This article is an on-site version of our Chris Giles on Central Banks newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Tuesday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

The annual meetings of the IMF are always a good time to take stock of the global economy and the policy positions of leading countries. Last week’s jamboree in Washington was no exception. What struck me most was not the general angst about a Trump victory — that was inevitable. It was the otherworldliness of the IMF’s main economic policy advice.

There is no doubt what this advice was. The World Economic Outlook (WEO) report was titled “Policy pivot, rising threats”, and the three pivots it called for were as follows. First, an easing of monetary policy, which the IMF recognised was already under way. Second, a sustained and credible multi‑year fiscal adjustment to address the “urgent” need to stabilise government debt dynamics and rebuild fiscal buffers. Third, it called for growth-enhancing structural reforms.

Since the IMF always, rightly, calls for growth-enhancing structural reforms, I will focus on its recommendation of monetary loosening alongside fiscal tightening. This is new.

The table below shows the development of monetary and fiscal policy advice in successive autumn and spring IMF meetings. No need for ChatGPT here. It is surprisingly easy to summarise its advice in a maximum of two words.

The IMF’s monetary advice has tended to mimic the policies of central banks and might even be a description of what is happening rather than advice. Fiscal policy advice from the IMF has moved in a linear fashion from a recommendation of stimulus during the coronavirus pandemic towards ever louder calls for policy tightening.

The IMF is not asking countries to go crazy with tax increases or public spending cuts. Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, the fund’s chief economist, said a balance had to be struck between short-term demand destruction if countries slammed on the fiscal brakes and the risk of disorderly adjustments if they did too little and countries lost access to bond markets. “Success requires implementing, where necessary, and without delay, a sustained and credible multi‑year fiscal adjustment,” he said.

According to the IMF, the benefits of this pivot from monetary to fiscal tightening is a “favourable feedback loop” in which inflation remains under control as interest rates come down, easier monetary policy supports demand growth and eases the costs of government borrowing, this facilitates fiscal consolidation and then further monetary easing. In combination, the IMF concludes, “tighter fiscal policy paves the way for looser monetary policy”.

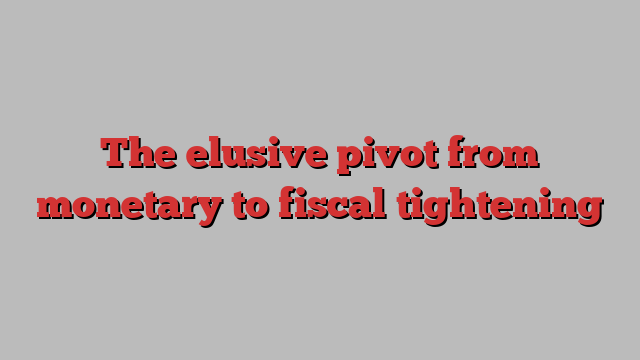

There is little doubt that interest costs have been rising as a share of government revenues and this is increasingly a problem for finance ministries around the world, so the IMF has touched on an important problem.

Let us see if this pivot is happening in the real world.

