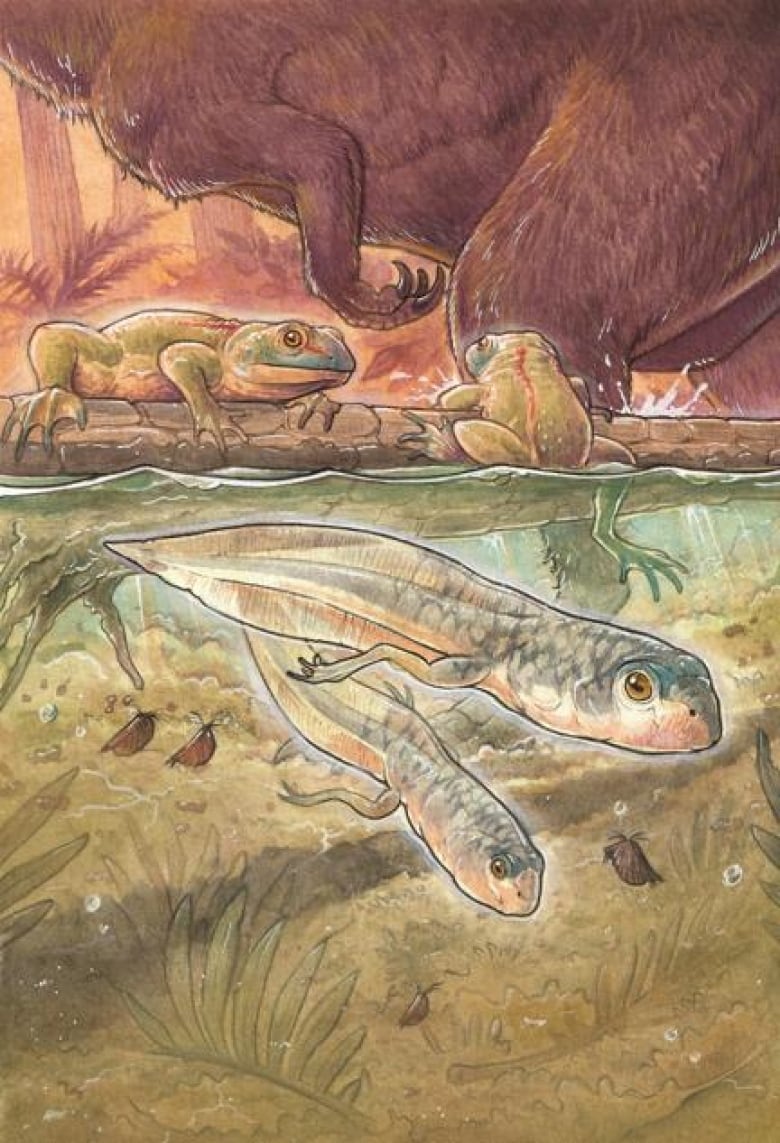

Scientists have discovered the oldest-known fossil of a giant tadpole that wriggled around over 160 million years ago, among the dinosaurs of the Jurassic Period.

The new fossil, found in Argentina, surpasses the previous ancient record holder by about 20 million years.

Imprinted in a slab of sandstone are parts of the tadpole’s skull and backbone, along with impressions of its eyes and nerves.

“It’s not only the oldest tadpole known, but also the most exquisitely preserved,” said study author Mariana Chuliver, a biologist at Maimonides University in Buenos Aires.

The specimen, belonging to a previously known species called Notobatrachus degiustoi.

The fossil was found in 2020 during a dig for dinosaur remains on a ranch in the province of Santa Cruz, about 2,300 kilometres south of Buenos Aires in Argentina’s vast southern Patagonian region.

Researchers know frogs were hopping around as far back as 217 million years ago. But exactly how and when they evolved to begin as tadpoles remains unclear.

This new discovery adds some clarity to that timeline. At about a half-foot (16 centimetres) long, the tadpole is a younger version of an extinct giant frog. (The American bullfrog, the largest living frog in Canada, reaches a maximum of 20 centimetres, and most other species are much smaller.)

“It’s starting to help narrow the timeframe in which a frog becomes a frog,” said Ben Kligman, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History who was not involved with the research.

The results were published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The fossil is strikingly similar to the tadpoles of today — even containing remnants of a gill scaffold system that modern-day tadpoles use to sift food particles from water.

That means the amphibians’ survival strategy has stayed tried and true for millions of years, helping them outlast several mass extinctions, Kligman said.