Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

UK public sector borrowing increased in September and was higher than official forecasts, underlining the scale of the challenges facing chancellor Rachel Reeves as she prepares to raise taxes in next week’s Budget.

Borrowing — the difference between public sector spending and income — was £16.6bn in September, £2.1bn more than in the same month last year and the third-highest September figure since monthly records began in January 1993, the Office for National Statistics said on Tuesday.

The figure was lower than the £17.5bn expected by economists polled by Reuters but above the £15.1bn forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility, the UK watchdog.

In the first six months of the fiscal year to September, borrowing was £79.6bn, which was £1.2bn more than in the same period in the last financial year and higher than the £73bn forecast in March by the OBR, highlighting the challenging fiscal position ahead of the Budget on October 30.

ONS deputy director for public sector finances Jessica Barnaby said: “Borrowing this month was about £2bn up on last year, making this the third-highest September figure on record. While tax revenue increased, this was outweighed by increased spending, partly due to higher debt interest and public sector pay rises.”

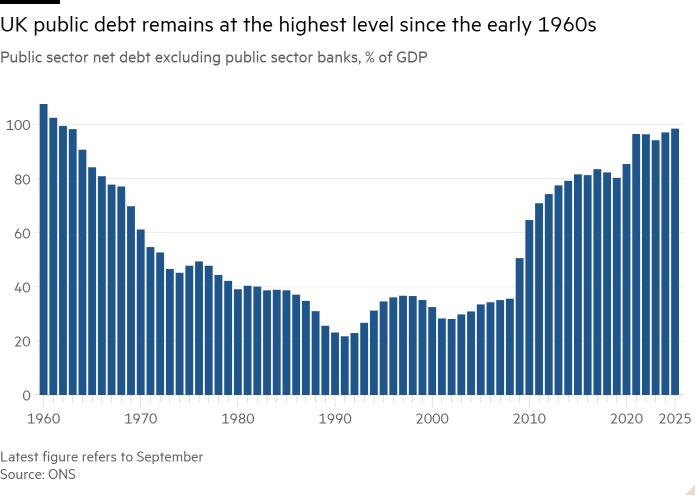

Public sector net debt, or borrowing accumulated over time, was 98.5 per cent of GDP at the end of September, the highest level seen since the early 1960s, the ONS said.

Reeves has identified a £40bn funding gap, most of which is likely to be filled by tax rises. She has ruled out increases to income tax, VAT and national insurance for employees, but she is expected to increase capital gains and inheritance taxes as well as extend the income tax threshold freeze beyond 2028.

Not adjusting the tax thresholds for the impact of inflation pushes people into higher tax brackets as they receive pay increases — a phenomenon known as “fiscal drag” — and increases government revenues.

The chancellor has also signalled higher capital spending aimed at boosting economic growth. This could be aided by tweaks to one of the government’s fiscal rules, which pledges to reduce public debt as a share of GDP between the fourth and fifth years of the forecast.

The other self-imposed fiscal rule involves balancing the current budget, which excludes investment, during the forecast period, which will end in 2029-30.