This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning. Explore all of our newsletters here

Welcome back. Trump: a second chance? was the title of a BBC documentary this week on the US elections. It ended with Robert Reich, the Clinton administration’s labour secretary in the 1990s, telling an interviewer: “Wish us luck. By us, I mean the United States.”

In all the time I’ve followed US presidential elections (the earliest I remember is the Nixon-Humphrey-Wallace contest of 1968), I have never until now heard a respected, middle-of-the-road public figure such as Reich ask for America’s friends to wish the country luck.

But Europeans know what he means. You can find me at [email protected].

Democracy in peril?

The contest between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump makes Europeans nervous for at least three reasons: democracy, defence and economics.

Let’s take democracy first.

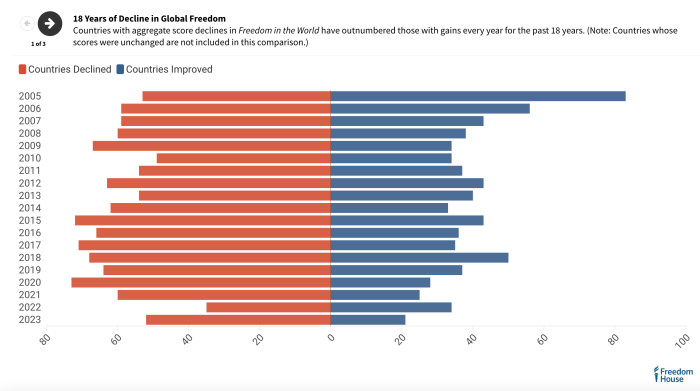

In the latest edition of its annual report on freedom around the world, the non-partisan, US-based group Freedom House said that political rights and civil liberties had deteriorated in 52 countries last year, while only 21 countries had registered improvements.

Its conclusion was that global freedom had declined in 2023 for the 18th consecutive year.

Then the organisation linked these findings to Tuesday’s US elections:

As it has for decades, the US can play a vital role in the expansion of global freedom.

But much depends on whether the November 2024 presidential election reinforces or weakens America’s democratic values, processes and institutions, along with its will to uphold the cause of democracy around the world.

Writing for Social Europe, Harold James, a Princeton University historian, makes a similar point:

No one knows how the US presidential election will turn out. One possibility is that the Trump bubble will finally burst, allowing for a return to normalcy in America and around the world.

But it is also possible that the United States will lurch toward a radical militarised authoritarianism that would establish a new norm for despots elsewhere.

This is Europe’s most profound concern. If democracy were to stumble in its US stronghold, it would stimulate illiberal or extremist political forces that are already active — in some countries, even in or close to government — in Europe.

It would also make European democracies more isolated and vulnerable in a world where dictatorships and semi-authoritarian regimes are contemptuous of liberal norms and act aggressively to discredit them.

Defending Europe

Europe’s second worry is defence and security.

Many Europeans lose sleep at night at the prospect that Trump might act or speak in ways that would shatter the credibility of the US security guarantee of Europe, expressed through Nato and the nuclear umbrella.

European supporters of Ukraine also worry that he might try to settle the war there on terms that amounted, in effect, to a victory for Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Some politicians recognise that, in certain respects, Europe has only itself to blame. Many governments have spent too little on defence for far too long (though military budgets are rising), and a united EU foreign policy is more an aspiration than a reality.

In this piece for Project Syndicate, Friedrich Merz, leader of Germany’s opposition Christian Democrats, laments what he calls “the desolate state of European foreign and security policy at a critical moment”.

Most Europeans would certainly feel more comfortable with Harris in the White House, as is shown by surveys such as this one by the Savanta data and market research company.

In six countries polled — France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain — clear majorities thought Harris would be better for Europe’s security.

Change things so things stay the same

However, that is not the whole story — as is made clear in an impressive collection of commentaries issued by the US Council on Foreign Relations and associated think-tanks.

For instance, Patrycja Sasnal of the Polish Institute of International Affairs writes:

Harris as president [would epitomise] a generational change in American politics that [would mean] shifts and challenges for Europe, too.

