This article is an on-site version of our Europe Express newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday and Saturday morning. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning. The result of Moldova’s EU membership referendum is on a knife’s edge this morning, with the result set to hinge on the last few thousand votes counted. And President Maia Sandu’s re-election bid will face a gruelling second-round run-off against her pro-Russian rival in a fortnight.

Today, our Rome bureau chief reports on Giorgia Meloni’s efforts to rescue her Albania migration scheme after it was shot down by the courts, and our energy correspondent reveals what’s undermining a technology many hoped would be a silver bullet for Europe’s green revolution.

Rescue mission

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni is scrambling to salvage her controversial scheme to hold irregular migrants in offshore centres in Albania, after an Italian court ordered the first group of migrants dispatched there to be transported immediately to Italy, writes Amy Kazmin.

Context: Meloni came to power promising tough measures to stem the influx of irregular migrants from across the Mediterranean, but has struggled to fulfil that pledge. She had touted the Albanian scheme as an innovative model the rest of the EU could follow.

Meloni and Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama agreed last summer that Italy could operate two centres in Albania with a total capacity of 3,000 healthy, male migrants per month from countries deemed “safe”, while their asylum requests were processed.

The centres formally opened last week, when Italian coastguard officials delivered 16 migrants from Bangladesh and Egypt — two of the 22 countries Rome has designated safe for migrant returns, with some specific exceptions.

Of those first arrivals, four were sent on to Italy immediately: two on suspicion of being minors, and two for medical reasons. On Friday, Rome’s immigration court ordered the remaining dozen to follow suit, citing a European Court of Justice ruling that countries could not be “partially safe”.

Italy’s opposition parties — highly critical of a deal they consider little more than a political theatre — are up in arms over an estimated €60mn spent on the centres and supporting infrastructure so far this year.

At a cabinet meeting today, Meloni’s government will try to strengthen the legal foundation of designating countries safe for migrant returns, in a bid to ensure the transport of future groups of migrants withstands judicial scrutiny.

The legal wrangling is not just pertinent to Meloni, whose core electorate is closely watching. Many other EU leaders have endorsed her Albania model or intimated they would be keen to try something similar.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said last week that Brussels would “draw lessons” from the scheme as it “explore[s] possible ways forward as regards the idea of developing return hubs outside the EU”.

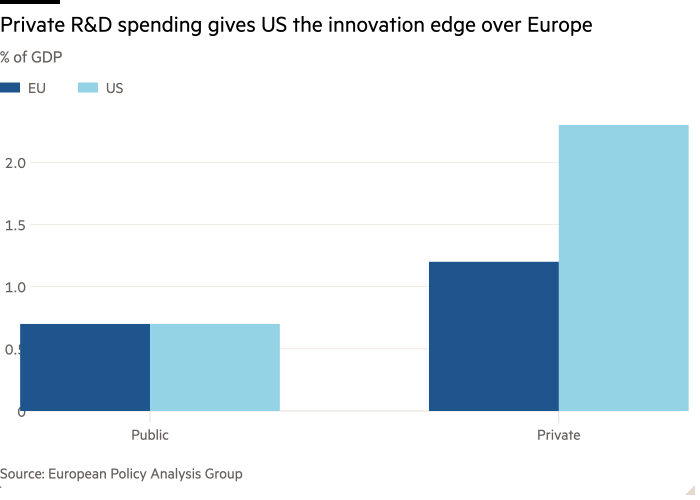

Chart du jour: Innovation race

If Europe wants to take a digital leap across its innovation gap, it should focus less on state handouts and instead push the private sector to do more, writes Martin Sandbu.

Hot air

Heat pump policies in nine EU countries are “deeply flawed”, according to a new study assessing the lagging take-up of a technology seen as critical to cutting emissions from household heating, writes Alice Hancock.

Context: Heat pumps work in a similar way to air conditioning but in reverse. When powered by renewable energy they are seen as a way to decarbonise heating in buildings, which accounts for 35 per cent of the bloc’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The EU aims to fully decarbonise its building stock by 2050. To do that it will need at least 60mn heat pumps by 2030 but will fall 17mn short, according to the European Heat Pump Association’s estimates.

After a bump following the energy crisis, sales of heat pumps, a clean technology of which Europe can claim leadership, have started to lag.

The reason? Few countries have established “robust” policy frameworks, according to a report from the Polish think-tank Reform Institute.

Out of the 10 largest heat pump markets in Europe surveyed, Reform Institute found that nine — including UK, France, Spain and Germany — have “deeply flawed” policies to incentivise take-up.

Among the problems: delays to subsidy payments, a lack of loans to pay for costs not covered by grants, and poor outreach to vulnerable households.

The stakes for encouraging the heat pump sector are high: it employs 170,000 people in Europe.

French socialist MEP Thomas Pellerin-Carlin said that heat pumps were “central” to the EU’s energy transition.

“[They] can help free us from our dependence on Vladimir Putin’s gas, and lower energy bills for European families and businesses. But here lies the paradox: despite its pivotal role in Europe’s energy security, the heat pump industry is now struggling,” he added. “This downward trend is the direct result of poor policy decisions at both EU and national levels.”

What to watch today

-

European parliament president Roberta Metsola opens the chamber’s plenary session and meets with Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission.

-

EU agriculture and fishery ministers meet in Luxembourg.

Now read these

Recommended newsletters for you

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: [email protected]. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe