Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Promising to tackle red tape is a popular British pastime. Sir Keir Starmer is also partial. The prime minister told global business leaders this week he would “rip up” growth-blocking bureaucracy as he urged them to invest in the UK.

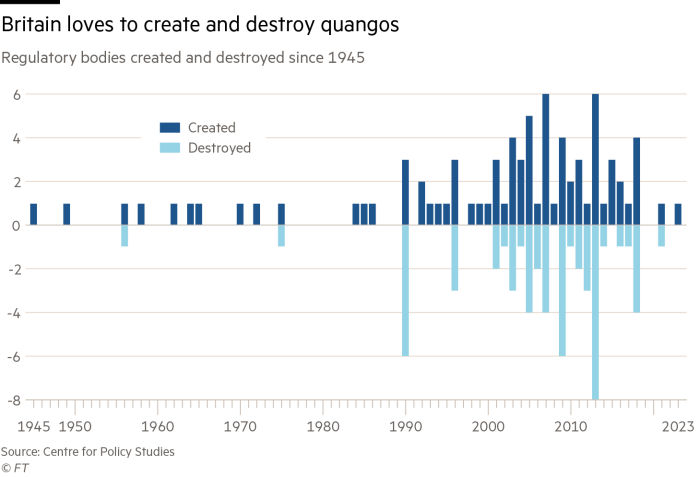

UK governments have repeatedly promised similar things: David Cameron was very fond of quango and red tape “bonfires”. Such promises came up short. A total of £35bn of gross annual regulatory costs were imposed between 2010 and 2019 alone (in 2023 money), estimates the Centre for Policy Studies. Bureaucracy still ranks highly among investors’ biggest bugbears. Starmer could learn something from past failed efforts.

There has generally been a temptation to accompany red tape-slashing pledges with grand targets. The 2011 “one in one out” rule for new regulations became “one in two out” and then “one in three out”. These became bureaucratic exercises in themselves, with departments searching for scrappable regulation for when new rules were needed.

Reducing regulatory burdens should not be a numbers game. A small minority of regulations typically generate the vast majority of regulatory costs, according to a 2023 Social Market Foundation report.

Indeed, often the real problem is speed and process, rather than regulation itself. The East Anglia 2 wind farm, a near 1 gigawatt project some 33km from the Suffolk coast, is a good case study.

Developer ScottishPower was awarded the seabed rights to build turbines in that part of the southern north sea towards the end of Gordon Brown’s premiership. Yet it has taken 14 or so years for the Spanish-owned group to reach a position where it can start awarding contracts to suppliers and begin construction.

This was, in part, a failure to think ahead. Over a decade into the process, concerns were raised over the impact of turbines on local bird populations. Such issues should be settled long before any rights are awarded.

EA2 was also delayed by a judicial review after local communities complained about the design and location of onshore grid infrastructure. Again, those issues might be resolved with a wider upfront plan looking at the region’s possible infrastructure and how it could be best built. Communication is another basic flaw, with regulators accused of being difficult to reach or opaque to deal with.

Some of Starmer’s initiatives offer promise such as the (albeit bizarrely named) “mission control” group, which aims to root out problems early to build energy infrastructure faster. But the British fixation on the volume of red tape will not be easily quashed — and that approach has repeatedly failed to deliver anything approaching meaningful change.