possible, the team knew they had something remarkable in their data.

“This black hole is having a feast,” says International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab astronomer and co-author Julia Scharwächter. “This extreme case shows that a fast-feeding mechanism above the Eddington limit is one of the possible explanations for why we see these very heavy black holes so early in the Universe.”

These results provide new insights into the formation of supermassive black holes from smaller black hole ‘seeds’, which current theories suggest arise either from the death of the Universe’s first stars (light seeds) or the direct collapse of gas clouds (heavy seeds). Until now, these theories lacked observational confirmation. “The discovery of a super-Eddington accreting black hole suggests that a significant portion of mass growth can occur during a single episode of rapid feeding, regardless of whether the black hole originated from a light or heavy seed,” says Suh.

The discovery of LID-568 also shows that it’s possible for a black hole to exceed its Eddington limit, and provides the first opportunity for astronomers to study how this happens. It’s possible that the powerful outflows observed in LID-568 may be acting as a release valve for the excess energy generated by the extreme accretion, preventing the system from becoming too unstable. To further investigate the mechanisms at play, the team is planning follow-up observations with JWST.

Reference: “A super-Eddington-accreting black hole ~1.5 Gyr after the Big Bang observed with JWST” 4 November 2024, Nature Astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02402-9

The team is composed of Hyewon Suh (International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab, USA), Julia Scharwächter (International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab, USA), Emanuele Paolo Farina (International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab, USA), Federica Loiacono (INAF – Astrophysics and Space Science Observatory, Italy), Giorgio Lanzuisi (INAF – Astrophysics and Space Science Observatory, Italy), Günther Hasinger (Institute of Nuclear and Particle Physics/DESY/German Center for Astrophysics, Germany), Stefano Marchesi (INAF-Astrophysics and Space Science Observatory, Italy), Mar Mezcua (Institute of Space Sciences/Institute of Spatial Studies of Catalonia, Spain), Roberto Decarli (INAF – Astrophysics and Space Science Observatory, Italy), Brian C. Lemaux (International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab, USA, Institute of Astrophysics, Italy), Marta Volonteri (Paris Institute of Astrophysics, France), Francesca Civano (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA), Sukyoung K. Yi (Department of Astronomy and Yonsei University Observatory, Republic of Korea), San Han (Department of Astronomy and Yonsei University Observatory, Republic of Korea), Mark Rawlings (International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab, USA), Denise Hung (International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab, USA)