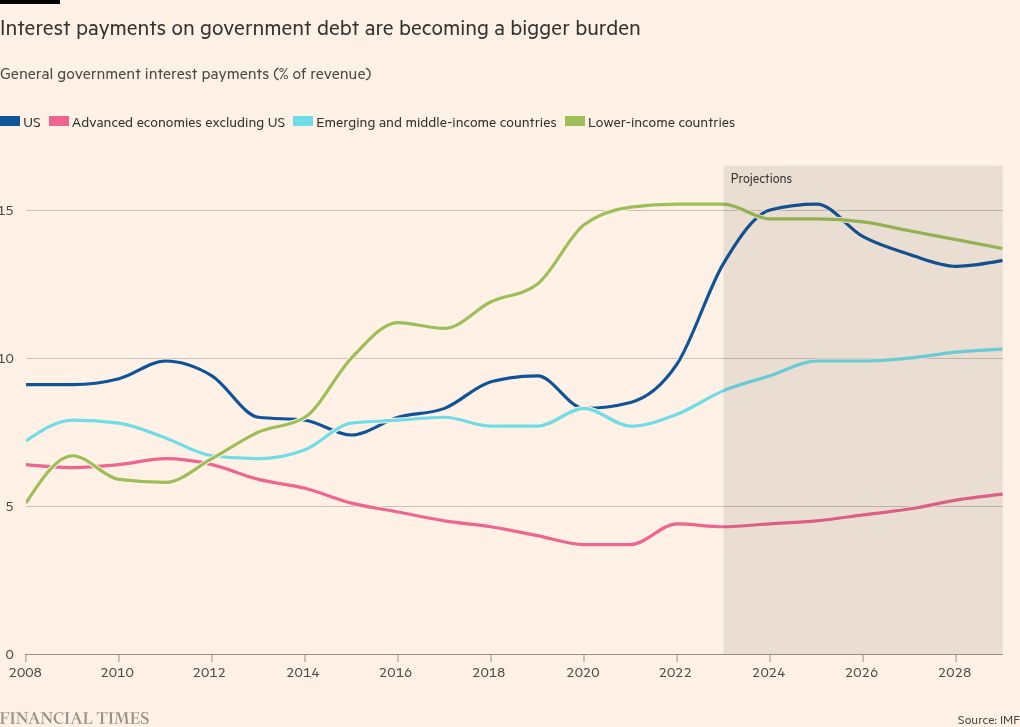

On the monetary side, there are clear signs that progress with disinflation has allowed central banks to ease nominal interest rates. Whether you like the concept of short-term real interest rates or not, these have continued to rise in 2024 when rates had previously been stable because they came with falling year-ahead inflation expectations. The IMF explains that real rates are expected to come down alongside nominal rates as inflation expectations stabilise.

The chart below shows the discretionary and non-discretionary monetary tightening phases along with market forecasts for the US and Eurozone. The monetary policy pivot is happening.

What about fiscal policy?

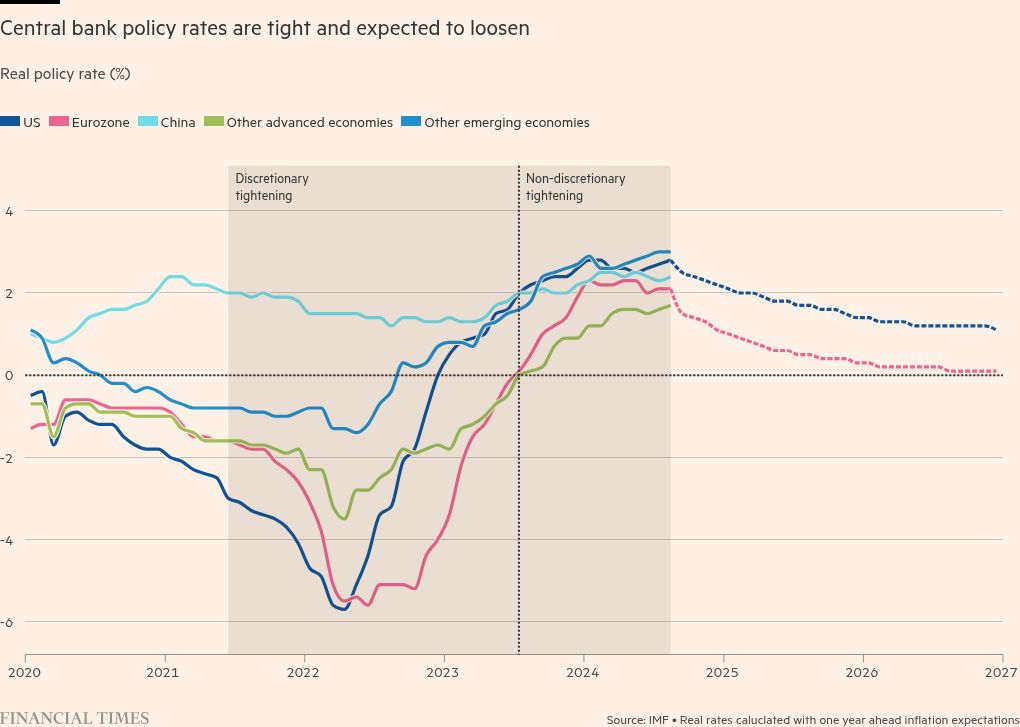

It is right for the IMF to give recommendations, but I am afraid to say there is next to zero sign that the finance ministries of the world were listening last week.

