France’s luxury, defence, and construction blue-chip companies are among those set to face significantly higher tax bills under a new belt-tightening budget that will dent their profitability this year and next.

LVMH, the Paris-based luxury powerhouse controlled by Bernard Arnault, expects to pay an additional €700mn to €800mn in corporate tax this year, an increase of about 15 per cent on the €5.7bn it paid last year. Vinci, the infrastructure group that operates toll roads in France, will pay an extra €400mn, or 18 per cent, in taxes.

While lawmakers are still debating the budget, meaning that details can still change, executives have warned that higher corporate taxes and other policy changes will reverse seven years of business-friendly reforms undertaken by President Emmanuel Macron.

“The policies being proposed today will put us at the back of the pack again in Europe,” Alexandre Bompard, chief executive of food retailer Carrefour, told France Inter radio this month.

Premier Michel Barnier this month unveiled a €60bn fiscal package to address ballooning deficits through spending cuts and what he said will be “targeted and temporary” tax increases on companies and wealthy people.

About 400 corporations with over €1bn in revenues in France will be expected to pay more tax over two years to raise an estimated €8bn for state coffers, according to a draft budget.

Although Barnier has promised the extra tax will only last two years, companies and economists are sceptical since France has often gone back on such pledges and deficits will remain wide.

Sector-specific taxes will also be applied to airline tickets and maritime shipping groups to generate €2bn, and the government has proposed a tax on share buybacks to raise €200mn.