. . . with US President Joe Biden we bid farewell to post-cold war politicians, viscerally connected with European countries for better or worse, who have regarded the transatlantic partnership with a semi-religious dogma.

With Harris, Europe [would] have to embrace a new United States, more West coast, deeply connected to Asia and Latin America, perhaps at the expense of the partnership with Europe.

We can learn something about how a Harris administration might act on the international stage by considering the career and outlook of Philip Gordon, her chief foreign policy adviser.

Writing for the Washington-based Center for European Policy Analysis, Samuel Dempsey says:

Gordon . . . has broad expertise in Europe, is firmly behind Ukraine, but has advocated for a European Nato that pays its way.

Europeans hoping that a Harris administration might return to the good old days where the US pays a lot and asks little in return will likely be disappointed.

In other words, whoever wins the presidency, Europe will have to get its act together if it wants to preserve its freedom and, one hopes, remain allied with the US.

Economic threats

A third concern for Europe is trade and the economy.

At a rally in Pennsylvania this week, Trump could hardly have sounded more menacing about what lies in store for the EU on the trade front, if he should return to the White House:

I’ll tell you what, the European Union sounds so nice, so lovely, right? All the nice European little countries that get together …

They don’t take our cars. They don’t take our farm products. They sell millions and millions of cars in the United States. No, no, no, they are going to have to pay a big price.

The prospect of a Trump victory, followed by punitive US tariffs on European goods, is hurting the share prices of export-sensitive companies such as Diageo, LVMH and Volkswagen, the FT reported this week.

For sure, the EU has been working on a response. As my colleague Henry Foy wrote:

The [European Commission], which manages trade policy, has already drafted a strategy to offer Trump a quick deal on increasing US [exports] to the EU and only resort to targeted retaliation if he opts for punitive tariffs.

Not much better with Harris?