There is not much sign that the IMF really believes it either. Almost every G7 country has a higher projected structural budget deficit in 2029 than in 2019 before the pandemic, with huge loosening in France and Italy. The US structural deficit is marginally lower in 2029 than in 2019, but huge in both years. The forecast for 2029 is also based on the IMF’s forecast policy assumption that countries do follow the fund’s advice to some extent. There is not much fiscal tightening baked into the 2024 to 2029 forecasts either.

More telling is that the fiscal outlook of structural deficits is worse in this October’s edition of the WEO compared with earlier editions. The chart below compares the most recent forecast with those made in the April 2022 WEO.

That fiscal pivot is simply not happening.

To the extent that the fiscal pivot does not happen as the IMF hopes, it suggests that government borrowing costs are likely to remain higher and that monetary policy probably cannot and should not loosen as much as financial markets expect. That is, unless, a lot more stimulus is generally needed than the IMF thinks.

Whatever happens, the IMF is likely to become ever more shrill with its fiscal policy message in future as countries merrily ignore it.

The UK isn’t pivoting

The first country to ignore the IMF’s advice will be the UK on Wednesday when the newish Labour government delivers its first Budget. Since ministers do not want a big surprise on the day, we know it will increase taxes, public spending and government borrowing.

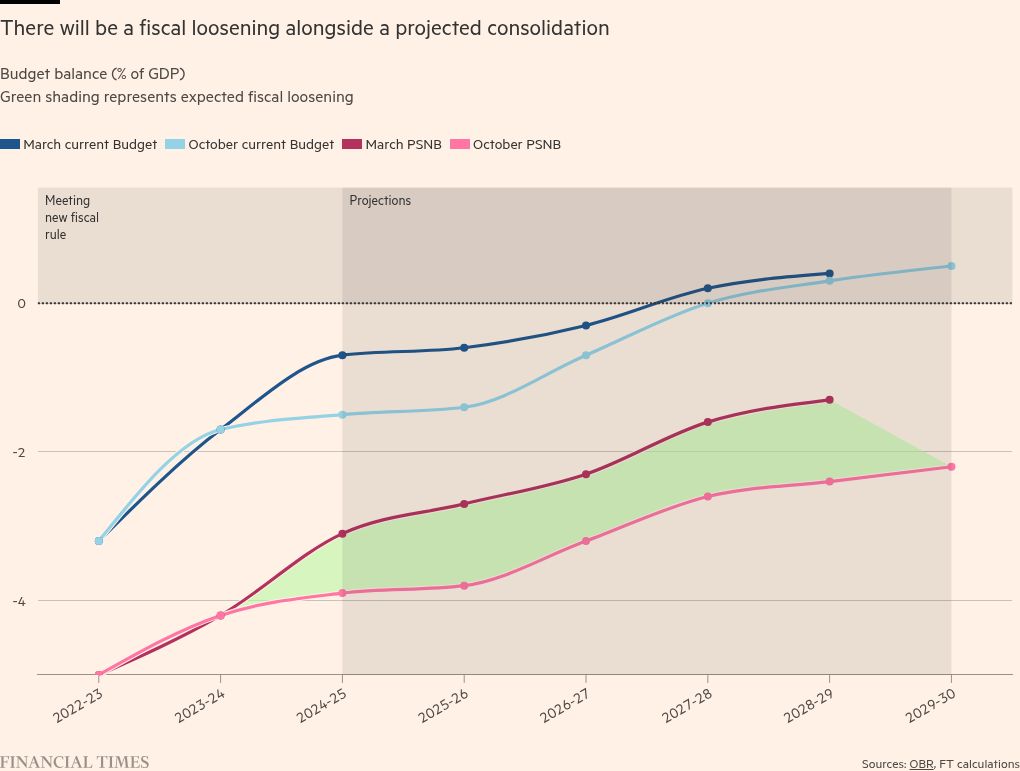

Below are my predictions for the new government borrowing forecasts along with those from the previous March Budget. These are falsifiable and I promise to come back next week with a mea culpa if they are horribly wrong.

