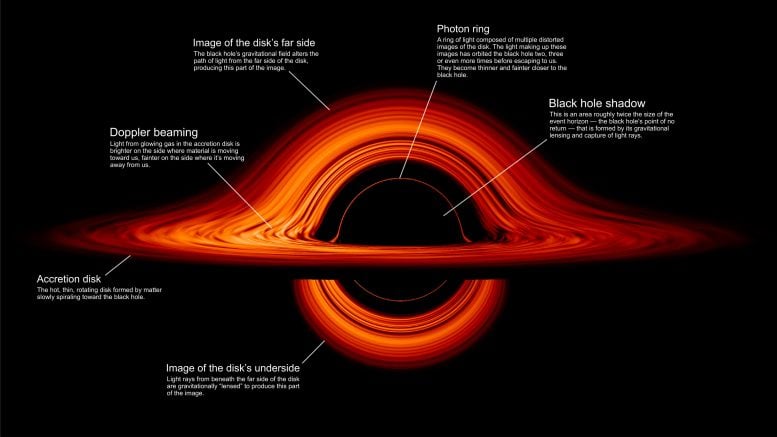

Black holes, with their event horizons trapping anything that enters, and accretion disks glowing from accumulated matter, present a fascinating study in extreme physics. As matter spirals into a black hole, it brightens and warps due to intense gravity, creating striking visual phenomena like the event horizon shadow and photon sphere. Additionally, the extreme environments near black holes produce powerful jets and a mysterious corona, which are key to understanding high-energy cosmic processes.

Event Horizon

The event horizon is what makes a black hole black. It is often described as the ‘surface’ of a black hole, though it is not a surface in the traditional sense. It is the critical boundary around a black hole where the required escape velocity surpasses the speed of light, making escape impossible. Thus, any object, including light, that crosses this threshold is trapped indefinitely. Black holes are invisible in space because they emit no light; however, they can be detected indirectly. Astronomers are able to observe black holes by studying the light from nearby matter that hasn’t yet crossed the event horizon.

Accretion Disk

The main light source from a black hole is a structure called an accretion disk. Black holes grow by consuming matter, a process scientists call accretion, and by merging with other black holes. A stellar-mass black hole paired with a star may pull gas from it, and a supermassive black hole does the same from stars that stray too close. The gas settles into a hot, bright, rapidly spinning disk. Matter gradually works its way from the outer part of the disk to its inner edge, where it falls into the event horizon. Isolated black holes that have consumed the matter surrounding them do not possess an accretion disk and can be very difficult to find and study.

If we could see it up close, we’d find that the accretion disk has a funny shape when viewed from most angles. This is because the black hole’s gravitational field warps space-time, the fabric of the universe, and light must follow this distorted path. Astronomers call this process gravitational lensing. Light coming to us from the top of the disk behind the black hole appears to form into a hump above it. Light from beneath the far side of the disk takes a different path, creating another hump below. The humps’ sizes and shapes change as we view them from different angles, and we see no humps at all when seeing the disk exactly face-on.

Event Horizon Shadow

The event horizon captures any light passing through it, and the distorted space-time around it causes light to be redirected through gravitational lensing. These two effects produce a dark zone that astronomers refer to as the event horizon shadow, which is roughly twice as big as the black hole’s actual surface.

Photon Sphere

From every viewing angle, thin rings of light appear at the edge of the black hole shadow. These rings are really multiple, highly distorted images of the accretion disk. Here, light from the disk actually orbits the black hole multiple times before escaping to us. Rings closer to the black hole become thinner and fainter.

Doppler Beaming

Viewed from most angles, one side of the accretion disk appears brighter than the other. Near the black hole, the disk spins so fast that an effect of Einstein’s theory of relativity becomes apparent. Light streaming from the part of the disk spinning toward us becomes brighter and bluer, while light from the side the disk rotating away from us becomes dimmer and redder. This is the optical equivalent of an everyday acoustic phenomenon, where the pitch and volume of a sound – such as a siren – rise and fall as the source approaches and passes by. The black hole’s particle jets show off this effect even more dramatically.

Corona

It’s been called one of the most extreme physical environments in the universe. Strong magnetic fields threading the inner accretion disk extend out of it, creating a tenuous, turbulent, billion-degree cloud. Particles in the corona orbit the black hole at velocities approaching the speed of light. It’s a source of X-rays with much higher energies than those emanating from the accretion disk, but astronomers are still trying to figure out its extent, shape, and other characteristics.

Particle Jets

In black holes of all sizes, something strange can occur near the inner edge of the accretion disk. A small amount of material heading toward the black hole may suddenly become rerouted into a pair of jets that blast away from it in opposite directions. These jets fire out particles at close to the speed of light, but astronomers don’t fully understand how they work. The jets from supermassive black holes – the type found in the centers of most big galaxies – can reach lengths of hundreds of thousands of light-years. In cases where the jets happen to angle into our line of sight, we may only easily detect the one firing toward us due to Doppler beaming. This process makes the near jet considerably brighter, but greatly dims the rear jet.

Singularity

General relativity predicts that the very center of a black hole contains a point where matter is crushed to infinite density. It’s the final destination for anything falling into the event horizon. The singularity may be either a physical structure or a purely mathematical one, but right now astronomers don’t know which is true. The prediction of a singularity may signal the limits of relativity, where quantum effects not included in the theory become important in a more complete description of gravity.