Research reveals how antibodies affect brain receptors in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis, a condition often misdiagnosed as schizophrenia.

The disease, vividly described in Susannah Cahalan’s memoir “Brain on Fire,” can lead to severe neurological symptoms similar to those of mental health disorders. The study underscores the importance of personalized medicine and improved diagnostics to accurately treat and diagnose this rare disease.

The Startling Diagnosis of Susannah Cahalan

Imagine waking up in a hospital with no memory of the past month. Doctors inform you that you experienced a series of violent outbursts and paranoid delusions. You had even come to believe you were suffering from bipolar disorder. Then, after a specific test, a neurologist delivers a surprising diagnosis: a rare autoimmune disease called anti-NMDAR encephalitis. This was the reality for Susannah Cahalan, a New York Post reporter, who later wrote the best-selling memoir Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness about her experience.

According to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Hiro Furukawa, anti-NMDAR encephalitis can cause hallucinations, memory loss, and psychosis. It primarily affects women between the ages of 25 and 35—the same age range when schizophrenia often appears. However, anti-NMDAR encephalitis involves a different mechanism.

Key Insights on Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis

Furukawa, an expert in NMDARs, explains that these brain receptors are crucial for cognition and memory. In cases of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, antibodies attack these receptors, preventing them from functioning properly. This triggers an autoimmune response, causing brain inflammation—hence the term “Brain on Fire.”

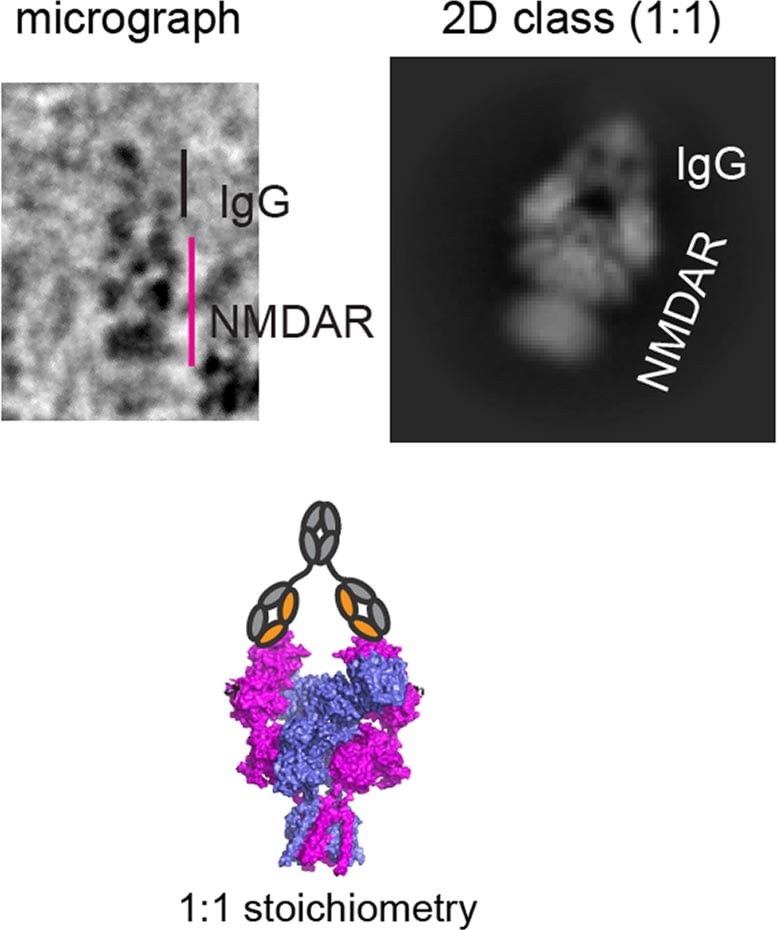

While some treatments are available, their effectiveness varies depending on symptom severity. New research from the Furukawa lab may explain why. In a recent study, Furukawa and colleagues map how antibodies from three patients bind to NMDARs. They find that the way in which each of the three antibodies binds to NMDARs differs. The discovery marks an important step in gaining a fuller understanding of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, a condition first diagnosed in 2008. Furthermore, it suggests personalized medicine may be critical for treating this disease.

Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment Innovation

“Distinct binding patterns manifest in different functional regulation levels in NMDARs,” Furukawa explains. “This affects neuronal activities. So, different binding sites may correspond to variations in patients’ symptoms.” Uncovering those correlations could lead to more precise therapeutic strategies. Imagine, for example, that scientists identify several binding sites common among encephalitis patients. Pharmacologists could then design new drugs to target these sites. But that’s not all. Personalized medicine could also mean more accurate diagnoses, Furukawa says.

“It’s still a rare disease, but it could be misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed. Therefore, we need to spread awareness. Could, for example, some schizophrenic patients have this disease? Could it be caused by antibodies?”

Broader Implications for Psychiatric Medicine

Currently, it’s said that anti-NMDAR encephalitis affects one in 1.5 million people. Yet, in time, we may find it’s more common than previously assumed. That’s a scary thought. However, it could explain why existing psychiatric medicine does not work for some people diagnosed with bipolar disorder and other mental health conditions—a huge revelation for patients as well as the families and therapists who care for them.

References:

“Structural and functional mechanisms of anti-NMDAR autoimmune encephalitis” by Kevin Michalski, Taha Abdulla, Sam Kleeman, Lars Schmidl, Ricardo Gómez, Noriko Simorowski, Francesca Vallese, Harald Prüss, Manfred Heckmann, Christian Geis and Hiro Furukawa, 3 September 2024, Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

DOI: 10.1038/s41594-024-01386-4

“Dendritic, delayed, stochastic CaMKII activation in behavioural time scale plasticity” by Anant Jain, Yoshihisa Nakahata, Tristano Pancani, Tetsuya Watabe, Polina Rusina, Kelly South, Kengo Adachi, Long Yan, Noriko Simorowski, Hiro Furukawa and Ryohei Yasuda, 9 October 2024, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08021-8

Funding: National Institutes of Health, Austin’s Purpose, Robertson Research Fund, Doug Fox Alzheimer’s Fund, Heartfelt Wings Foundation, Gertrude and Louis Feil Family Trust, German Research Foundation, German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Schilling Foundation