I expect the new binding fiscal rule will be balancing the current budget (excluding net investment), which will be projected by the end of the decade. So, there is a budgetary consolidation planned.

But there is also a significant fiscal loosening, with overall public sector net borrowing (PSNB) likely to be about 1 per cent of GDP higher as the UK government plans to increase day-to-day public spending growth and public investment. Tax rises will also be large — about 1.5 per cent of GDP annually — by the end of the decade.

What should the Bank of England make of this? The Budget will increase actual and projected borrowing, this will stimulate demand, higher investment will improve supply, tax rises will detract from supply and there will be an ongoing fiscal consolidation.

Another falsifiable prediction of mine is that the BoE is likely to say these changes will make little difference to projected monetary policy. This is what happened in MPC meetings after other recent Budgets that loosened the fiscal stance. I am thinking of the May 2023 MPC meeting, the December 2023 meeting and the March 2024 meeting.

That said, I once suggested privately to one MPC member that the committee likes to find reasons why fiscal policy does not matter. I came away with a flea in my ear, having been roundly told off.

What I’ve been reading and watching

-

The Bank of Canada goes large with a half-point cut in rates

-

The Chinese economy shows ever more signs of strain — this time with falling industrial profits

-

Europe is preparing for a Trump victory with plans for tariff retaliation. Not wise, says Alan Beattie, because it is better to do a deal with the former president, even if you have no means of undertaking the commitments you have made to buy US stuff

-

Central bankers in advanced economies should spare a thought for their counterpart in Bangladesh. Governor Ahsan Mansur, who got the job after the regime of Sheikh Hasina was toppled in August, has accused tycoons of “robbing banks” of $17bn in the country

A chart that matters

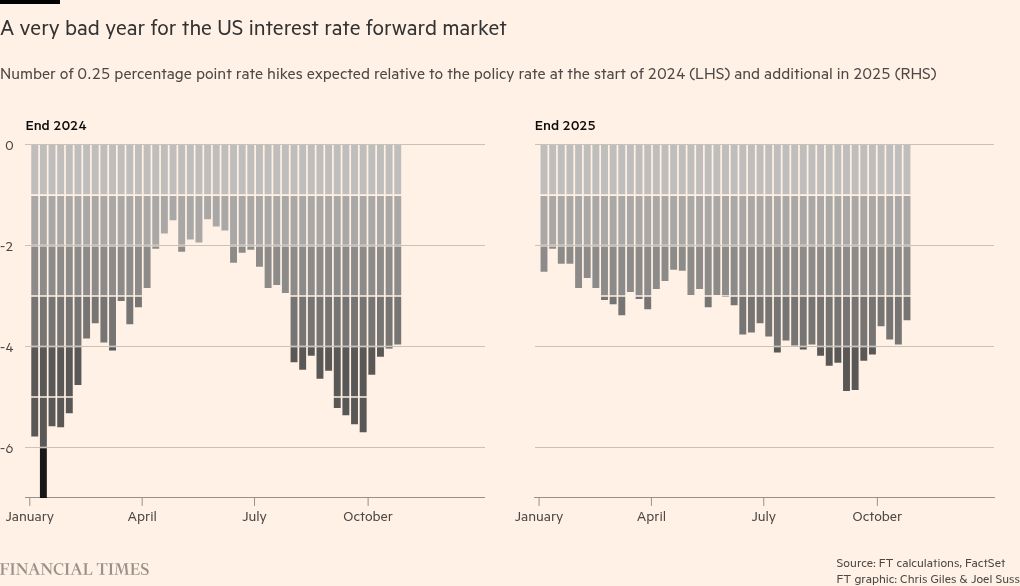

Ever wondered how good financial markets are at predicting US interest rates? This year, they have been all over the place, starting the year predicting six quarter-point cuts, reducing that to one-and-a-half by April and going back to six in September. Now it is four.

Let me know if you think this is an efficient market, carefully processing the available information? I’m at [email protected]

Recommended newsletters for you

Free lunch — Your guide to the global economic policy debate. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here