Latest news on ETFs

Visit our ETF Hub to find out more and to explore our in-depth data and comparison tools

Low- and minimum-volatility funds are haemorrhaging money as performance continues to disappoint and investors shift to a newer, shinier way of managing risk in equity markets.

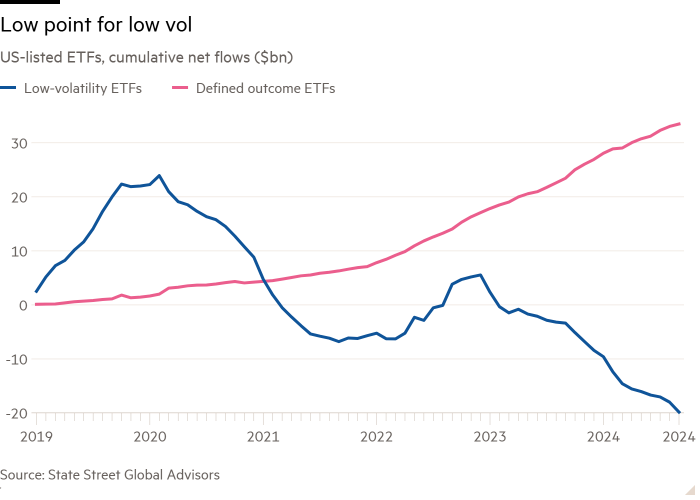

Investors have pulled $43.8bn from US-listed low-volatility exchange traded funds since February 2020, according to data from State Street Global Advisors, with just one month of positive flows in the past 22.

Money is instead pouring into newer “defined outcome” buffered ETFs, which use derivatives to reduce the risk of investing in equity markets, and which have attracted $31.5bn over the same period.

“There has been a clear trend of growing usage of defined outcome ETFs and a reduction of interest in using low-volatility exposures in portfolios,” said Matthew Bartolini, head of Americas ETF research at SSGA. “They are definitely in competition.”

Bryan Armour, director of passive strategies research, North America at Morningstar, added “low-volatility ETFs and buffer ETFs both seek to lower the risk of investing in stocks. In that way they are substitutes [for each other].”

The concept of minimum volatility is based on an anomaly first identified by economists Fischer Black and Myron Scholes in the 1960s, who found that portfolios based on the least volatile stocks tended to outperform the market, possibly because investors overpay for more exciting stocks.

However, returns have been poor in recent years, with outperformance in 2022, when equity markets fell, paling compared with massive underperformance in 2020 and 2023, alongside undershoots in 2021 and so far this year.

The iShares MSCI USA Minimum Volatility ETF (USMV), by far the largest such vehicle with $24.2bn of assets, has generated an annual average return of 9.3 per cent over the past five years, comfortably below the 15.9 per cent of the underlying MSCI index, and worse than the returns generated by iShares’ ETFs tracking other smart beta factors, such as momentum, quality and (small) size, although a fraction better than its value ETF.

Bartolini traces the start of the rot for low-volatility funds to the market crash in 2020 when Covid-19 hit and the subsequent rally.

“The events of 2020 seem to be the inflection point where this trend accelerated,” he said. “Assets started falling after the pandemic started and correlations moved to one. Everything fell: low-volatility equities are still equities, they still fell.

“And of course they lagged on the upside because it was a high-beta rally and they hold low-beta stocks. You captured all the downside but none of the upside,” Bartolini added.

This underperformance has broadly continued since, not helped by the fact that Wall Street’s gains in the past two years have been led by technology stocks, which low-volatility ETFs tend to underweight: none of the Magnificent Seven US market heavyweights appear among USMV’s 15 largest holdings.

A strong market backdrop also reduces the incentive for safety-first equity investing.

“We are in a year when the S&P 500 is up more than 20 per cent, so this is a tough year for a low-risk strategy to succeed,” said Todd Rosenbluth, head of research at TMX VettaFi, a consultancy.

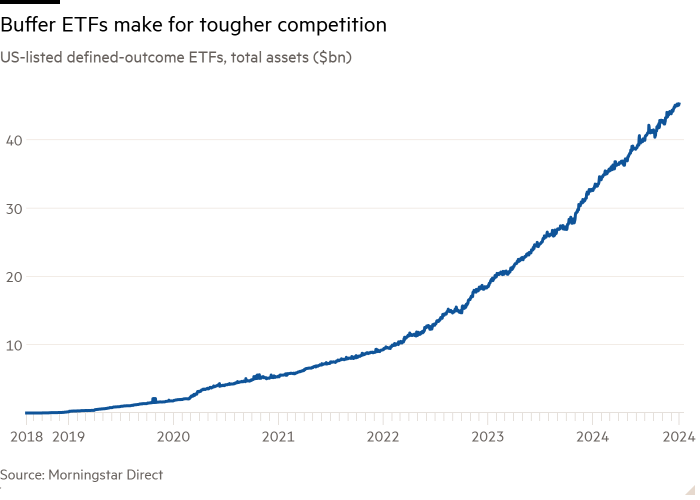

Compounding this issue has been the rise of defined-outcome ETFs, which now have total assets of $45bn in the US, according to Morningstar Direct. These funds provide limited upside potential but largely shield investors from losses, typically protecting against the first 10-20 per cent of losses in a 12-month period.

“That has become desirable for those who want to manage the risk profile of their equity book,” Bartolini said, with more “intuitive” outcomes meaning “the pay-off structure is a little bit clearer”.

“Options-based ETFs make it relatively easy to control your destiny and limit the downside with hard protection targets, so I think some of the demand that might have gone into minimum or low-volatility ETFs has instead gone to defined-outcome ETFs,” said Rosenbluth.

However, the competing fund structures offered different experiences, Rosenbluth added, with the upside capped in buffered ETFs, but not in low-volatility ones.

Analysis by Armour found that buffered ETFs offering 10 per cent protection had a similar beta to low-volatility ETFs, roughly 0.6 over the past five years. Vehicles offering greater protection were, not surprisingly, lower beta still, at 0.45 for ETFs with 15 per cent protection and 0.37 for those with 20 per cent, meaning “buffer ETFs have had better risk-adjusted performance than low-vol ETFs”, Armour said.

“Overall, I’d expect low-volatility ETFs and lightly buffered ETFs to perform somewhat similarly over a full cycle. Low-vol ETFs benefit from having better upside while lighter-buffer ETFs might face similar losses to a low-vol strategy in an extreme downturn.

“Those ‘tail’ events should give low-vol strategies an edge over the long run,” added Armour, who noted that they also tended to be far cheaper.

Bartolini also believed low-volatility ETFs still had a role to play and could potentially benefit from tactical inflows if market volatility rose.

Rosenbluth agreed, given his perception that the original thesis for min vol — that it outperforms the broader market over the cycle — probably still held.

If that is the case, investors parked long term in buffered ETFs, which most observers will underperform over the cycle, might be missing a trick.