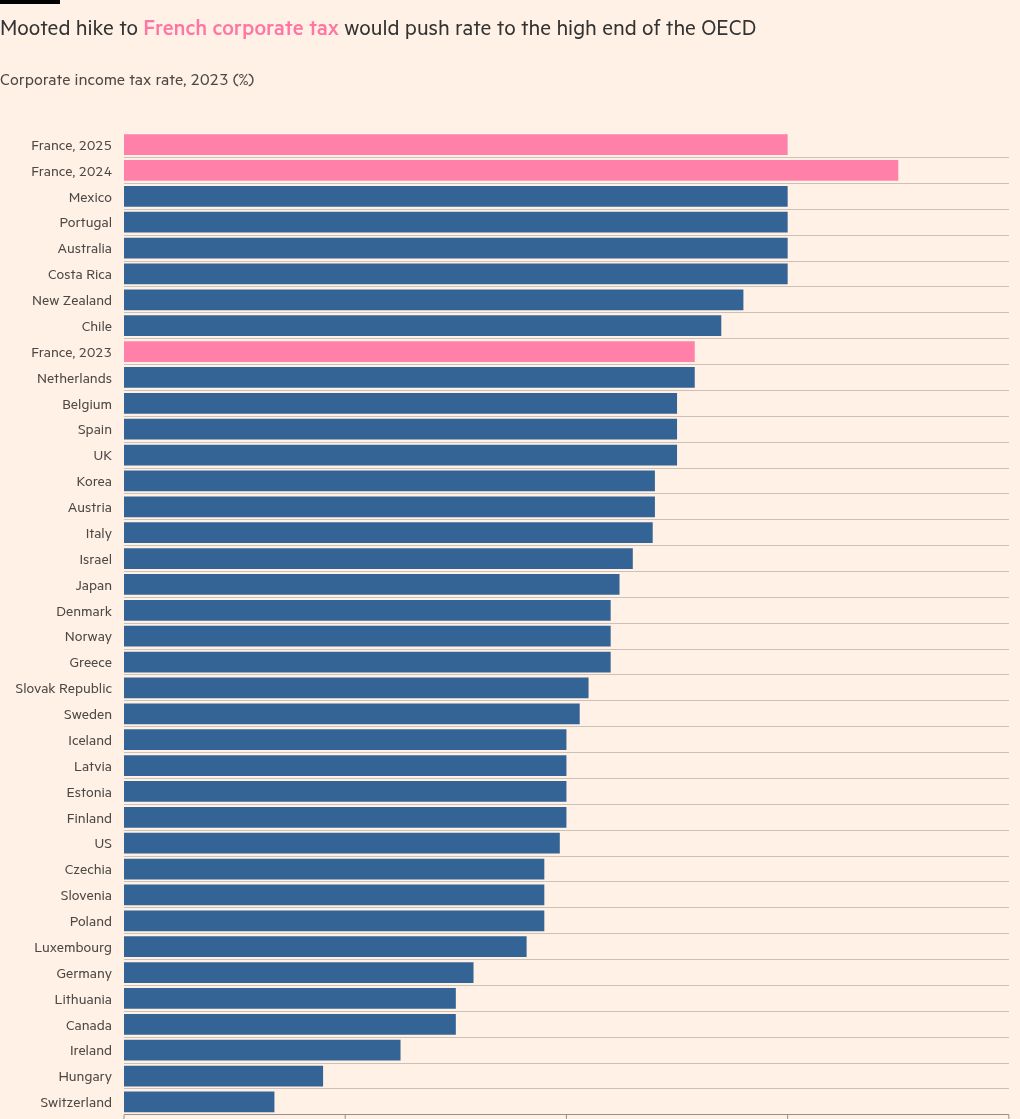

Macron enacted a gradual corporate tax cut starting in 2017 to take it from 33 per cent to 25 per cent. Some high profile chief executives have argued that Barnier’s proposal will send a negative image by penalising companies who conduct most of their business in France.

LVMH chief financial officer Jean-Jacques Guiony told analysts on a recent results call that the company pays about 40 per cent of its tax in France, so “nobody [should] feel that we’re not contributing to the budget effort that is currently under way.”

Rival luxury group Hermès said on Thursday that it expected to pay around €300mn in additional tax for 2024, a 19 per cent uplift from €1.6bn last year. Cosmetics maker L’Oréal has estimated that its tax bill will increase by €250mn this year.

“Your level of pain depends on the amount you sell in France and then how much profit made there,” said Thomas Zlowodzki, head of equity strategy at Oddo Securities.

Barnier, a conservative who leads an uneasy power-sharing government with Macron’s centrists, is relying significantly on tax hikes to narrow a budget deficit that is estimated to reach 6.1 per cent of national output this year, far above the EU target of 3 per cent.

Other measures in the budget, such a cutting subsidies for apprentices and low-wage workers, will also raise the cost of labour.

Economists have also warned that the plan, which aims to return the deficit to 5 per cent of GDP by the end of 2025, could cut economic growth to as low as 0.5 per cent next year, from an estimated 1 per cent in 2024.

An executive at a Cac 40 company said Barnier’s budget was “cowardly and misguided” because it is just “plugging holes in the short term” instead of instituting structural reforms to curb long-term spending.

Oddo estimated that the additional payments from companies with €1bn to €3bn in sales in France will raise their corporate tax rate from 25 per cent to 30 per cent for 2024, and 27.5 per cent for 2025. The rate for those with sales above €3bn will increase to 35 per cent in the first year and then dropping to 30 per cent, the financial services firm said.

The average statutory tax rate in the OECD when weighted for GDP is 25.8 per cent.

Aircraft engine maker Safran said on Friday that it expected additional taxes of €320mn to €340mn for 2024, which would cut its earnings per share by $0.75. Defence electronics group Thales said on Wednesday that it would pay roughly €105mn in extra tax for 2024 and 2025.

Broadcasters TF1 and M6, lottery company Française des Jeux, and airport operator ADP — all of which are heavily exposed to France — will end up with higher tax bills than larger companies such as oil major TotalEnergies, which earns very little of its profit in the country.

Luxury group Kering, owner of brands including Gucci and Saint Laurent, told analysts on Wednesday that it did not expect a significant impact on its tax rate because the “geographical footprint of our houses and of our production is concentrated in Italy.”

Shipping magnate Rodolphe Saadé said his CMA-CGM group expected to pay an additional €800mn over the two years. Global container shipping companies have long benefited from a favourable tax regime in which they pay depending on tonnage transported rather than profit.

Saadé told Le Figaro newspaper on October 21 that the supplemental tax represented a “consequential effort” for the group and that it “would pay out of patriotic spirit.” He warned that investment will take a hit if the government does not reverse the extra tax after two years as promised.

“If taxes increase, we will be less able to invest,” Saadé added. “Yet we need investment to remain competitive and stay among the best in the world.”

But Oddo’s Zlowodzki warned that the government would find other ways to extract more money from companies if deficits remained high, perhaps by permanently raising the corporate tax rate from the prior 25 per cent.

“As long as the budgets are so out of balance, there will be more tax one way or another on companies,” he said.

Additional reporting by Sarah White