The aftershocks of a landmark tax-raising Budget were still reverberating late this week for the wealthy, who face a slew of tax increases on their savings and investments.

In her first Budget as chancellor, Rachel Reeves put a £40bn tax increase at the heart of a plan to fix the country’s “broken” finances.

Businesses and the wealthy will bear the brunt of Labour’s measures, with higher taxes on employment, shares and pension wealth.

The wealthy weren’t the only group unnerved by the scale of the Budget measures. Gilt yields climbed as investors took fright at Reeves’ plans for additional borrowing to “fix the foundations” of the economy.

FT Money sets out the Budget’s key tax-raising measures and what they mean for your finances.

Tax

The biggest tax-raising Budget since 1993 brought fundamental changes for businesses and asset owners.

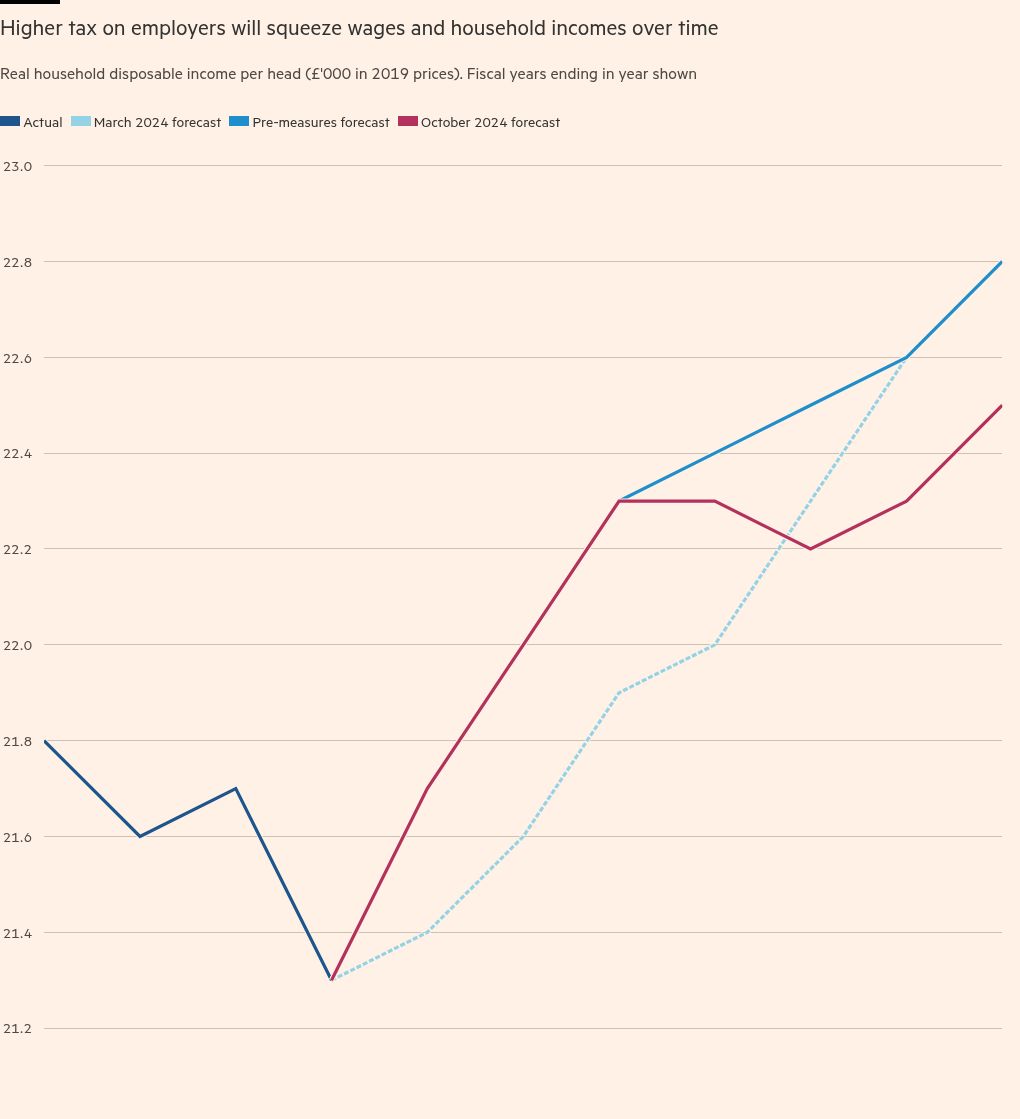

The big-ticket tax rise was a 1.2 percentage point increase to employers’ national insurance and a lowering of the threshold at which businesses start to pay the levy from £9,000 to £5,000.