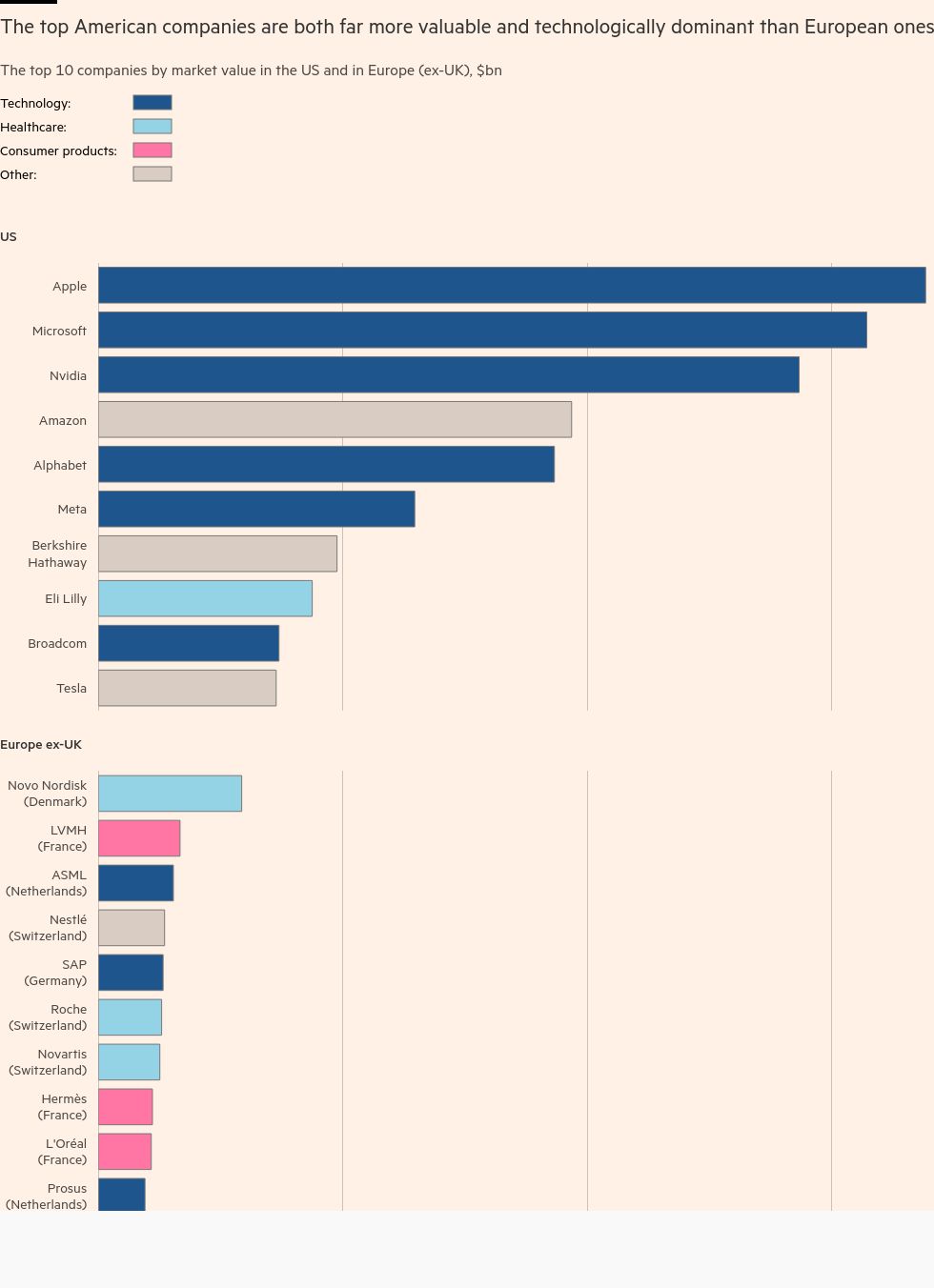

But the broader picture is that Europe has been falling behind the US — and, to some extent, China — in the technologies of the future (see the chart below).

Writing for the Centre for European Reform think-tank, Aslak Berg and Zach Meyers suggest that the EU might find Harris difficult to deal with on economic issues:

. . . while Harris would likely be more interested than Trump in transatlantic dialogue, both candidates have economic priorities which will put Europe in an awkward position — including getting tougher on China, and boosting US jobs in sectors sensitive to Europe, such as vehicle production.

Neither Republicans nor Democrats have been overly interested in European economic interests when they conflict with their domestic political priorities.

Who are Trump’s horse whisperers?

If Trump wins, who in Europe would be best placed, by temperament and political outlook, to talk to him?

That’s the question asked by Anchal Vohra in this well-judged piece for Deutsche Welle, the German broadcaster.

She mentions three figures — Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and Polish President Andrzej Duda — who, because they are on the hard right or national conservative side of the spectrum, might at first sight seem potential Trump horse whisperers.

But each throws up problems. Orbán speaks for almost no one else in the EU, not least because of his conduct during Hungary’s spell in charge of the bloc’s six-month rotating presidency.

As for Meloni and Duda, both are firm believers in Nato and the need to defend Ukraine — issues on which Trump sends shivers down Europe’s spine.

A more promising choice could be Mark Rutte, the former Dutch premier who is Nato’s new secretary-general. But he wouldn’t be able to speak on the EU’s behalf.

Truth to tell, it ought to be a German chancellor, a French president or both who would take on the challenge of dealing with Trump.

But Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s three-party German coalition seems close to giving up the ghost, and in any case who can forget the extremely difficult relationship that Trump had with former chancellor Angela Merkel?

As for President Emmanuel Macron of France, he has been much weakened by EU and national election results this year, and his term expires in 2027.

All in all, unsettling times lie ahead after Tuesday’s US vote. Hold on tight on election night!

To whom it may concern: America and Europe need each other — a New York Times column by Wolfgang Ischinger, a former German ambassador to Washington

Tony’s picks of the week

-

Thousands of North Korean soldiers are arriving in Russia to join Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine, but intelligence officials in Kyiv describe the majority of them as inexperienced, low-ranking foot soldiers, the FT reports

-

After a presidential contest and referendum that revealed Moldova to be politically split in two, next year’s parliamentary elections could put the country’s European integration on hold altogether, Ryhor Nizhnikau and Arkady Moshes write for the Finnish Institute of International Affairs

Recommended newsletters for you

FT Opinion — Insights and judgments from top commentators. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here