The government was at pains to present this move as a tax on business, rather than on the “working people” the Labour manifesto promised to protect.

However, economists warned the tax rise will ultimately be passed on to workers and consumers through lower wages and higher prices. And the Institute for Fiscal Studies argued on Thursday that the changes would increase the risks of job losses for low-paid staff.

Owners of small businesses are also unhappy about the tax rises, which come alongside a boost for the national minimum wage and workers’ rights.

Gareth Morgan, chief executive of Balance, a digital marketing agency and consultancy, said he knew employers who would be less likely to take on workers due to the tax rises. He would be factoring it into his own growth plans based on headcount.

“The government should be doing something to encourage small businesses rather than push them away. Small businesses are what helps the overall economy grow,” he said.

There were also warnings about the impact the employer national insurance rise would have on roughly 700,000 freelance contract workers who use umbrella companies.

These are payroll agencies that take on a contractor’s financial administration, managing their tax and pay. But the umbrella industry is unregulated and experts warn there are scams as well as legitimate operators.

Myron Jobson, senior personal finance analyst at Interactive Investor, said: “In most cases, the umbrella company employs a freelancer/contractor and pays their wages through PAYE. As such, the increase in NI for employers threatens to reduce the take-home pay for hundreds of thousands of freelancers.”

Investors were another group targeted by the chancellor, with a rise in the lower rate of capital gains tax (CGT) from 10 per cent to 18 per cent, and from 20 per cent to 24 per cent for the higher rate. The change brings the higher rate in line with the rate on property assets.

And in another hit to entrepreneurs, the rate of CGT that applies to assets qualifying for business asset disposal relief (BADR) will increase from 10 per cent to 14 per cent for disposals made on or after April 6 2025.

Some commentators criticised the erosion in BADR. The relief was once worth £1mn in CGT savings. From April 2026, it will be worth a maximum of £60,000.

“The changes to NIC, CGT and BADR will ultimately impact small business owners and the competitiveness of the UK,” said Simon Gleeson, partner at Blick Rothenberg, an accountancy firm.

But a feared removal of inheritance tax relief on Aim-traded shares, used by some investors to mitigate IHT, only partially materialised. From April 2026, relief on Aim shares will be capped at 50 per cent, resulting in a 20 per cent effective tax rate.

Business owners, landowners and farmers were also hit by caps to two key inheritance tax reliefs. Agricultural relief (APR) and business property relief currently provide up to 100 per cent inheritance tax relief on the transfer of farm and business assets. However, from April 2026 Reeves said the two reliefs will be capped on business and agriculture assets worth more than £1mn.

Assets beyond that level will receive 50 per cent relief — again, an effective tax rate of 20 per cent for beneficiaries. People may still benefit from existing exemptions and spousal transfer relief, which in certain cases could result in an additional £1mn allowance among spouses.

Emily Deane, technical counsel and head of government affairs at the Society of Trust and Estate Practitioners, a professional body, said: “This will come as a huge shock to agricultural businesses that have limited cash flow and may result in financial strain on family businesses and farms being forced to sell. In reality, most farmhouses with barns and acres of land to farm on will be valued at £1mn-plus.”

Others downplayed the impact. Dan Neidle, founder of think-tank Tax Policy Associates, said fewer than 500 farms a year were likely to pay more tax, pointing to government statistics that showed that around this many farms claimed more than £1mn APR in 2021-22.

Wealthy foreigners face the abolition of the non-dom regime, to be replaced with a new residence-based system that will apply over four years rather than the current 15.

The measure is forecast to raise £12.7bn over the next five years. As part of the wider move to abolish the non-dom regime, the government also confirmed it would end the use of trusts to shelter assets from UK inheritance tax from April 2025.

However, several concessions designed to sweeten the pill for existing non-doms were contained buried in the Budget documents. These revealed that non-doms’ trusts set up before Budget day will not be subject to a 40 per cent inheritance tax on the death of the person setting them up, as many had feared. Instead, the trust will pay inheritance tax at a rate of 6 per cent every 10 years.

Meanwhile, several smaller announcements — which nevertheless could have an outsized negative impact on those affected — were buried in the Budget detail.

These included the scrapping of a planned reform to the controversial high income child benefit charge, which would have allowed more parents to claim the benefit.

Labour also announced an increase in the late payment interest rate for tax debt by 1.5 percentage points to 9 per cent.

Pensions

One of the most significant Budget changes for wealthier retirement savers was on pensions, which will be brought into inheritance tax from April 2027.

Since the pension freedoms of 2015, inheritance tax planning has often been built around the recommendation that individuals withdraw their pension last — after other savings and investments — because of an inheritance tax exemption.

But that has now been turned on its head, with inherited defined contribution pensions potentially liable to a double whammy of both income and inheritance tax from April 2027.

“This will change how people view their pensions,” said Tom McPhail, director of public affairs at consultancy The Lang Cat. “The long-term benefits of substantial pension pots have become very questionable.”

Pensions passed to a spouse or civil partner will continue to be exempt from IHT. But those not qualifying for this could see up to two-thirds of an inherited pension pot wiped out under the changes.

If a pensioner dies after age 75, from April 2027 their unspent pensions could be subject to 67 per cent tax if inherited by an additional rate taxpayer. Tax charges would be 52 per cent if the beneficiary is a basic rate taxpayer, due to the combined effect of both IHT and income tax.

These calculations are based on an inheritance tax charge of 40 per cent. Beneficiaries pay income tax at their marginal income tax rate, which is 20 per cent for basic rate taxpayers, 40 per cent for higher and 45 per cent for additional.

For people with large pension pots over the age of 75, Andrew King, retirement planning specialist at Evelyn Partners, said they might consider taking money out to gift or spend, perhaps on a regular basis, if they want to lower their potential tax bill.

Advisers also expect the changes to lead to a surge in people taking out annuities — particularly for spousal transfers — as they will look “more attractive to optimise the lifetime value of the money” rather than face a double tax charge, said McPhail.

People may also use pension money to buy whole of life insurance policies, which provide a payout to a policyholder’s family or estate when they die. This could help people who own businesses or farms now facing higher inheritance tax bills after cuts to available relief.

According to Budget documents, pension money left to charity will be exempt from inheritance tax, but lump sum “death in service benefits” — provided by employers to the family or dependants of an employee who dies while in service — will not.

“This is one change that worries us most,” said Jeremy Harris, partner at law firm Fieldfisher. “It appears to be catching people of working age who die unexpectedly.”

John Greer, head of retirement policy at Quilter, warned that accessing inherited pensions on death is likely to take longer, with the ability to use a pension to pay for probate — the legal process of dealing with a deceased person’s estate — now removed.

“This stuff is complicated. I think it’s going to drive more people to financial advice,” he said.

Property

Property investors said that one contentious tax-raising measure — the decision to increase by two percentage points the stamp duty surcharge on property transactions for second homes — would further constrain the supply of available private rented properties.

The National Residential Landlords’ Association (NRLA) and some other groups said the rise would deter landlords from expanding their portfolios, meaning fewer homes would be available to rent.

The chancellor increased the surcharge on stamp duty on second home

purchases to 5 per cent, from 3 per cent. On the highest-rate purchases — above £1.5mn — the duty on such purchases will rise to 17 per cent.

Chris Norris, campaigns and policy director of the NRLA, said the higher cost would prompt landlords to put their money into other, less risky investments instead of houses. That could mean more homes end up in the hands of owners who will not rent them out.

“What you have to look at when you’re considering supply in the private rented sector is the availability of homes to people who need them,” Norris said.

The chancellor is also allowing the lapse of a scheme introduced in 2022 to reduce the stamp duty paid by first-time buyers. The exemption took first-time purchasers out of stamp duty on the first £425,000 of a purchase’s value and charged them only 5 per cent on the value of deals between £425,000 and £625,000. The relief will be allowed to expire after March next year.

Despite the end of the relief, Generation Rent — a campaign group representing private renters — partially supported the chancellor’s stance on stamp duty.

Chief executive Ben Twomey said higher costs for investors “will make it easier for first-time buyers to compete in the house sales market”.

Treasury figures predicted the higher surcharge would lead to an additional 130,000 purchases by first-time buyers or buyers of primary residences over the next five years.

Generation Rent also welcomed planned changes in the social housing sector, restricting tenants’ right to buy houses they rent. Twomey called the changes “steps in the right direction”.

However, Norris said the idea that the higher surcharge would free up properties by giving first-time buyers an advantage was “simplistic”, saying there was a “swath” of people who could not currently afford to buy who would lose out if private sector landlords were put off buying.